For some time now I have been digging slowly and methodically for details of late 19th century techniques for dealing with IEDs, mainly focused on the activities of the London based Colonel Vivian Majendie. As the Chief Inspector of Explosives he had a broad ranging role, including legislation regarding the industrial production and storage of explosives. But Majendie was also responsible for the response to anarchist and Fenian revolutionary IEDs which were remarkably prevalent at the time. Remember that the 1890s, for instance, were referred to as “the decade of the bomb” because of the prevalence of explosive devices.

I have mentioned in previous blogs that Majendie constructed a “secret” facility for rendering safe IEDs. His work there was assisted by Dr August Dupre – a German emigre and highly experienced chemist. This facility was surprisingly just a couple of hundred yards from Downing Street on Duck Island at the bottom end of the lake in St James’s Park, opposite Horseguards.

There is a story that the bomb defusing facility still existed in mothballs in the 1970s. To preserve it, the wooden building and its contents were recovered by the Royal Engineers to Chatham in Kent. The story goes that some RE quartermaster in the 1980s felt it was messing up his stores so it was destroyed and scrapped. Sigh. In such a way is Ozymandias sometimes forgotten.

So for a couple of decades I’ve been interested in what equipment existed there – but Majendie’s OPSEC was pretty good. I think I know where some official files may be that detail it but time has precluded a visit to those archives yet.

But yesterday I turned up a new lead. Firstly I found a document that detailed some of Majendie’s thoughts on EOD operations. He discussed moving suspect devices in wicker hand carts to one of three locations strategically placed around London. One on Duck Island – close to the heart of government in Whitehall and sufficiently remote in its immediate environment. One in the “ditch” surrounding the Tower of London, for IEDs found in the financial centre of London, and one in a cutting or quarry in Hyde Park for devices in the commercial district. It appears that Majendie won approval for the construction of at least two of these (Hyde Park and Duck Island) and that the Duck Island facility was completed first. But not much of a clue as to what it contained, other than some sort of mechanical contrivance for dealing with the infernal machines. So a bit more digging ensued. Now, I know from other research that Majendie conducted close relations with both the United States and with France. Anarchist IEDs were almost endemic in France at the time. Majendie makes some remark in the 1880s that he has “adapted the French techniques” and refers to their approach as often blowing the devices up in place – whereas Majendie prefers to move them to his secret facilities to deal with them there.

But then I find an associated reference that suggests that Majendie used equipment of the same kind for defusing bombs that the French used at the Municipal Laboratory in Paris. A clue, then, and a new avenue.

So, I’ve had some success.

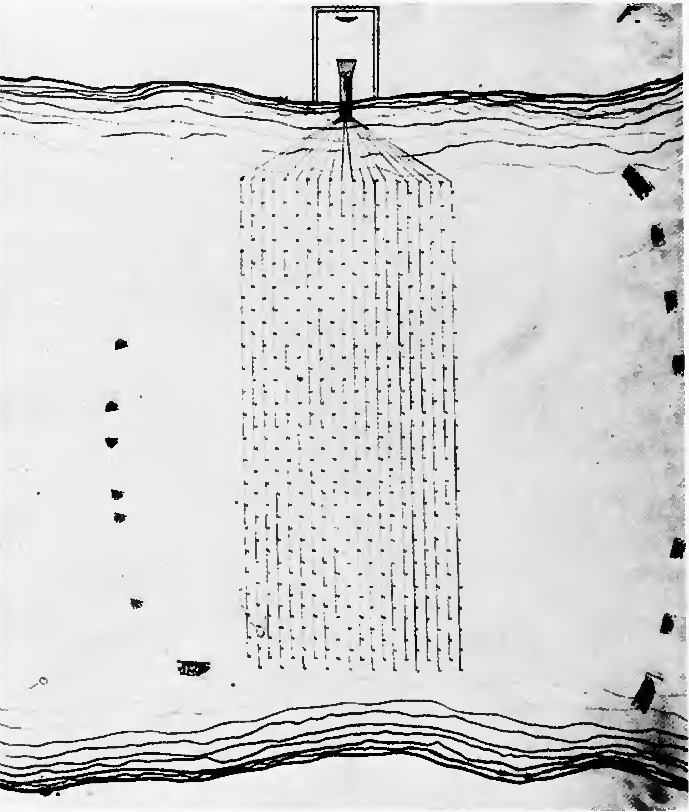

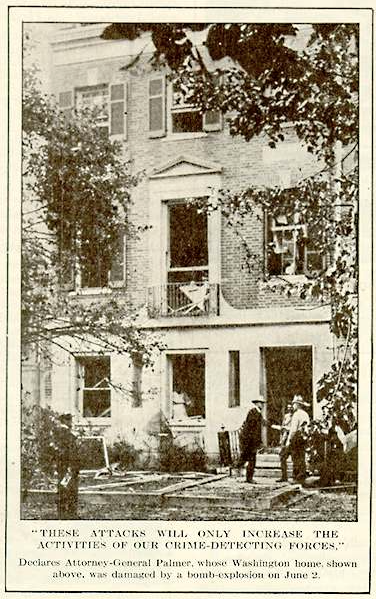

This is a summary of what I have found. The French authorities established a Municipal Laboratory for dealing with IEDs in some open ground near Porte de Vincennes in Paris and others at 3 other locations elsewhere in the City. The facility consisted of some earth banks and a series of wooden huts. I think the facility was set up in the 1880s and certainly was still in existence in 1910. This is an image from 1910.

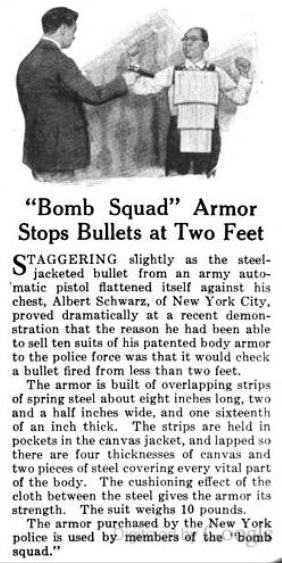

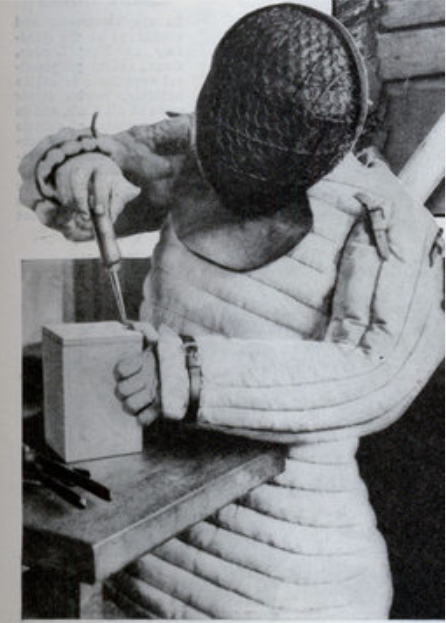

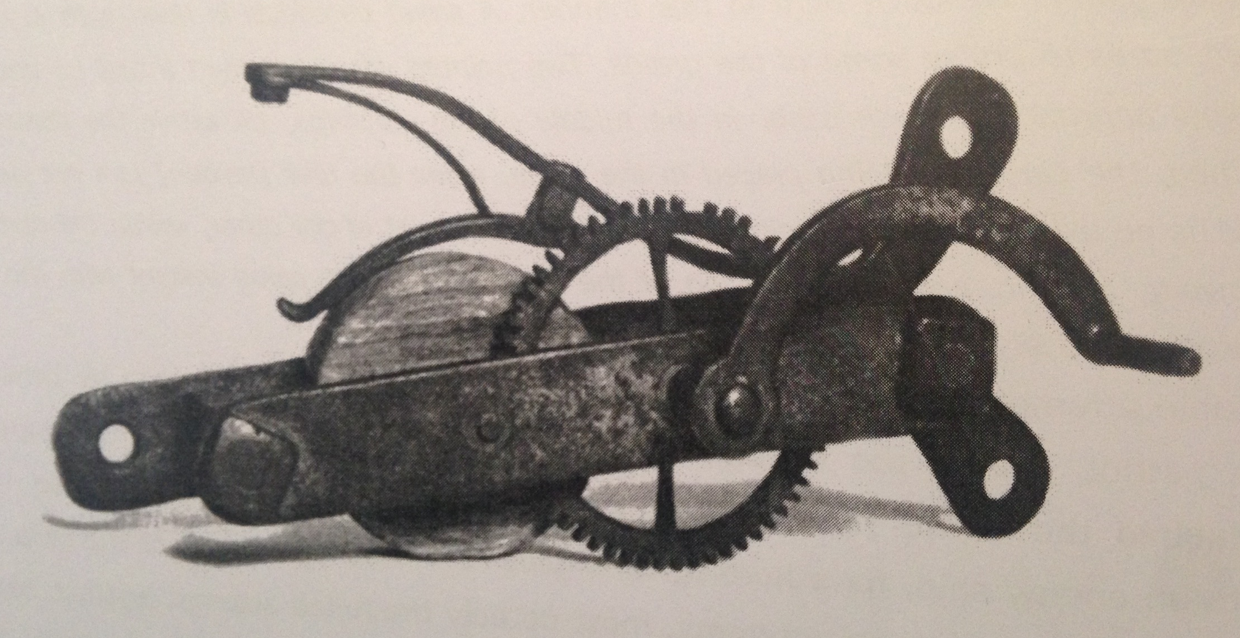

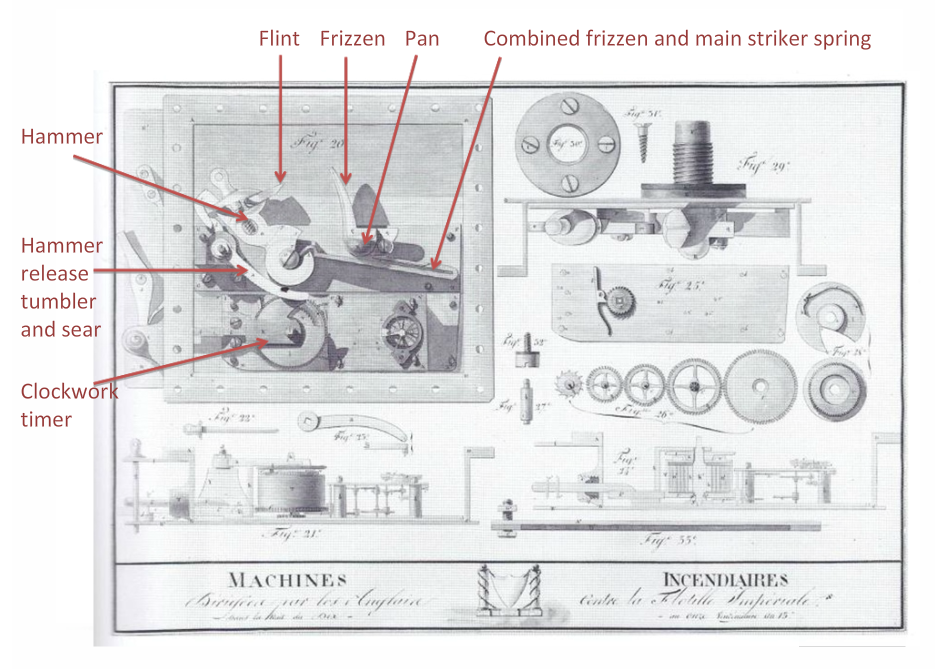

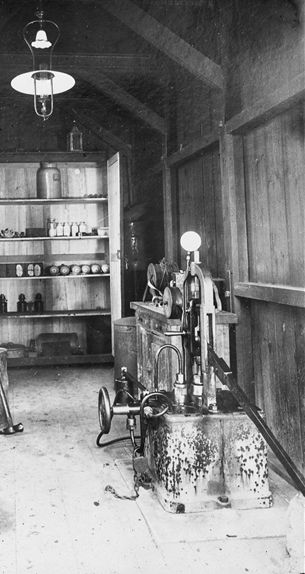

Within this facility was a range of equipment including x-ray equipment (after it was invented) and a very robust piece of machinery called a “Morane Press”. I think this is that key piece of equipment and I have a hunch (nothing more) that Majendie’s facility on Duck Island was somewhat similar in terms of construction, and Majendie too may have used a Morane press. This is a picture of the “Morane press” taken at he the Paris facility, again somewhat later but the press was still in use in 1910.

I then found a beautiful report from 1906 describing the operational routine of the Paris police at the time. The report describes that the occurrence of suspect IEDs in Paris in 1906 was “not at all an infrequent occurrence”. Some elements of the report:

- A “bomb squad’ was based at the laboratory and connected by a telephone to central police headquarters. The headquarters tasked the unit to respond to a suspect IED. The response is described as being similar to a “fire call”.

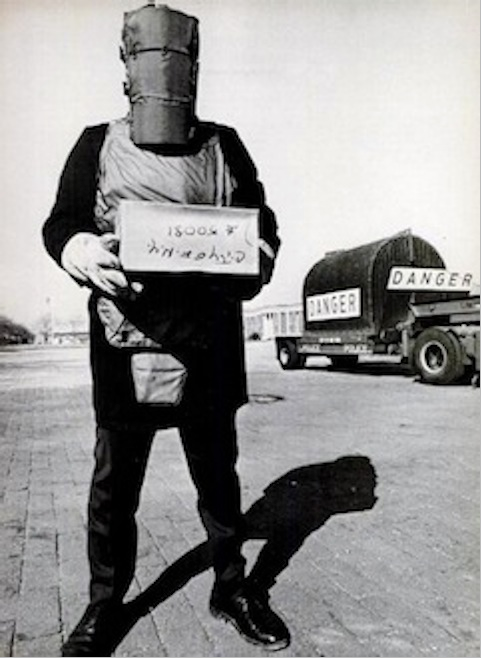

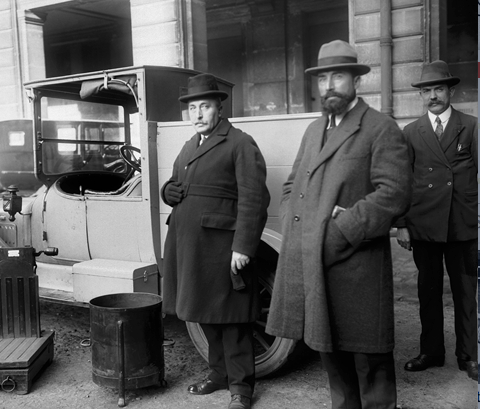

- The lead EOD tech has a fast response vehicle, described as a 16 horsepower “racing bodied” automobile. it is followed by an “automobile bomb van”.

- Six chemists are assigned to the unit, and one always deploys as the lead operator. They work one week shifts, and five weeks off to “recover from nerves”

- The lead chemist brings the “bomb van” close to the device, and the operator after inspecting it, lifts it carefully , maintaining its positional attitude and places it in a containment box. Perhaps their procedures had evolved from the 1880s “blow in place” policy.

The photograph below may show the response vehicle and a containment vessel. I can’t be sure because I think the photo was mislabelled as “Paris police headquarters, 1920s” but I found the photo amongst other photos of the explosive laboratory and to my untrained eye the vehicle looks like a 1906 car not a 1920s car. I think the black object on the floor might be a containment vessel. The operators are certainly steely-eyed.

- The report describes how many IEDs of the time were sensitive to movement which changed its orientation – the initiation mechanism was two liquids which, if the device was tilted, mixed and caused a detonation.

- The bomb van is described a “heavy (voiture lourde) double phaeton 12 hp automobile, refitted from the regular tourist trade, with a pneumatic spring device for gentle running and 120mm tires”

- The “bomb box” or containment vessel is placed over the rear springs, opening by a letdown from behind. It is fitted with shredded wood fibre and into this is placed the IED.

- The IED is then moved accordingly to the facility in Porte de Vincennes or one of three other such facilities strategically placed around the City ( note the similarity to Majendie’s plan) . The concept is to move the device very quickly in case it is time-initiated.

- Once at the facility the device is immediately x-rayed after being placed behind an armoured screen. As noted in earlier posts, the French deployed x-ray equipment for security operations within months of the invention in 1896.

- At this stage, depending on the x-ray, the device may be manually rendered safe. The report mentions a specific IED were the hands of the timing clock could be seen to be stationary from analysis of the radiograph, allowing a manual procedure to make the device safe.

- The report then describes the “hydraulic press”. It is tucked in behind earthen mounds. Here’s a picture of what I think is the pump that powered the Morane press.

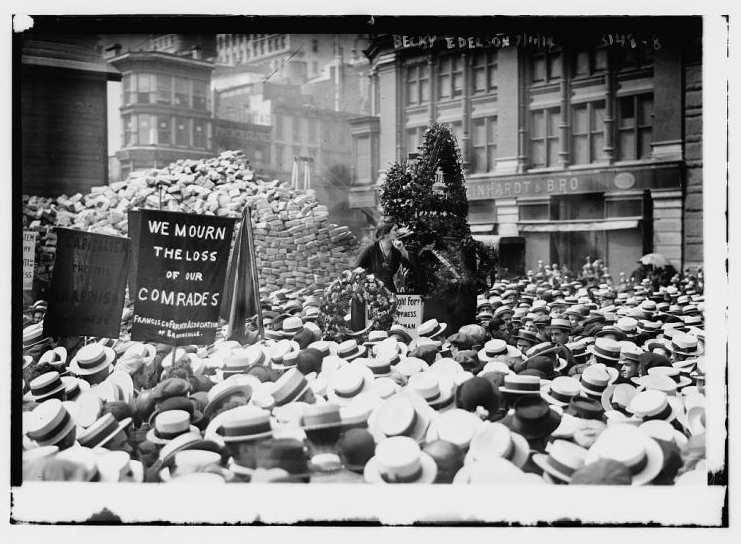

- And here are the earthen mounds surrounding the facility

- The press is used to dismantle IEDs, and if a detonation is caused, the effects are contained. The press is robust enough to survive. Quite often there are detonations several times a week. The effectiveness of the press is described as 75% – three times out of four a device does not explode but the components are recovered for forensic examination. That’s not a bad strike rate at all, given the sensitive explosives used and the initiation types.

- The report also stresses how many of the IEDs are not publicly reported in order to keep the public calm

In summary then I think that the Paris facilities are a remarkable reminder that IEDs are not new, and surges in IED use have been seen before. The facility seems to have been in use for about thirty years, and despite the different techniques of today’s bomb squads, their technology was surprisingly effective. We can’t be certain that Majendie was using the same strategy and same technology in London in the 1890s but I think there is a high degree of likelihood he was. Like today, there was a willingness to share EOD technology, and technical intelligence, between different national agencies. The Paris police clearly had a sophisticated and well resourced EOD unit operating across their city, with a thought-through strategy focused on:

- reducing damage to property

- returning the situation to normality as soon as possible

- technical intelligence and forensically-focused render-safe procedures.