I’m afraid this is going to be a long and detailed post, but it is one of the most interesting historical explosive devices I have ever written about. Despite the length, I must urge a little caution. I’m working from a very small number of poorly translated documents, about a technology that is at the edge of my understanding, and about which there are conflicting assessments and denials. I have some Russian references but my Russian is very poor and worse now through lack of use. Very happy for input from anyone who has a better handle on this or who sees errors in my analysis.

In the 1920’s and 1930’s the Russians developed a number of radio-controlled systems. As an aside, this included radio-controlled tanks. Another system, and the subject of this blog piece, was the F-10 radio-controlled mine. This mine was first developed in 1929 (90 years ago!) and deployed operationally in 1941 in the “Great Patriotic War” (WW2) against the Germans, most notably in Kiev, Kharkov and Odessa, and against the Finns in what is called the “Continuation War”. Their use came to a real crescendo in September/October 1941. There are several very interesting aspects to the device, – its design, its employment/and the MO of its use, the highly ambitious planning and significant operations it enabled, and the reprisals that resulted. Furthermore, the electronic countermeasures employed by both the Finns and the Germans at great speed following technical exploitation of captured systems provide useful historical vignettes about rapid fielding of EW against radio controlled explosive devices.

By necessity, I have to get a little technical, and to repeat, some of my technical assessments and understanding might be wrong, but I’d like to get this out there rather than spend a year refining peculiar technological aspects.

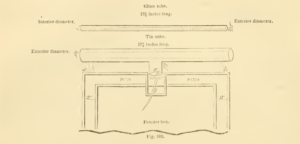

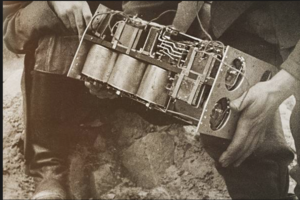

So firstly, the design of the system. Here’s an image of the main receiver (Rx) of the system. I think this image is actually German, following a render-safe procedure:

The receiver is a briefcase sized radio and decoder, and I’ll come on to the detail of that shortly.

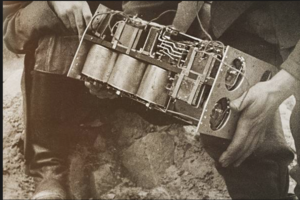

Below there is a battery, a radio box, and the rubber bag in which the device is placed when concealed (usually buried) and what appears to be detonation cord or cables, perhaps leading to a large explosive charge.

Here’s an image of the batteries and radio enclosed in the rubber protective bag , ready for burial and concealment.

The system is designed to recieve a coded signal , and detonate up to three explosive circuits. The complete device, less explosives, weighs 35kg. There is a 30m antenna, which according to the references can receive a signal if the antenna, placed horizontally, is buried in the ground up to 120cm (some assessments say less), in water of a depth up to 50cm or hidden by brickwork up to 6cm – Grateful for comments on this aspect from any EW experts or RF engineers.

The system has a complex timing system. Using the batteries alone would give an operational life cycle to the radio receiver and enable power to the explosive circuit of 4 days. But a mechanical timing system is integrated to give a complex range of operations, including a long time delay before activation or providing a number of time “windows”, from as short as 2.5 minutes “on” to 2.5 minutes “off”, and other longer on-off windows, giving a maximum receiver power life of 40 days. There is a complex relationship between the length of time windows and the length of the command signal required that I don’t fully understand. Suffice to say, that several frequency signals in a sequential row need to be transmitted for the decoder to accept a command, and the length of those individual sequential signals isn’t quite clear to me, but is at least a minute and sometimes longer.

Additionally, there are some clever extras… It is possible to set a mechanical time delay to explosive initiation (avoiding the Rx) of up to 120 days. If I understand it correctly, this was usually set as a last-resort back-up self-destruct. It is a mechanical clock and some EOD successes were made by detecting the ticking clock. The explosive contents used with F-10 varied from a few tens of Kg to several thousand Kg.

The device also was fitted or could be fitted (I’m not sure) with anti-handling switches. The anti handling switches quoted in the spec are “EHV, CJ-10,CJ-35, CMW-16 and CMW-60” I haven’t investigated these yet but at least one is a pull switch attached to the opening of the rubber bag the system is deployed in.

The range of the command system of course depends on the power of the transmitter. From German exploitation of a captured F-10 device, the frequencies employed reportedly range from “1094.1 khZ to 130khz”. Again I welcome comment from EW specialists. This implication is that the “setting” of each F-10 mine to specific frequencies was quite flexible and easy but I’m not sure quite how it was done. Perhaps by replacing individual tuning forks? I have found one reference, a Finnish technical exploitation report, saying the tuning forks were colour coded, which would be logical. Another report suggests that the radio receivers were marked with a numerical code in roman numerals, which defined the initiation frequencies. A slightly contradictory early Finnish exploitation report, very interestingly, suggests that two of the frequencies allocated to the F-10 were set to pre-war popular music radio stations from Kharkhov and Minsk, with a specific “calling tune”. I can’t quite make sense of that, but never mind.

The decoding system predates DTMF of course. A system such as the F-10 needs to be able to discriminate random signals from an actual command signal, so this system uses (I think) a triple tuning fork mechanism, with specific successive frequencies transmitted over a time window. Only when three successive signals of different specific frequencies, each of a sufficient duration, are received will the “AND” logic of the system allow initiation.

Such a capable system allows for a wide range of operational designs, or employment plans. It is clear that the Russians used these in areas where they ceded territory, so they are “stay-behind” sabotage devices. They are expensive too, compared to other mines and challenging and resource-heavy to deploy effectively. So to justify that, the targets have to be significant. Initiation could be by a separate line-of-sight concealed engineer team using a transmitter quite close, or indeed could be several hundred km away (I think). So the device could be under observation and initiated at the optimum time, or more remotely, without line of sight, perhaps based on intelligence.

In the Finnish campaign, the Finnish military encountered quite a few of these devices as they re-took the city of Viipuri in September 1941 and rendered at least one safe. One such item is on display in a Finnish military museum. As a result, it is alleged, they developed an electronic counter-measure, which was to set up a permanent high power frequency transmission on one of the first two frequencies. This overwhelms the timer element of the decoder and perhaps jams incoming other frequencies from the system with its power. That, sort of, makes logical sense to me but I’d appreciate comment from any ECM experts. I have seperate reports, hard to confirm, that the “jamming signal” was a piece of music transmitted at high power over and over again at a fequency of 715KHz. In response the Soviets changed the frequency of the F-10 systems. and the Finns responded by putting the same song out, constantly, on every frequency they could, apparently

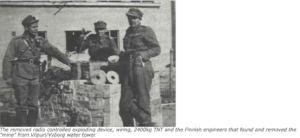

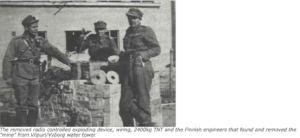

Here’s an image of a Finnish EOD team and the F-10 recovered safely from a water tower in Vyborg. I’m pretty sure the “wall” they are leaning against is TNT blocks.

The removed radio controlled exploding device, wiring, 2400kg TNT and the Finnish engineers that found and removed the “mine” from Viopuri/Vyborg water tower

On a more practical level, Finnish engineers worked out that the long 30m antenna gave them an opportunity to locate the mine. In any places where they suspected a buried F-10, they dug a small trench 2 ft deep, around it, and if there was a mine hidden there, they invariably encountered the antenna.

As an aside, I understand that the young Finnish Officer (Lauri Sutela) who rendered safe one of these devices in September 1941 in Vyborg rose to be Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces in the 1980s. There’s always hope then for young EOD officers to make their way in the world…

German EW responses to radio control initiation appear also to have been developed and deployed quickly. They captured an F-10 mine in mid September 1941 and it appears there were countermeasures deployed, apparently by 25 October at the latest. That’s pretty fast for a capture, technical exploitation to deployed countermeasure cycle.

German countermeasures included:

- Digging an exploratory trench looking for the antenna as the Finnish engineers did. Quite often Russian prisoners of war were used for this task.

- Use of an electrical listening microphone to listen for the mechanical clock component

- A responsive jamming capability to transmit, quickly, a powerful “blocking” signal if any known F-10 frequencies were detected. I don’t think this was automated.

- There was another RF method developed, apparently of limited use, which involved transmitting a “disabling” signal, somewhere “between 150 – 700Hz” but I cant quite make out the sense of that. Again advice accepted, gladly.

When the Germans took territory from the Russians, in 1941, eventually the cities of Kharkov, Kiev and Odessa were ceded.

In the run up to Russian withdrawal from these cities, engineer teams in significant number laid a wide range of mines and booby-traps for the advancing Germans. The Russians worked out that quite often Germans would take over large buildings that had been used for Russian military headquarters, and use them for their own headquarters. It appears that although equipped with a wide range and number of relatively cheap mines and booby traps, the expensive radio controlled mines were used in a very focused manner to target senior officers and their staff in headquarter buildings. The Germans moved into large office buildings (as previously used by the withdrawing Russians), presumably because they had the scale, number of rooms and perhaps even telephone lines. So a vacated Russian Army HQ would become a HQ for the advancing Germans. This provided a predictability that the Russian engineers could exploit. Russian engineers became expert at laying “slightly obvious” booby traps which German EOD would render safe and then assume the ground underneath was clear – but actually often there was an F-10 radio controlled mine buried deep and everything including the antenna was much more carefully concealed.

In the captured cities of Kharkov, Kiev, and Odessa, German generals and their Headquarter staff were killed by concealed F-10 devices over a 7 week period in 1941, as follows:

Between 24 and 28 September, numerous F-10 devices were exploded in central Kiev in buildings occupied the prior week by German Army headquarters. The F-10 devices were allegedly initiated by command from stay-behind hidden engineer units observing the area from an island on the Dneiper river. In particular an explosion on 24 September hit the Rear Headquarters of the Wehrmacht army Group south killing a large number of officers, including the artillery commander of the 29th Wehrmacht Corps. In immediate reprisals the massacre of Babi Yar took place, with a death toll of 100,000.

On 22 October, the Romanian Military Headquarters in Odessa, established 3 days earlier and manned jointly by Nazi and Romanian military staff was exploded up by an F-10 device (I believe) killing 67 people including the Romanian General. 40,000 Jews were killed in reprisals.

On 14 November, multiple buildings just occupied by German forces in Kharkov were destroyed I think with F-10 devices. There were hundreds of casualties, including the German commander, Generalleutnant Georg Braun. In immediate reprisals 200 civilians, mostly Jews, were hung from balconies of surrounding buildings. The following month there were further reprisals and 20,000 Jews were gathered at the Kharkov Tractor Factory. All were shot or gassed in a gas van over the next two months.

It is hard to get to the bottom of how many F-10s were used in these cities but I think they were used in significant numbers, alongside extensive conventional mining and booby trap techniques. I think historians in regarding these cities separately in the Eastern front campaign miss the point that this was a clear strategic effort to deploy these weapons to “cut off the head” of the advancing German armies. The fact that these attacks came at the same time as their use in the Vyborg peninsula against the Finns, cannot be a coincidence and I sense a strategic decision to employ these weapons as the Soviets were being pushed on all fronts. In the main, use of the F-10 was part of operations under the command of a remarkable explosives engineer, Col Ilya Starinov. I will be returning to discuss Starinov in future blog posts, suffice, for now, to say he was ultimately responsible for more explosive attacks on trains and railways than any other man that has ever lived (by a long way) and fought in at least 4 wars as a Russian explosives expert. He really was the instigator of Soviet Spetznatz tactics.

This F-10 radio controlled device then poses a fascinating case study of an early radio controlled explosive device threat, and how a technical capability (in this case of a pretty flexible system) when coupled with intelligence and innovative employment can pose significant threats not only to whatever troops are in its path, but also targeted specifically on high value enemy leadership as part of a strategic plan. The appalling reprisals to these F-10 attacks suggests the concern felt by the Wehrmacht.

This story also demonstrates the rapidity that is possible with suitable technical intelligence resources and processes to develop both technical and procedural countermeasures. The RC threat and response game is nothing new.

Update:

I’ve been looking further into how the F-10 radio controlled mine was designed. In itself it is an interesting story. In 1923, the Soviets started up a “Special Technical Bureau” for “Military Inventions of a Special Purpose” known as “Ostekhbyuro” in typical Russian fashion. The two people credited with the invention were V. Bekauri and V Mitkevich. Bekauri, was instrumental in developing a number of other Soviet radio controlled systems including the Teletank and other guided weapons. I believe the work on the F-10 mine was completed in 1929. In 1932 the devices were taken on by a specially constituted military Unit, I think designed to exploit the specific capabilities of these devices. The radio controlled mines were at first referred to as “BEMI” mines, named after the first two letters of the last name of each inventor. Later they were re-designated F-10.

In 1937, Bekauri had risen to be Director of the Ostekhbyuro, but was arrested, interrogated, charged with counter-revolutionary behaviour, found guilty 15 minutes later and then executed as part of Stalin’s purges in 1937.