Follow this link here, to a post I have put on another site, but which readers of this blog with an EOD or ECM background I think will find interesting.

Follow this link here, to a post I have put on another site, but which readers of this blog with an EOD or ECM background I think will find interesting.

There’s been discussion on the letters pages of “The Times” about the origins of the “Tommy Atkins” reference – the standard typical British soldier with all the phlegmatic character so well described by Kipling. Well, it turns out that Kipling didn’t “invent” the name out of the blue, and the history of Tommy Atkins as a real person is moving, dramatic and a little older.

In 1843, The Duke of Wellington, a national hero, former Prime Minister and Victor of Waterloo was a “Minister without Portfolio”. He was an elderly man of 73 and the Grand Old Man of the British establishment. The previous year he had been re-appointed as Commander in Chief of the Army.

The Duke of Wellington, aged 74

Officers on the Army Staff came to show him a new piece of bureaucracy – a form that soldiers had to sign to claim their allowances. They wanted to create a “typical entry” as a guide for soldiers entering their details. The discussion turned to the name that the guide should use as its example, and they asked the old General his opinion.

Wellington sat back and thought. He recalled one of his earlier campaigns, in the Low Countries in 1793. After a battle he had come across a gravely wounded solider, lying on the ground. That soldier had served in the Grenadiers for 20 years, could neither read nor write, but was the “best Man-at-Arms in the Regiment”. His name was Thomas Atkins. Atkins was severely wounded, and had begged the stretcher bearers to leave him be, so that he could die in peace. Looking up and seeing the Duke’s concern, the man uttered his last words. “It’s all right, Sir. It’s all in a day’s work.”

Wellington still remembered that experience, 50 years later, and so the name on the form and for every British soldier since became “Thomas Atkins”.

The press are pretty awful at describing any given terrorist attack as something “new”. I hope this site and the blog posts associated with it show that very often there is nothing new under the sun. Tactics, technology, targets all repeat themselves in one form or another, and history is forgotten time after time. Partly this is because of the “shock” affect of terrorism, which can indeed be stunning, and partly because people (journalists and politicians included) are lazy.

In an effort to counter these, as readers of previous blog posts will have seen, I research and collect early examples of certain kinds of improvised explosive devices, It’s time to summarize a few here, some of which I’ve written about before and otehrs I will write about when time permits.

a. Letter bombs – I have details of letter bombs from 1581 (Poland) and this one from 1764 (Denmark). A Colonel Poulsen, living in Borglum Abbey, received a box through the mail. “When he opens it, therein is to be found gunpowder and a firelock which sets fire unto it, so he became very injured”

b. Vehicle bombs. The Wall St bombing in New York in 1920 is often wrongly cited as the first. There was a famous vehicle bomb in Yildiz, Turkey in 1904 and the attempted assassination of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1800, in Paris using a vehicle bomb. The concept was well known and various designs were circulated in military documentation much earlier. I’ve got some copies of those diagrams.

c. IED shrapnel coated in acid or anti-coagulant. This was trumpeted as a new horrific tactic a few years ago – but the Stern gang attempted such techniques in 1942 (along with exceptionally sophisticated “come-on” tactics) in an assassination attempt on a British Palestinian policeman. The tactical design of this attack is extremely interesting, very thorough, and I’ll post details in a few weeks.

d. Multiple VBIED attacks – attacks in Iraq ten years ago using multiple vehicles against a target such as a hotel were labelled as “new”. But British Army deserters used three trucks to blow up Ben Yehuda St in Jerusalem in 1948, each allegedly containing a ton of TNT and additional material. Their intended target was a hotel. I’m building a full post on this.

Naval EOD and the use of a size LARGE Birmingham screwdriver.

I’m indebted to John C Wideman, author of an excellent and detailed study of US civil war IEDs for information about another ship-borne IED similar to those mentioned in an earlier blog post.

The USS Intrepid was a ketch, originally named the Mastico, captured from Tripoli (now in Libya) in the First Barbary War. The First Barbary War has its origins in interesting parallels with modern piracy.

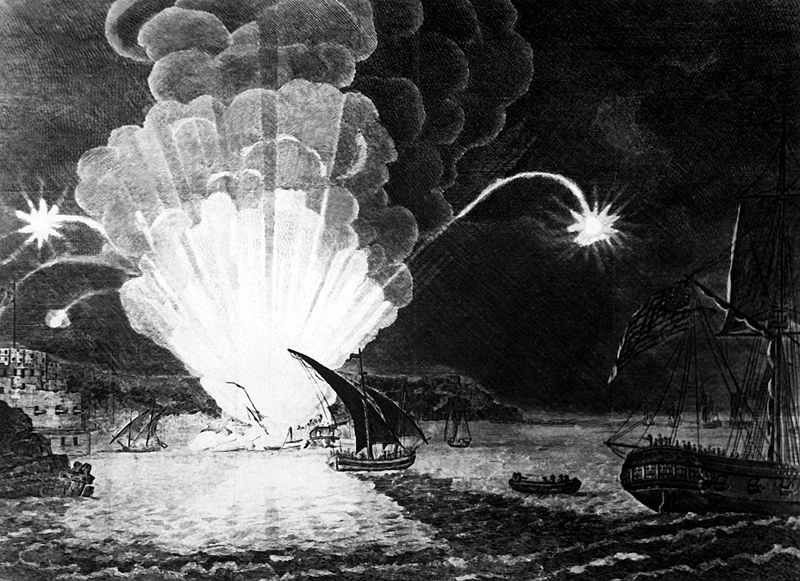

In 1804, the Intrepid was converted into a “floating volcano”, to be sent into Tripoli harbour and blown up amidst the corsair fleet adjacent to the walls of the port’s fortress. The ketch was loaded with 150 artillery shells and 100 barrels of gunpowder. Burning fuzes with a 15 minute delay were attached. a crew of 11, led by Lt Richard Somers manned the vessel. On entering Tripoli harbour, it cane under intense fire, and was unable to manoeuvre towards the intended target. The 15 minute fuze proved unreliable and the ship detonated prematurely, killing the crew who had intended escaping by row boat.

USS Intrepid exploding in Tripoli Harbour

So, it can be seen, the explosively laden ship has been a repeated tactic, since 1584:

1584 – The explosion of the “Hoop”, Antwerp, against the invading Spanish Army. This incident remains, in my opinion the IED that has killed most victims in history, with 800 – 1000 killed. Tell me if I’m wrong.

1693 – The “Vesuvius”, used by the British under Admiral Benbow against St Malo

1694 – The Dieppe Raid, and raids against Dunkirk using the same technique

1804 – The Intrepid used by the American Navy against Tripoli, North Africa

1809 – Two explosive ships used by Admiral Cochrane, against the French, in the Basque Roads. Notably these had 15 minute fuses which exploded prematurely.

1864 – USS Louisiana, used in the US Civil war against Fort Fisher, Wilmington, N Carolina.

1918 – Zeebrugge raid, by the British Navy, using a submarine packed with explosives

1942 – HMS Campbelltown rammed into the dock gates in St Nazaire by the Royal Navy.