I don’t like straying into Geo-political analysis on this site, so I’ve posted a piece on Syria here

I don’t like straying into Geo-political analysis on this site, so I’ve posted a piece on Syria here

The conviction of a team of radical would-be terrorists who discussed planting IEDs in the lavatories of the British Stock Exchange reminds me that lavatories are a theme in many IED attacks, which I think is curious. Here’s a range of previous “bombs in the bogs””

Only a couple of days ago some sort of apparent explosive device was found in the lavatory of a Libyan plane in Egypt For what its worth I don’t think it was an IED but the story is pretty cloudy for now.

In May 2008 there was the very peculiar incident in Exeter, UK, where a decidedly odd individual detonated a device while he was in the lavatories of a fast food restaurant.

In 1957 an elderly man blew himself up in the lavatory of a passenger aircraft over California. A good investigation report is here The device was constructed by dynamite and blasting caps with the blasting caps initiated by matches and burning paper. Only the perpetrator was killed.

A similar dynamite IED functioned in the lavatory of an aircraft in 1962 over Iowa, this time killing all aboard. http://www.airsafe.com/plane-crash/western-airlines-flight-39-1957.pdf

A Canadian passenger aircraft blew up after a device exploded in the lavatory over British Colombia in 1965. The crime was never solved.

In 1939, as part of a significant Irish terrorist bombing campaign in England a bomb was planted in a public lavatory in Oxford street. Disaster was averted when the lavatory attendant dumped the IED in a bucket of water (not a good response, but a brave man). Several other incidents in this campaign were IEDs left in lavatories. The attendant was awarded £5 for his bravery

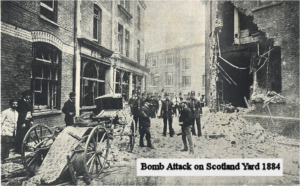

In 1884, during another Irish bombing campaign in England, (yes there have been a few) the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, Scotland Yard, was severely damaged in an explosion caused by a large IED being left in a public lavatory next door to the police Headquarters. Here’s a picture.

There’s an interesting aspect to this story. Several months earlier, in 1883, an Irish revolutionary organization , the Irish Republican Brotherhood sent a letter to Scotland Yard threatening to ‘blow Superintendent Williamson off his stool’ and dynamite all the public buildings in London on 30 May 1884. The Met Police largely ignored the warning, and then on the very day promised the explosion at Scotland Yard occurred, as did two other explosions elsewhere in London. The failure of the Met Police to protect their own headquarters, as well as the occurrence of several other IED attacks across London embarrassed the police severely and led indirectly to the formation of Special Branch.

There are numerous other IED attacks on lavatories, too many to list.

Around about 1751, Benjamin Franklin became the first person to initiate explosives with electricity. Franklin, as usual, was well ahead of other scientists around the world. While one aspect of this research leads us to modern electrical initiation of explosives and munitions another leads us towards the hazards of lightning when associated with stored munitions, and Franklin became expert at lightning conductors for munition stores.

For the past few years I’ve been mentally filing interesting accidental explosions from history and I’m now being encouraged to gather my notes together, and indeed relay some of the intriguing aspects to these stories. Shortly you’ll see a new page on this blog dedicated to such events.

Here’s a great example:

In August 1769 lightning struck the tower of the Church of San Nazaro on Brescia, Italy. In the vaults of the church over 200,000 pounds of explosive was stored. The resulting explosion killed 3000 people and destroyed a large part of the city.

For many centuries gunpowder was stored in churches – there seems to have been a belief that the church bells prevented lightning. Unfortunately I guess the opposite is true – the tall steeples and towers on a church actually encourage lightning strikes. During thunder storms teams of men rang the bells in church towers in efforts to prevent thunderstorms. During the period 1753 to 1786 lightning killed 103 French bell ringers. A triumph of belief over evidence surely.

Interestingly Franklin was extremely active in advising European governments after the Brescia event on the principles of lightning protection for munitions stores. At one stage there was a dispute over the best shaped lightning rods , with Franklin a proponent of sharp pointed rods on top of buildings and an Englishman, Benjamin Wilson urging the use of ball shaped terminals below the roof line. The argument became political, and George III decided he didn’t want American advice…. And Franklin’s conductors were replaced on several British munitions stores. One of them in Sumatra subsequently disappeared with a bang during a thunderstorm.

As late as 1856 gunpowder stored in a church in Rhodes was hit by lightning and it exploded killing , allegedly, 4000 people.

This history of looking at IEDs and IED incidents for technical intelligence is interesting and goes back quite a way – certainly as far as the late 1500’s when Elizabethan spy master Francis Walsingham engaged Giambelli, the IED maker who made the Hellburner hoop – (Walsingham calls him “Jenibell” but there is no doubting it is the same person)

Stories of the British WTI investigations of Russian sea mine IEDs are here, and I have a stack of stuff on Colonel Majendie’s quite excellent WIT reports from the 1880s to discuss in future blogs. For now though, here’s a very early US WIT report from 1860, by Major Richard Delafield. He is reporting on a Russian IED encountered by the British four years earlier in 1856.

As the British and French fought the Russians in Crimea, there was significant interest in the US military about how warfare was developing given the technological advances in weapons and tactics used by both sides in the Crimea. In 1855 Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, created a team called “The Military Commission to the Theater of War in Europe”. The team consisted of three officers – Major Richard Delafield, (engineering), Major Alfred Mordecai (ordnance) and Captain George B McClellan of later civil war fame. McClellan resigned in 1857 and the report was published in 1860. It is wonderfully detailed and I’d recommend it to any students of military history – it covers just about all aspects of European military developments, from defensive positions, artillery to mobile automated bakeries aboard ship, ambulance design, hospital design and French military cooking techniques.

In the Crimean War the Russians protected their elaborately engineered defences with “fougasse” explosive charges – nothing new there, because as a tactic this is as old as gunpowder itself. Until the Crimea these fougasses had to be initiated by an observer, i.e. command detonated by burning fuze or the newly invented concept of electrical initiation. However the Russians had a new technique to deploy. Immanuel Nobel (father of Alfred Nobel) had been engaged by a Russian military engineer, Professor Jacobi to develop submarine charges and a contact fuzing system. These “Jacobi” fuzes consisted of a pencil sized glass tube filled with sulphuric acid fastened over a chemical mix. Some reference history books say the chemical mix was potassium and sugar but I think that’s probably a misunderstanding – I would suspect the mix was actually either potassium permanganate and sugar or potassium chlorate and sugar, as in Delafield’s report below. This explodes initiating a gunpowder charge sealed in a zinc box. One might have expected Mordecai to take an interest in the IEDs but it was Delafield who took particular interest and heartily recommended the use of such things by the US military. Here is an extract from Delafield’s “WIT” report from the device recovered to the British “CEXC:”:

They consisted of a box of powder eight inches cube (a), contained within another box, leaving a space of two inches between the, filled with pitch, rendering the inner box secure from wet and moisture, when buried under ground. The top of the exterior box was placed about eight inches below the surface, and upon it rested a piece of board of six inches wide, twelve inches long and one inch thick, resting on four legs of thin sheet iron (o), apparently pieces of old hoops, about four inches long. The top of this piece of board was near the surface of the earth covered slightly, so as not to be perceived. On any slight pressure upon the board, such as a man treading upon it, the thin iron supports yielded. When the board came into contact with a glass tube (n) containing sulphuric acid, breaking it and liberating the acid, which diffused within the box, coming into contact with chloride of potassa (sic) , causing instant combustion and as a consequence explosion of the powder.

Delafield goes on to note that the British and French exploiting these devices did not have a chemistry lab available to properly identify the explosives.

A second device is then described:

Another arrangement, found at Sebastopol, was by placing the acid within a glass tube of the succeeding dimensions and form. This glass was placed within a tin tube, as in the following figure, which rested upon the powder box, on its two supports, a, b, at the ends. The tin tube opens downwards into the powder box, with a branch (e) somewhat longer than the supports, (a, b) This , as in the case of the preceding arrangement, was buried in the ground, leaving the tin tube so near the surface that a man’s foot, or other disturbing cause, bending it, would break the glass within, liberating the acid, which, escaping through the opening of the tin into the box, came into contact with the potassa, or whatever may have been the priming, and by its combustion instantly exploded the powder in the box. What I call a tin tube, I incline to believe, was some more ductile metal, that would bend without breaking. For this information I am indebted to the kindness of an English artillery officer who loaned me one in his possession and from which measurements were made.

This last sentence has the hairs on the back of my neck standing up – because I know that the famous Colonel Majendie, who later became the British Chief Inspector of Explosives and who conducted remarkable IED and WIT investigations some 30 years later, fought as a young artillery officer at Sebastopol. Could it be the same man? I’d like to think so.

Later in the report is some intriguing details of electrical initiators for explosives, including the use (in 1854 )of mercury fulminate.

I’m also on the hunt for a report I know exists of a US investigation into Chinese Command initiated river mine IEDs from the Boxer rebellion in 1900. When I get it I’ll post details.

…..in 1840.

A post a couple of months ago gave details of the development of IEDs by Confederate officer Brigadier General Gabriel Raines in the American Civil War. I’ve now found a record of the same officer using IEDs even earlier, in the Second Seminole Indian War in Florida in 1840. Here’s the story:

In 1839 Raines was posted as a company commander in north central Florida. In May 1840 he became commander of a single unit holding Fort King as other forces responded to (insurgent) activity at other Forts (FOBs). The insurgent forces seeing Fort King undermanned started to exploit the situation and killed two soldiers within sight of the Fort. Raines wanted to seize the initiative and deter such attacks so developed an IED, a buried shell, covered with military clothing, designed to function if the clothing was picked up on a simple pull mechanism. After several days waiting the IED exploded and Raines, with 18 men, went to the explosion site, but found “naught but a dead opossum”. However while investigating his own IED he was attacked by a group of 100 Taliban Seminoles. Although they were fought off, Raines suffered serious injury, and was not expected to survive. Even his obituary was published in a newspaper. However he recovered, was promoted, and commended for “Gallant and Courageous service”. He went on to place a second IED but later had to remove if because his own soldiers were scared of it. Raines’s actions were not approved by many in the US military. 20 years later when he used IEDs against the Union, his “dastardly business” was again condemned by Union Brigadier General William Berry who had not forgotten Raines’ exploits in Florida.

Raines died in 1881 of medical conditions associated with his injuries sustained in 1840.