I have written before about the IED attack on Napoleon Bonaparte on Christmas Eve 1800, and I am slowly uncovering more and more details. These include:

- Detailed costs of medical support and pensions for the families of victims.

- Details of the 25 houses damaged by the explosion, and examples of that damage.

In the investigation that followed, a gentleman called Chevalier was arrested, and an “infernal machine” in his possession was seized. This was a command initiated device, and “Citizen Monge” a member of the office of the Prefect of Paris was assigned to examine it.

The device was described as follows:

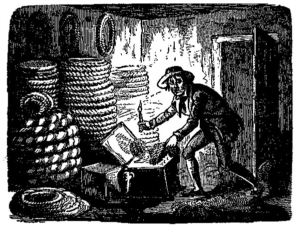

This infernal machine consisted of a barrel hooped with iron, and filled with balls, maroons and gunpowder. To this machine was attached a gun barrel, heavily loaded. This machine was placed on a wagon, laid on purpose to intercept the way and discharged by the aid of a pack thread from a neighbouring house. The intent: was, that its discharge should overturn and destroy everything that was near it.

A separate report has Chevalier admitting that it contains six or seven pounds of powder, then:

In this barrel is securely fixed a musquet loaded, but with the stock cut off. This machine is placed on a small carriage, which unexpectedly, and at a given signal is pushed into the street to obstruct the passage, and then by means of a string the trigger of the musquet is pulled and the whole machine blows up.

The use of a trigger mechanism from a firearm is of course well known and I have blogged before, several times :

- Fulton, the American explosive device designer (who intriguingly was kicking around Paris at this time and in 1801 developed an underwater mine initiated by the very mechanism described above )

- The Boers and Lawrence of Arabia, here

So who was this Citizen Monge to whom the task of examining the device was given? It turns out Gaspard Monge was a technical and scientific adviser to Napoleon and a famous scientist. He was held in very high regard by Napoleon. Monge was interested in explosives, and ordnance and wrote books and papers on the subject. Monge was tasked earlier in 1800 by Napoleon to consider Fulton’s inventions.

Once again I’m struck by several issues:

a. Technical examination of IEDs goes back over two hundred years.

b. Simple adaptation of firearms to initiate IEDs can be found repeatedly over history.

In doing this research I’ve uncovered much more about Fulton and his devices – which I’ll return to in future posts