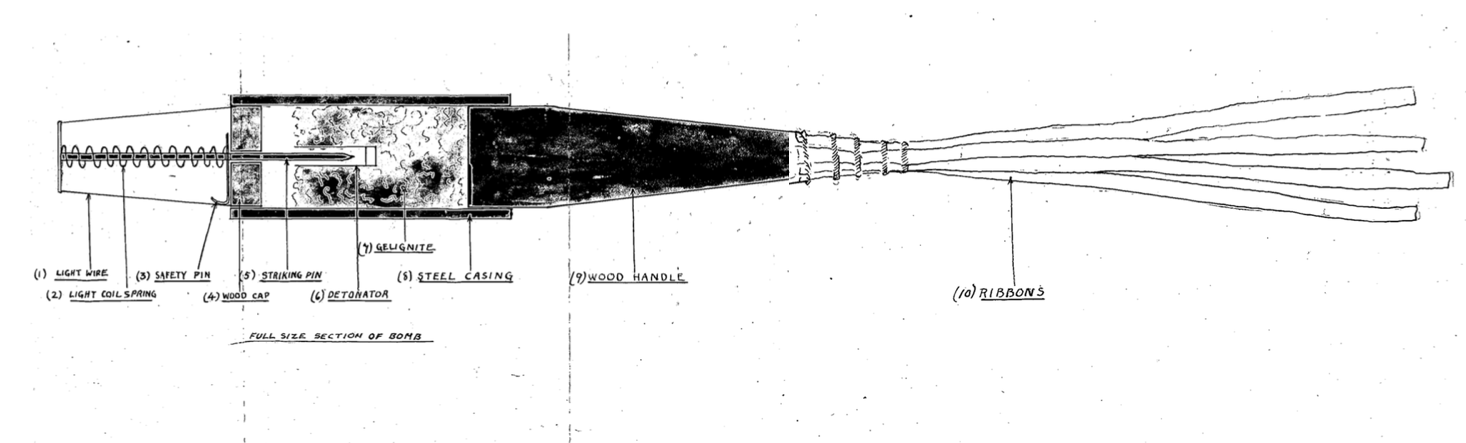

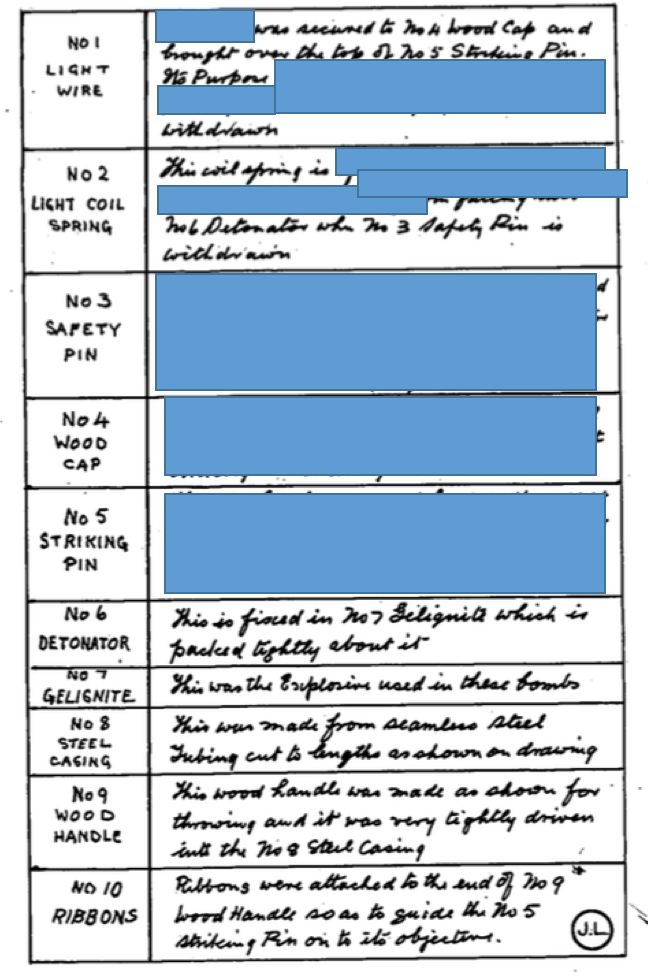

One of the nice things about this blog is that I don’t have to stick rigorously to its stated subject. In the previous post I examined some of the explosive devices used by the Polish Resistance in Warsaw. During that research I came across this story which is simply worth retelling.

The Polish resistance was not without its sense of humour, and the occupying German forces… well lets just say they were German and not renowned for the perspective humour offers. In the heart of Warsaw stood a large statue of the astronomer Copernicus. Copernicus lived when the Kingdom of Poland was part of Prussia so both the Poles and the Germans had claims to him. At the base of the monument was a plaque with the inscription ” To Copernicus, from his countrymen”. The German authorities, on occupying Warsaw, removed the plaque and replaced it with another that read “To the Great German Astronomer”. The statue was in a square right outside a German police station.

One day a group of workmen, seemingly from the city council, arrived and began to work on the base of the statue, unnoticed. They removed the German plaque. It was actually a group led by Polish resistance fighter Maciej Aleksy Dawidowski. It was 10 days before the authorities noticed their plaque had gone missing. The German commander, Governor Fischer was outraged. This is his picture – he looks pretty much like the proto-typical Nazi war criminal that he was doesn’t he?

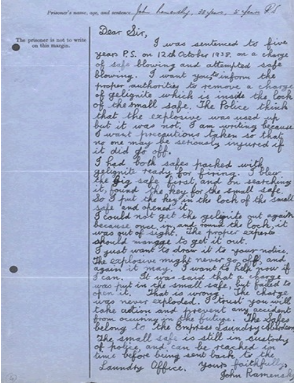

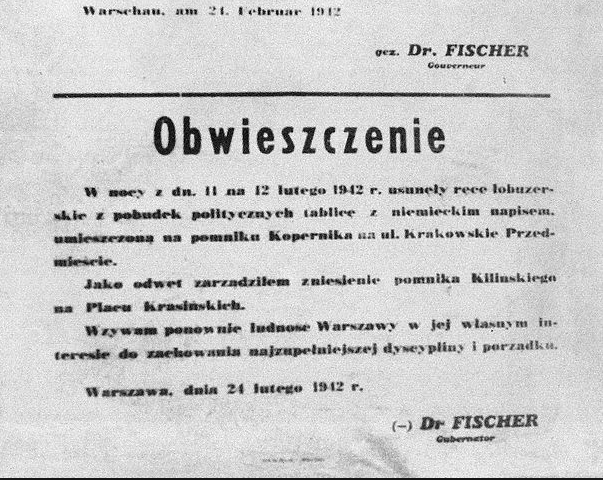

Fischer issued a proclamation below:

A translation is something like this:

“On 11th or 12th February 1942 criminal elements removed the tablet from the Copernicus Monument for political reasons. As a reprisal, I order the removal of the Kilinski monument. At the same time I give full warning that should similar acts be perpetrated I shall order the suspension of all food rations for the Polish population of Warsaw for the term of one week”

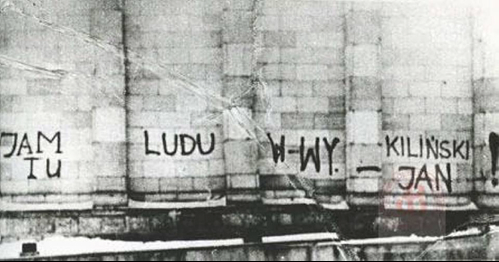

Now, Jan Kilinski was another popular historical figure in Warsaw, a shoemaker who led the fight against the Russians in a siege of Warsaw in 1794. His statue was indeed removed by the Nazis and stored in the vaults of the National Museum. By the following morning someone had painted in very large letters on the side of the Museum

“People of Warsaw, I am in here! Signed Jan Kilinski”

A week later, all of Fischer’s proclamations were over pasted with another announcement, printed in the same style. This proclamation read:

“Recently criminal elements removed the Kilinski monument for political reasons. As a reprisal, I order the prolongation of winter on the Eastern Front front for the term of two months.

Signed Nicholas Copernicus”

Now as it happened the winter of 1942 was indeed long and hard for the Germans on the Eastern Front. Fischer was tried for war crimes and hung in 1947. Dawidowski died very bravely in 1943 in an attempt to rescue fellow partisans from jail.