A friend of mine asked me my opinion on the most significant terrorist attacks in history. Here’s one which had pretty significant implications.

“John the Painter ” aka James or John Aitken, aka Jack the Painter, aka John Hill aka James Hinde was born a Scotsman but adopted America as his cause. A petty, and not so petty, criminal he made his living as a painter and clearly his daily dealing with turpentine and flammable liquids prompted a thought. He was also seized with enthusiasm for the cause of Independence for America, having arrived there in 1775. He became a prototype lone wolf terrorist.

In 1776 he knocked on the door of the leading American diplomat in Paris, France, Mr Silas Deane, and with a little encouragement described a plot to set on fire the key naval dockyards in England, thus crippling the British Royal Navy. He showed Deane his incendiary device:

Producing a portable infernal machine of his own invention, he explained his scheme. The machine consisted of a wooden box to hold combustibles, with a hole in the top for a candle, a tin canister, no larger than a half-pound tea can and perforated for air, to cover it; the whole to be filled with inflammable materials—hemp, tar, oil and matches. The candle, having been lighted, would burn down until it ignited the inflammable materials, and these exploding would scatter the fire for yards around.

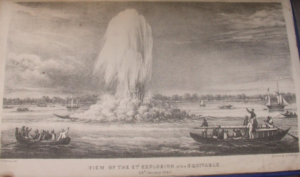

Deane gave him a little encouragement and a little money and sent him on his way. On returning to England, John the Painter successfully burnt down the Rope House at Portsmouth Naval dockyard. He also set a number of fires in Bristol. This created the public impression that gangs of American revolutionaries were active in the country. The King himself offered a reward for his capture and demanded daily briefings.

In an early form of Weapons Intelligence Investigation a failed device of the same design was discovered in an adjacent building to the burnt down rope house and subsequently witnesses attested that John the Painter had had it made in Canterbury. John the Painter was hunted, arrested and tried – the transcript of his trial is available on line in Cobbett’s State Trials. The device is described very clearly on a number of occasions by witnesses. An intriguingly thorough trial even down to the calling of a witness from whom he had bought matches.

He was duly transported to Portsmouth where he was strangled at the gates to the Naval Dockyard then hoisted up the 64 foot mizzenmast of the HMS Arethusa [specially unbolted and placed on land for the occasion] then they eviscerated his body, tarred it, hauled it back up the mast and left him to waft in the wind for years as a warning to all and sundry.

The mast was the highest gallows in England’s history. 20,000 people attended the execution (quite a number, given the population of Portsmouth was 13,000)

So, why was this so significant in its implications? Here’s why:

- The fires in Portsmouth and Bristol caused terror across England. Vigilante groups patrolled the streets of ports. Thus the arson attacks really did terrorize the nation.

- The attacks turned the public opinion – there had been significant support for the American revolution, especially in Bristol, but this public support was turned on its head. Had this not occurred, and more negotiated independence may have been achieved. Who knows what that may have looked like?

- The public mood allowed the production of the 1777 Treason Act and for years after the death sentence for murder in the UK had been abolished in 1965, the death sentence was still permitted for treason, and explicitly included in the list of treasonous acts was arson in the naval dockyards.

A newspaper of the time stated:

“Of all bad characters, an incendiary is the foulest. He acts as an assassin armed with the most dreadful of mischiefs, and in executing his diabolical purposes, involves the innocent and the guilty in the same ruin.”