This is just a follow up to my last post. I’ve been searching for more details of Emmet’s rockets and other IEDs in Dublin in 1803 . The more I read about Emmet’s uprising the more I see strong similarities between the current Syrian revolution and Dublin.

To get the current context, have a trawl through the “Brown Moses” blog here :

Note the current context of home made rockets and “DIY” IEDs being produced in workshops. Now, Dublin of 1803 wasn’t all that different:

- Rebels were inspired by revolutions taking place elsewhere. In Ireland it was the American revolution and the French revolution that inspired a group of Irish nationalists. Today the Syrian rebels are inspired by the other Arab spring revolutions.

- Emmet established five improvised munition workshops across Dublin. My instinct tells me that these looked very similar to some of the workshops seen producing improvised weaponry in Aleppo. In Syria, here’s a range of home made weapons and IEDs

- In Dublin Emmet produced the IEDs and munitions with a team of 40 people across his five Dublin workshops. Interestingly the workshops were well disguised behind false walls. I described the IEDs in my last post, below.

I’ve been trying to find more details of the design of rockets developed by Emmet. Rockets had become something of a flavour at the time – The French had been using rockets on the battlefield for the previous few decades, but with limited effect. Then in the Mysore wars in India the British found themselves attacked by effective rockets with explosive warheads, to their great consternation.

The British captured a number of Mysorean rockets in 1799 and examined them (another example of early technical intelligence activities). Emmet would have been aware of their impact on the British military.

As mentioned in the earlier post Emmet met the American Robert Fulton in Paris at about this time, and Fulton too had expertise in rocketry which he may have passed on.

The key development here, which the Mysore rockets utilized, was to use a metal case for the rocket body. Until then the bodies where generally paste board (as in modern fireworks). A pasteboard body limits the internal pressure possible and therefore the size and range fo the rocket. But much higher internal pressures are possible with metal bodies. Both the Mysore rockets, Emmet’s rockets and the very slightly later British Congreve rockets all used a metal body.

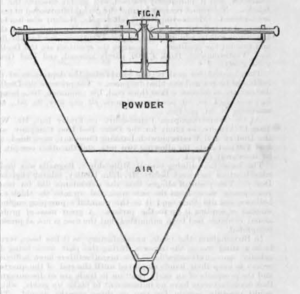

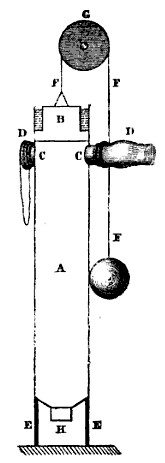

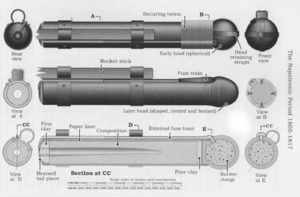

How much the British Congreve Rocket system was influenced by Emmet’s rocket designs is unclear – but very interestingly there is a report that one of Emmet’s assistants, a Mr Pat Finerty, subsequently went to work at Woolwich where Congreve’s rockets were under development after the events in Dublin. Congreve’s rocket was described as an improvement on, but similar in design to Emmet’s. Here’s a diagram of an early Congreve rocket, which is therefore likely to have been broadly similar to Emmet’s rockets.

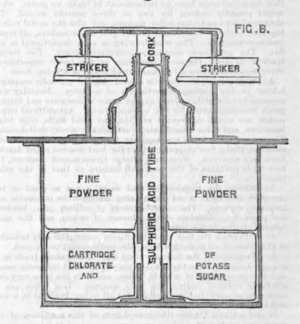

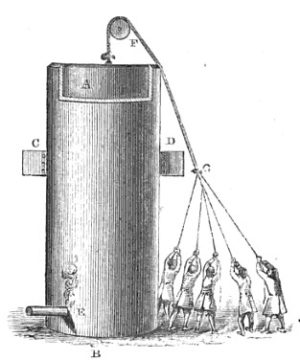

Note that there is a warhead at the front, and the warhead at the front is initiated by a burning fuze running the length of the outside of the rocket body. The rocket motor and the warhead fuse would have been lit simultaneously. The stabilising “stick” is not shown in this diagram. Congreve rockets would have been initiated by a flintlock mechanism, but Emmets probably with a simpler burning fuze. Here’s a picture of a Congreve flintlock mechanism. the string is a lanyard to the release spring , I think which releases the cock hammer.

Emmet’s rockets were intended to be deployed to be fired at cavalry, and also as signal rockets – I’m not sure if that entirely makes sense, given the fuzing mechanism – they would make much more effective indirect fire area weapons, perhaps fired into British garrisons. Nonetheless horizontally fired munitions (although not technically rockets) aimed at the British Military were being used by Irish terrorists some 200 years later. As such I think Emmet’s rockets have an important place in history. I also think that although they had been used on the battlefield before, this was the first use of such technology by freedom fighters/ terrorists.

The truth is however that Emmet’s revolution was nothing short of a shambles, and the rockets and the explosives beams and the grenade IEDs barely got used, if at all. Emmet’s purported notes after the failed uprising gives a frank and candid account:

- Emmet describes his detailed plan for the deployment of pikemen, “beam” IEDs and rockets across Dublin, in detail. He describes the plan for deploying caltrops and anti-cavalry boards with nails in them, chains across streets, deployment of grenades and stones to throw, and muskets. But the deployment never actually occurred, because the United Irishman expected to man the positions, from Kildare and Wicklow failed to arrive. There was evidence of confusion and poor communication between the revolutionary elements, and possible the spreading by British agents of incorrect information. Emmet expected several thousand rebels supporting him, but eventually had less than a hundred, and even these he couldn’t control, a good proportion of then being “with drink”.

- Due to a lack of funds, scarcely any of the expected blunderbusses were bought

- The man designated as being responsible for preparing the fuzes for the “exploding beam” IEDs “forgot” to prepare them and went on an errand to Kildare.

- An accidental explosion at one of the IED workshops prevented much of the material being stored there being available.

- The slow matches used to initiate grenades and beam IEDs were prepared incorrectly and would not function.

- The same person responsible for the slow matches then “lost” the grenade fuzes.

- Other material such as scaling ladders and irons to chain up streets were not prepared in time.

- Emmet describes the eventual disaster as “a failure in plan, preparation and men”

There is a strong suspicion that some of the failures were “helped along “ by British agents.

In a future post I’ll look at the evolutions of Congreve’s and later rockets. Nowadays rockets are almost invariably fin stabilized – have a look at this one spotted recently by Brown Moses – but for some time the “stick method” was used by Congreve and subsequent rocket designs and of course remains in modern fireworks.

I find it fascinating that rockets have returned to the revolutionaries arsenal.