This is fun. Work it out for yourself.

I don’t know about Afghanistan, to me as a Brit it sounds like a Friday afternoon D4 in West Wales….

This is fun. Work it out for yourself.

I don’t know about Afghanistan, to me as a Brit it sounds like a Friday afternoon D4 in West Wales….

I’ve written a few times before about ship IEDs, which typically are massive devices sailed into an enemy port and then exploded after the crew flee. You can see my earlier posts on the subject by following the “Ship IED” link in the right hand column to this page. The earliest I have is 1584 and the “Hoop” used against the Spanish in Antwerp, and the latest is HMS Campbelltown used against the Germans in St Nazaire in WW2. In one of my earlier posts I mentioned in passing that such devices were used by the Royal Navy against Dunkirk in the 1690s. I have used a number of sources and there are some odd date discrepancies. The main attack on Dunkirk appears to have been on 1 August 1695 but I think there were other attacks at least one other using a “machine vessel”.

I have now found more details of these ship born IEDs used against Dieppe and Dunkirk in 1694 and 1695. The explosive component was designed and built by a Dutchman, Willem Meesters, who was contracted by the Ordnance Board in 1690 to provide the devices and convert a number of small ships. Meesters, favoured by the King, was appointed by the Board Of Ordnance to be “Storekeeper of the Ordnance” in the Tower of London in 1691. The attack on Dunkirk in 1695 was a complete failure and there was much recrimination between those involved and some of the blame was apportioned to Meesters. He was accused of “Cowardice and Misconduct” by the commanding admiral. The attack on Dunkirk, as did other attacks in that era on St Malo and other targets used a range of special ships. and it is important to understand the differences:

a. “Bomb Ships” are not ships designed to explode, they carry large mortars and bomb the target from close to shore

b. “Fire Ships” are disposable ships, which are set fire to and drift into enemy shipping, causing confusion, smoke obscuration and hopefully set fire to ships they collide with.

c. “Machine ships” are the ones we are interested in, with “infernal machines” which explode. They may be disguised as fire ships.

The technical detail of Meester’s “machine ships” is described in his proposal to the Ordnance Board. He proposed to use a watertight metal box fitted with a clockwork mechanism which acted on a flintlock as the initiator for other explosives. Around this box were packed barrels of gunpowder, scrap metal and “fireworks”. Some of his vessels were designed to explode with great violence and others simply to provide smoke screens.

Meester’s design, in general principle, is identical to both that of the “Hoop” in 1585, and the Campbeltown in 1942 – a mechanical time fuze set to initiate a massive improvised charge in a ship. I still find it fascinating that this near identical history of ship IEDs stretches so long over the centuries.

In May 1692, Meesters was authorised to purchase a number of vessels in which his ‘machines’ could be fitted. He bought, at first, seven vessels and some months were spent fitting them out for his purpose. All the ships were former Dutch merchant vessels. These were renamed, and by 1694 were based in Portsmouth, each with a crew of 10. A number of these were paid off and not used but the ones deployed operationally which exploded were:

1. Abram’s Offering, a 55ft vessel under Commander Edward Cole. This ship was recorded as “expended” during the Dunkirk attack in “September 1696”.

2. Saint Nicholas, a 70ft vessel under Commander Roert Dunbar. This was exploded in an attack on Dieppe in July 1694.

Then a series of smaller vessels were bought, each with a crew of 4. These were never used.

In 1695 four larger vessels were purchased and all were exploded in an attack on Dunkirk in August 1695. I have only the names of these vessels – Ephraim, Happy Return, Mayflower and the Wiliam and Elizabeth. All four of these “machine vessels” were set too early and didn’t get close enough to shore and caused no damage to the Dunkirk targets when they exploded. The admirals were not happy, Meesters was arrested, made to demonstrate another device, which itself failed. But he seemed to retain the patronage of the King, and remained in his official position at the Tower of London until 1701.

Despite the attack being a failure, I have found a treasury record that he was paid (three years later), the large sum of £3222 for provision of these machine ships for the attack on Dunkirk.

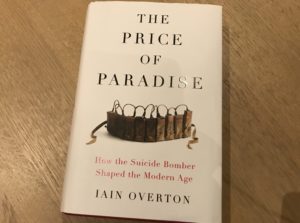

This blog, as a whole is driven by my personal interest and experience in dealing with the technology and tactics of IEDs. Almost deliberately, throughout my career, I have tried to separate away the technology and tactics from the politics and the motivations of those conducting the attack To an EOD professional, worrying about the politics or the psychology is a distraction at the scene. But that is not to say that they are not important. “The Price of Paradise”, by Iain Overton addresses the peculiar aspects of politics and motivation that produce suicide bombers and as such is a vitally important contribution to understanding the phenomena. It does not purport to be a book about “suicide bombs”, focusing on the human aspect of this mode of attack.

The book is a careful exploration, and thorough. It is easy to read, insightful and well worth its place on the shelf of the EOD professional, complementing perhaps references to technical and tactical aspects of the devices themselves.

I’m intrigued that Mr Overton traveled to many of the places where the attacks were carried out or instigated from, – St Petersburg, Lebanon and Sri Lanka and elsewhere, and the responses he had from the people there. I was affected by his habit of picking up a pebble here, a rock fragment there, and a flower in another place, removing nuggets from the places he visits, and in parallel picking nuggets of another sort from the people he interviews. It’s an effective methodology and gives the book a useful structure.

Mr Overton is also good at pointing out the laziness and the formulaic responses of western media to a suicide bombing, with journalists on autopilot seeking out negatives from the family history, to enable the easy story that fits the “loser” haunted by inner demons epithet. He also points that out sometimes professional psychologists have also failed to address the challenges of this complex subject. One take away is that we need a much better psychological toolkit. The book has made me think again about how “the spectacle” inspires others within the group carrying out the attack, and that aspect probably sometimes outweighs even the psychological fear of the bomber’s targets of the unknown face in the crowd carrying a hidden suicide bomb. So the “effect” of the bomb sometimes, in one sense, is more inwardly facing to the group of perpetrators than outwardly affecting their targets.

I learned quite a few new facts about suicide bombing – For example I was unaware of the link between the Tamil Tigers and the Hezbollah training camps in Lebanon in the early 1980s. I had also, until reading this, underestimated the level of cult-like importance that Tamil Tiger leader Prabakhakaran had on his followers. Similarly, I had perhaps underestimated too the cult-like leadership role of al-Baghdadi of Daesh. Elsewhere I was struck by the explanation of Pakistani “conspiracy culture” and tortuous but nonsensical explanations which causes a peculiar blindness to some acts of terror in that country and to a degree the Pakistani diaspora in the UK. Similarly he points out a matching, mirrored, moral blindness surrounding drone attacks by the UK and the US. I also found his exploration of the female and child suicide bombers insightful, especially their apparently different motivations.

I was moved in particular by Mr Overtons description, necessarily detailed, of the injuries caused by suicide IEDs. He clearly found this difficult to write about, but such reportage is necessary and too often avoided. This is a powerful chapter, it needs to be and he has done it well. I was moved again by the pieces on individual survivors, and their perspectives. Mr Overton tells their stories, tiny facets in a larger context with clarity and honesty, allowing us in our minds to extrapolate to all the others killed and injured in the same attacks.

In the later chapters of the book, the author examines some of the West’s responses, in terms of policing, intelligence and security, and the commercial opportunities these have driven, and points out much nonsense that exists in this area. I think he gets it mostly right, if at times he is a little unforgiving. The politics of counter-terrorism is a difficult conundrum. Terrorists kill way less people in most western countries than there are killed in road traffic accidents. Both sorts of death are nasty and gory but politicians often have the much smaller threat of terrorism at the top of their agenda, because it feels existential to their electorate. Generally it isn’t existential to the society it threatens. Terrorists might claim that it is but we shouldn’t believe them (I mean that last sentence on several levels of meaning).

Technically, suicide bombs are about as simple as you can get. They are essentially command-initiated devices with many of the unknowns or complications taken out. And that provides an attraction to the terrorist. No need to play with radio frequencies, encoders and decoders. No complex wiring. No need to risk exposure of the attack when laying a command wire. No need for complex teamwork. Explosives, battery, detonator, switch, maybe two. Nothing more needed. In a good proportion of suicide bombing attacks the bomber gets as close as possible to their target, not only to increase the chances of success but this also reduces the amount of explosives needed. There’s also a complex equation about the quantity of explosives a person can carry on them, against the distance they expect to be able to get from their target. So from my technical and tactical perspective, there are further reasons that the suicide bomb has become prevalent, that weave amongst the motivational and political described so well in the book.

But my technical and tactical interests also mean I notice any weakness where the author touches on such matters. Such things are pretty much irrelevant to most readers perhaps but since my audience here is mostly made of of people in the EOD game, I have to flag them, even if they appear picky. So… the book has the Russians defeated in the Crimea in 1851, which isn’t quite right – it was a few years later. The Crimean War has an interesting role in the development of explosive technology and I submit in the general public awareness of the potential of explosives. In particular, the device that killed the Tsar had a derivative of the “Jacobi fuse”, developed by Alfred Nobel’s father, Immanuel, for the Russian military at the time of the Crimea. A diagram of that Jacobi fuze, http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2012/12/24/the-russian-jacobi-fuze-1854.html consisting of a glass tube filled with sulphuric acid, which when broken is mixed with potassium chlorate is very similar to the suicide bomb initiation system designed by People’s will explosives expert Kilbalchich. http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2011/11/7/the-tsar-and-the-suicide-bomber.html In my mind, Kilbalchich’s bomb design is clearly derived from Nobel Senior’s munition design.

The book also defines dynamite as nitro-glycerine mixed with silicon, which technically is too much of a stretch for me. The role that the admittedly “silicaceous” kieselguhr plays in combination with nitroglycerine is much more complex than just “combining” with the material added to make dynamite. And Kieselguhr or indeed sand, is not “silicon”. But Mr Overton is spot-on in describing Alfred Nobels dynamite as an enabling technology for terrorist bombings, as was the fuze designed by his father.. Mr Overton is on slightly weak ground in other technical aspects, for instance describing a 5lb dynamite device as having a “blast range” of 1m. Firstly “blast range” isn’t a meaningful phrase, and the blast from 5lb of dynamite is certianly lethal well beyond 1 metre. Elsewhere there is a little confusion over certain, admittedly very complex, explosive effects and IED designs compared to conventional munitions. A few paragraphs on C-IED technology I found a little hurried and without clarity.

Other minor technical errors do not detract from the usefulness of the book, but to the technical minded, they are very mildly irritating. “Hexogen” is described as a semtex-like plastic explosive. Well, yes and no. Hexogen is RDX. RDX is a component of some plastic explosives, including Semtex, but it is the separate plasticiser which makes it plastic. Hexogen on its own is not a plastic explosive. Rather like saying raisins are like fruit cake. In the same paragraph, (which appears to be sourced from a NYT article) there is reference to “timing caps”, a strange phrase without a clear meaning.

In one sense this book is unfinished. The suicide bomb, enabled by the technological developments of the mid 19th century is here to stay, and with it huge complexities in terms of its users. This is not, unfortunately, the final word. We’ll see plenty more in the future, regrettably. But for now, this book is good, well written and useful. Recommended.

Here’s the story of two curious IED attacks that occurred during WW2. Different in nature, but with some odd parallels between the two.

The first attack took place in Tel Aviv, Palestine against the British Palestine Police in 1942. The target specifically was members of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) investigating the extremist “Lehi” group, aka “The Stern Gang”. This was a significantly complex IED plot, what might be termed a “double come-on attack”, using 3 IEDs, the latter two electrical command-initiated, targeting the responders to the first explosion. Senior members of the CID had had a number of successes against Lehi in the months prior to the attack. In particular Superintendent Geoffrey Morton and his subordinate Tom Wilkin were well known to the Stern gang. When Wilkin managed to arrest Lehi’s chief of staff for shooting a Jewish member of the Palestine Police, the Lehi leader, Avraham Stern, decided on very focused action against the head of CID (Morton) and his assistant Wilkin.

The plot was complex and multi-stage. A small explosion was made to occur in a roof-top room of a house in Yael St, Tel Aviv, as if it was a premature explosion in a Lehi bomb factory. The CIDs response to such an incident was well known and the Lehi assumed that Morton, as head of CID would attend the scene of the incident, along with Wilkin as he normally did to incidents involving Lehi. A second larger device had been hidden in the roof-top room, connected by a carefully concealed command wire to a waiting operative in a building nearby. Another command-wire initiated device was buried in a flowerbed just outside the house, providing another opportunity to attack responding policemen.

When the first reports of the explosion came in, Morton and Wilkin were involved in another matter so tasked other senior Palestine Police officers to the scene, saying they would follow shortly. Three officers went to the the house in question and went up to the roof top. Deputy Superintendent Shlomo Schiff was the leading officer, and was the senior Jewish officer in the Palestine Police. He had been the target of a Lehi assassination attempt the previous year. He was accompanied by Inspector Nathan Goldman and Inspector E Turton. As they approached the door of the roof-top room the command wire device was initiated. Allegedly the perpetrator mistook the uniformed police for Morton and Wilkin. Schiff was killed immediately and the other two succumbed to their injuries in following days. Morton and Wilkin arrived shortly afterwards but the third device was not initiated and was discovered later. It contained 28 sticks of gelignite. In police operations that followed a number of Lehi members were shot during raids. Stern himself was shot dead by Morton after being arrested. In a curious after-story, there was an attempt on Morton’s life three months later, another command wire IED on a car he and his family were traveling in. He escaped serious injury but later hidden IEDs were found at the cemetery where supposedly Lehi expected him to be buried, purportedly to attack mourners.

The second attack took place in Rome, Italy, in 1944, against the German SS “Bozen” Polizie Regiment. The attack target specifically was a mass column of German speaking Italian police, recruited by the Nazis from northern Italy, who regularly walked the same route on parade through Rome. Thus the column of marching troops provided a predictable target for the attack by the partisan “Patriotic Action Group” (GAP). The regular march by the column of police, paraded through Rome singing, around the Piazza del Spagna and into the narrow street of Via Rasella. The partisans prepared a large charge consisting of a steel container holding 12 kg of TNT, along with another bag containing more TNT and TNT filled metal tubing. The bomb was hidden in this hand cart.

A forty second burning fuze was lit as the marching troop approached (exactly the same technique as used in the VBIED attack against Napoleon in 1800). 28 of the SS policemen were killed in the explosion. The incident led to very significant reprisals by the Nazi authorities, including the dreadful Ardeatine massacre where 335 Italians were executed.

I think there are some interesting points shared by these attacks. Both were against police forces at least partially recruited or sponsored by other nations. Both exploited the predictability of their targets, albeit in different ways. In both events the aftermath of the IED attacks led to further nasty tragedies. In war the focus of history is on the front line battles between armies. But Home fronts also provide an environment for IEDs and the police are often the targets but are often forgotten in some history books. Patterns of IED tactics seen today appear as we look further and further back in time.

More on interesting railway attacks. During the years after WW1 up to Israeli Independence, the British forces in Palestine came under repeated attack from both Arab and Jewish Groups. I posted a picture of one (immoral) counter-measures used in 1936 against Arab attacks here. I’ve also found some details of Jewish militant devices from both Irgun and Lehi (the latter referred to by the British Army as the Stern gang).

Probably the most significant of the Lehi attacks was in late February 1948, a few days after the VBIED attack carried out by British Army deserters in Jerusalem, described in an earlier blog here. In this railway attack electrically initiated command wire IEDs were used to attack the train carrying British troops from Port Said near Cairo to Hiafa. The attack occurred just outside Rehovot. 28 British soldiers died in the attack. The command initiation point was in a nearby orange grove, with a full view of the train as it ran along an embankment.

Interestingly the intensity of the bombing campaign was so high in 1946 that the British military, reducing in size following WW2, were short of EOD operators, and so sought volunteers. This is an interesting quote from one of those volunteers

“District asked for two volunteers to attend a Bomb Disposal Course in Jerusalem. I don’t know how many fools applied but I was one of the Twelve Apostles that found themselves rather hurriedly in Jerusalem. For our tutor we had a highly experienced Sapper Major; His opening words to the twelve of us as we sat in the classroom in the Police Depot at Mount Scopus were as follows: ‘Gentlemen. I have seen Bomb Disposal service in France, the African campaign, Sicily, Italy, France and Germany, and now here. I am wise and experienced, but here I haven’t a bloody clue.’ It was like a sentence of death.” My Trinity, Eric Howard.