This is quite startling. I have written before about Boer use of upturned-trigger-initiated IEDs used to attack British Railways in the Boer War, and more recently about how the same design of IED was used in the German East African Campaign

These devices were used again, exactly this same design, by the British against the Ottoman rail system in Arabia in 1917. One of the issues in my mind was how “Bimbashi Garland”, the Arab Bureau’s explosives expert, got to hear about Boer IEDs from an earlier war. In British eyes, this Boer design, then adopted by the Germans in 1915, became, by 1917, the “Garland mine” . Thanks to the research of “JB” we have an answer as to how that happened and what an interesting answer it is. Bear with me as I explain

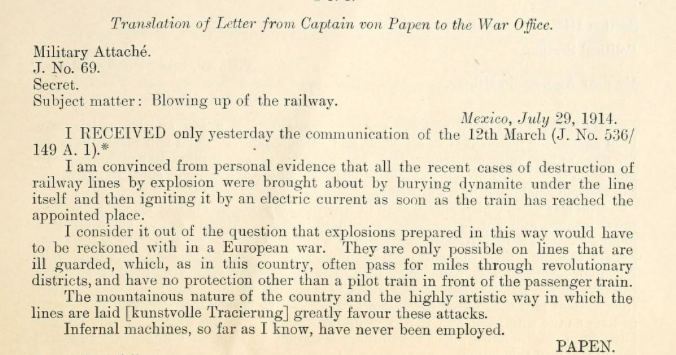

Here are parts of a letter sent from a relatively senior British Army officer with previous campaign experience in the Boer War. He sent a letter to the British Army in Egypt suggesting, specifically, that the Boer explosive device he had seen many years previously in South Africa be used to attack the Hejaz Railway in Arabia. Not only that, but he includes a detailed description of the device, which with minor variations is clearly the same device.

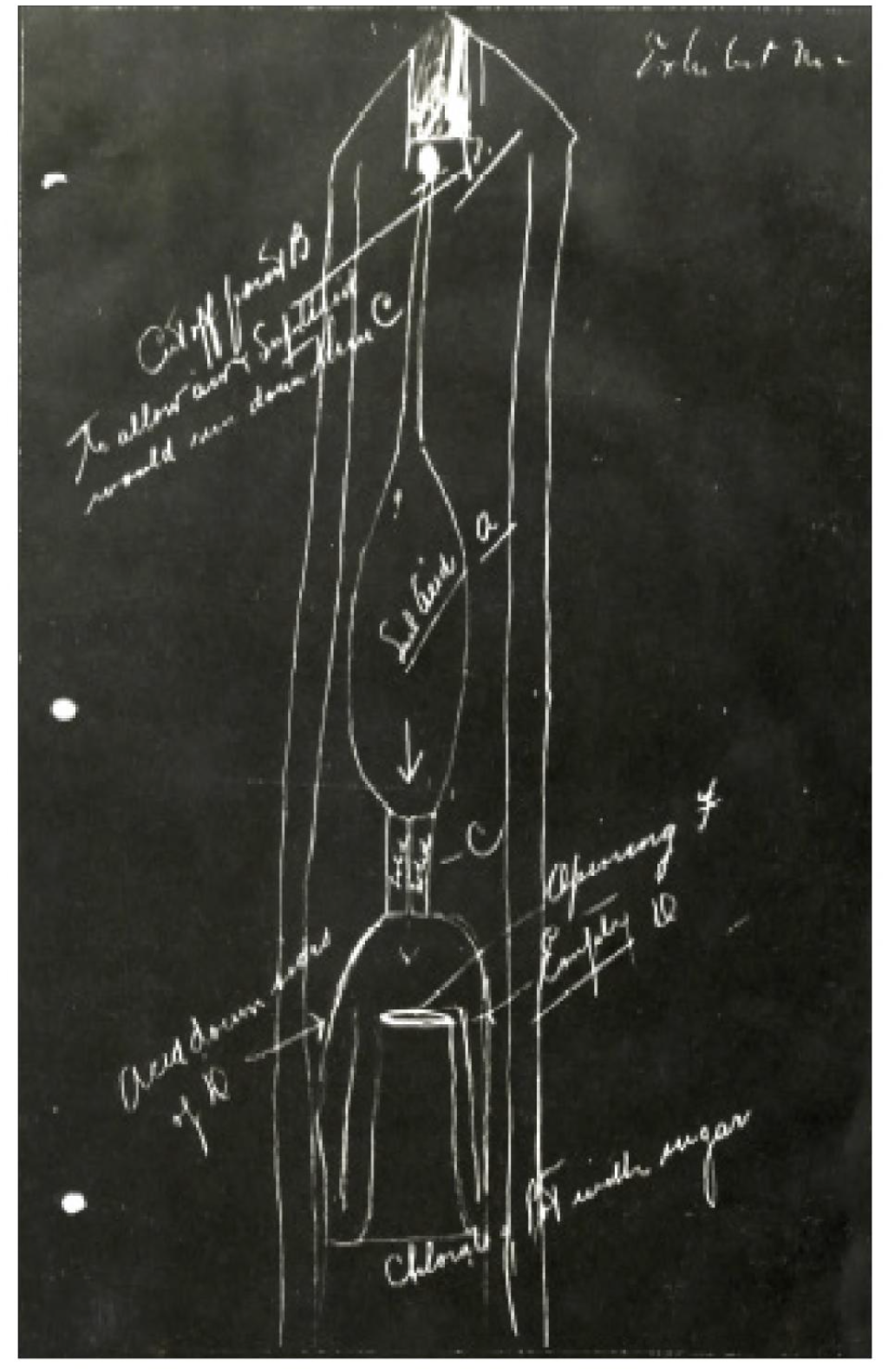

For comparison here’s a diagram of the device from one of my earlier posts

The correspondence is then passed from British HQ in Cairo to General Reginald Wingate whose headquarters was in Khartoum, with some comments from the Fortifications and Works Department. Of particular note here is that they refer to the German use of such devices in East Africa, and comment that these devices have been effective. Here’s the comment from a Sgt in the Fortifications and Works department.

So that’s interesting… but it gets better. The original letter was dated October 1916. Herbert Garland, the former Ammunition Examiner NCO, now with a commission and on the staff of the Arab Bureau, shortly afterwards began working “behind enemy lines” with the Arabs, and taking the advice/instruction of the letter writer , made his first attack on an Ottoman train in February 1917 – so the dates match up. Subsequently he trained the Arabs and other British officers on similar missions, including Lawrence of Arabia, to do the same. So we have a nice link between the Boer War, the German East African Campaign in WW1 and now the Arab revolt of 1917, all using the same design of IEDs, now called the “Garland Mine”.

What is perhaps even more interesting for historians is the identity of the original letter-writer, that at first I confess I didn’t notice. It is written by Colonel Sir Mark Sykes… Sykes is perhaps the key personality in terms of strategic influence on British activity in the Middle East, way beyond Lawrence. Sykes, with the French diplomat Picot, was responsible for the “Sykes -Picot” agreement which divided the Middle East, and specifically the Ottoman Empire, between the British and French, and this strategic diplomatic activity was going on at the same time as the letter was written – so this is so much more than a retired Army officer pontificating about how what he learned fighting against the Boers could have application in “modern war”. This is the lead British strategic diplomat in the Middle East politely and diplomatically directing that an IED campaign using this specific explosive device be used to disintegrate the key aspect of the Ottoman empire’s strategic hold on Arabia. In the usual history books the strategic direction of the Arab Revolt is sometimes credited to the “Arab Bureau” but there were bigger cogs turning and directions being given to them. The Bureau’s efforts were at the operational level in this regard. Here we can see history was being made in the Middle East and with these specific IEDs and with strategic thought. And not for the last time.

(Apologies for the racism displayed in the Sykes letter, but it is important to see, and perhaps adds to our understanding of his thought processes and how they may have impacted his strategic efforts)

Roger Davies

Roger Davies