There’s a lot of attention given these days to the dissemination of such things as “Inspire” the extremist jihadi online magazine about how to build bombs and such like.

The truth is that this, like terrorism itself, is nothing really very new. In 1884 the anarchist Johann Most published “Revolutionare Kreigswissenshaft”, a self proclaimed scientific handbook for would-be revolutionaries. Johan Most popularized the concept of “Propaganda of the deed.”

While the modern day jihadist spreads his technology concepts by such things as “youtube”, “web forums” and “on-line magazines”, Johann Most used “printing presses” and “bookshops” and “newspapers” to the same effect.

Most and his work are an interesting tale. Most was born in Germany in 1846, and lived in England for a few years from 1878. Some of those English years were spent “at Her Majesty’s pleasure” in prison. He was an ardent and open revolutionary. Finally he moved to the USA 1884, and was employed by an explosives manufacturer in New Jersey, building some small degree of technical expertise. He published his book in 1884 and it is still available today still. I ordered mine openly from Amazon and I think I can justify it to the authorities.

The context of the situation in 1884 is important to understand. My American friends will, I hope, forgive me when I say that it was a pretty easy place to build IEDs. A number of US citizens were openly involved in building IEDs for profit and training people to use them.

Here’s one example of a bomb maker from Philadelphia of the same period. And another here from an earlier blog post on this site. . I have records of several others including a man in Des Moines in the 1880s who was manufacturing IEDs to be sent to support the Fenian bombing campaign in London. Iowa was a hotbed of anti-British “Fenian” feeling! Then in 1886 was the Haymarket bombing in Chicago, which I have written about in an earlier post.

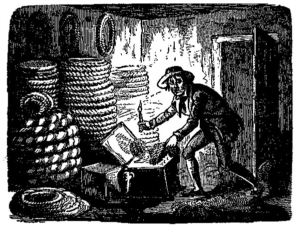

The Haymarket bombs were of a type described by Most in his handbook published two years earlier. There is a link, allegedly with Most promising to send the Haymarket conspirators dynamite. He really pushed the “classic” anarchist IED of a black sphere with a burning fuse projecting from it.

The truth is that Most’s understanding of explosives is nowhere near as good as he thought it was. Perhaps that too is like modern extremist publications available on-line. The handbook has numerous technical errors but is all the more interesting for that. Clearly I’m not going into those errors here, but it’s pretty interesting to see his revolutionary ardour overtake technicalities. I would also add that most copies available are translations and I think there are some peculiar spelling errors and possible technical misunderstandings of the translator. For instance in the copies I have seen, Most describes “Oraini bombs”, which should I think read “Orsini bombs”. Also the translator clearly has no technical background – at one point complaining irritatedly that Most’s phrase “Cloral de pottage” doesn’t appear in any of the University of Arizona’s French Dictionaries. It clearly means Potassium Chlorate to anyone with a smidgen of understanding of the chemistry of explosives.

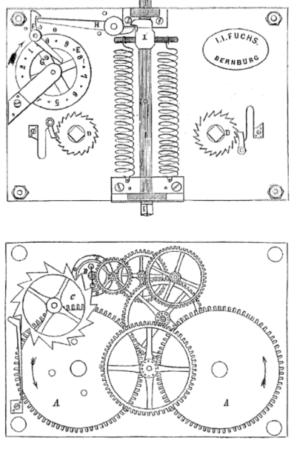

Most describes the manufacture of the chemical impact fuzing system that was in the IED used to assassinate the Tsar in 1881.

Interestingly Most advises that it is easier to obtain nitro-glycerine or dynamite legally or illegally than it is to manufacture it. Amusingly, as a revolutionary, Most doesn’t describe it as “theft” but “confiscation”. But then describing the manufacture of nitro-glycerine he views with disdain some of the safety measures that are normally advised for such projects. Most’s instructions are not detailed or specific enough and are subject to dangerous misinterpretation, especially , I suspect, the translated versions, translated by a non-chemist who I don’t think has much technical understanding.

Most describes a way in which explosives should be used to cause damage to buildings and railway lines, but most of this seems to be a “cut and paste” job from Austrian military handbooks of the time. Again, somewhat like certain extremist sites of today who recycle conventional military handbooks.

Most does occasionally have some very pertinent ideas about such things as disguise of devices.

Most describes the manufacture of a range of explosive charges and also primary explosives and incendiary devices. There is an odd, and somewhat silly section about poisons, but no sillier, I suppose than some of the nonsense on extremist websites today. I can’t really imagine copper acetate is a serious poison for the serious terrorist. He also has ideas about operational matters such as organization of an operational terrorist group.

Most takes an interesting view on the question of the right to bear arms, which he equates directly with the right to possess explosives. He attacks US lawmakers of the era who were trying to make the possession of explosives illegal, which he viewed as a first step along the road of making weapon ownership illegal. “How then would the American revolutionary be able to shoot the lawmaker?”, he asks indignantly. Finally, Most describes some very “modern” OPSEC procedures.

So the history of disseminating terrorist technology and tactics goes back an awful long way. Most was doing exactly what “Inspire” is doing now, just with a different level of media. You’d be surprised at the similarities.