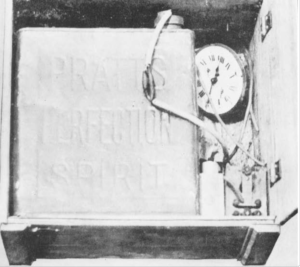

I’m currently digging in to instances of the British Army using IEDs in various campaigns. There’s a couple of interesting stories from the Siege of Mafeking (1899-1900). The British were surrounded at Mafeking and held out for quite a period against the Boers. They were short of supplies, but led by Baden-Powell used all sorts of ingenious methods, including improvised explosive devices (and hoax explosive devices) to keep the Boers at bay. Certainly the Boers were intimidated by the threat of these improvised landmines (often placed in likely artillery positions). The Boers too made extensive use of IEDs at this time.

Other munitions were developed at a workshop in the railway yard. There were a large number of improvised grenades made , using dynamite, a tin can and a burning fuze. Other IEDs used Boer artillery shells that had failed to function, and indeed on more than one occasion using recovered Boer IEDs that and been rendered safe. Here’s the description of one such, by Baden-Powell the Garrison-Commander, talking about a forward Boer position that they abandoned:

Their somewhat noisy retirement made me suspicious, and two scouts were sent on to see if all was clear. They found some wires, quite newly laid, and a mine of nitro-glycerine, so something equally soothing, awaiting our entrance into the work. The wires were therefore cut and wound in for future use against the layers. And while we sang ‘God save the Queen,’ the Boers were probably touching the button at the other end of the wire with considerable impatience at their failure of their fireworks.

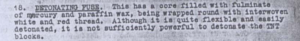

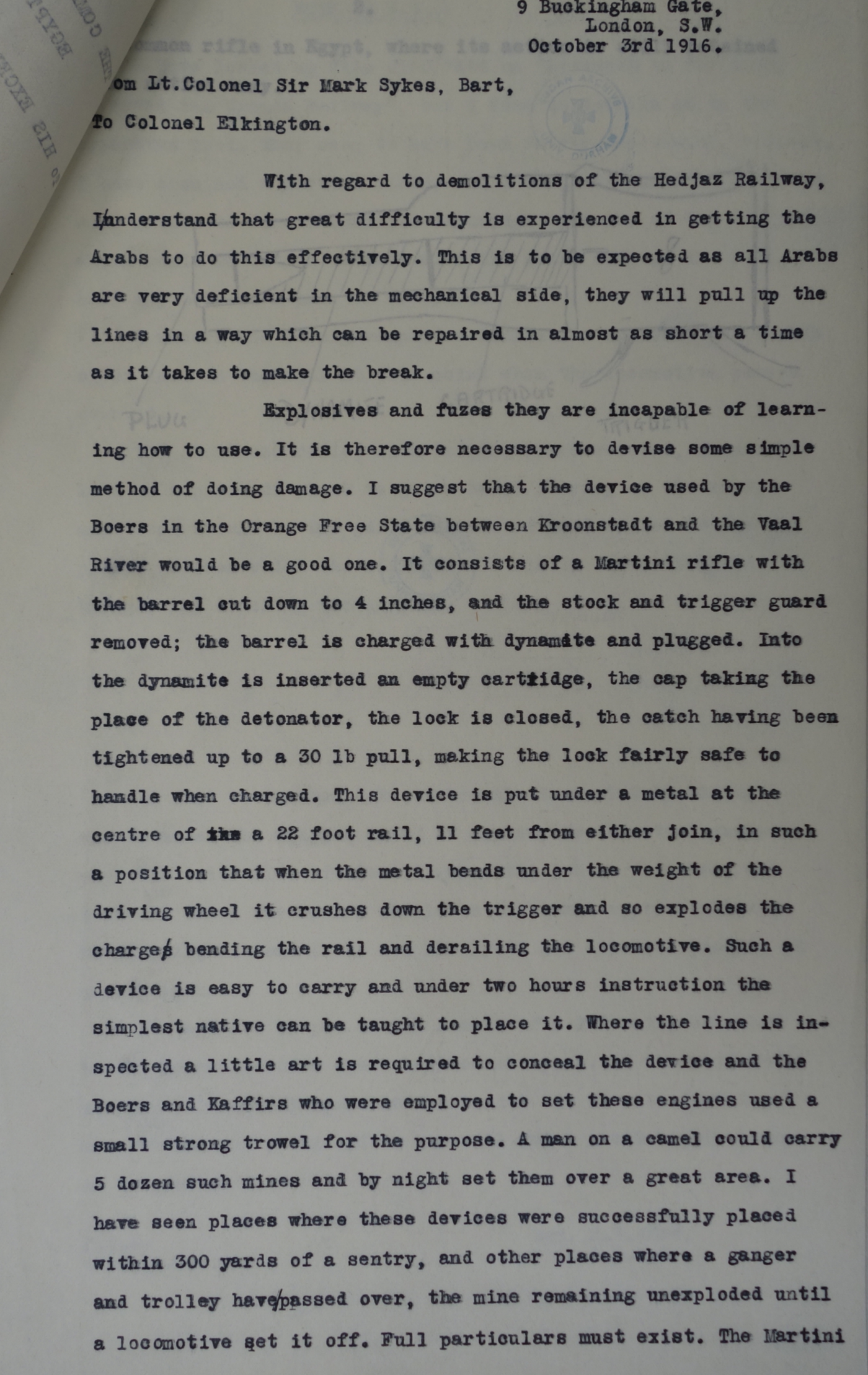

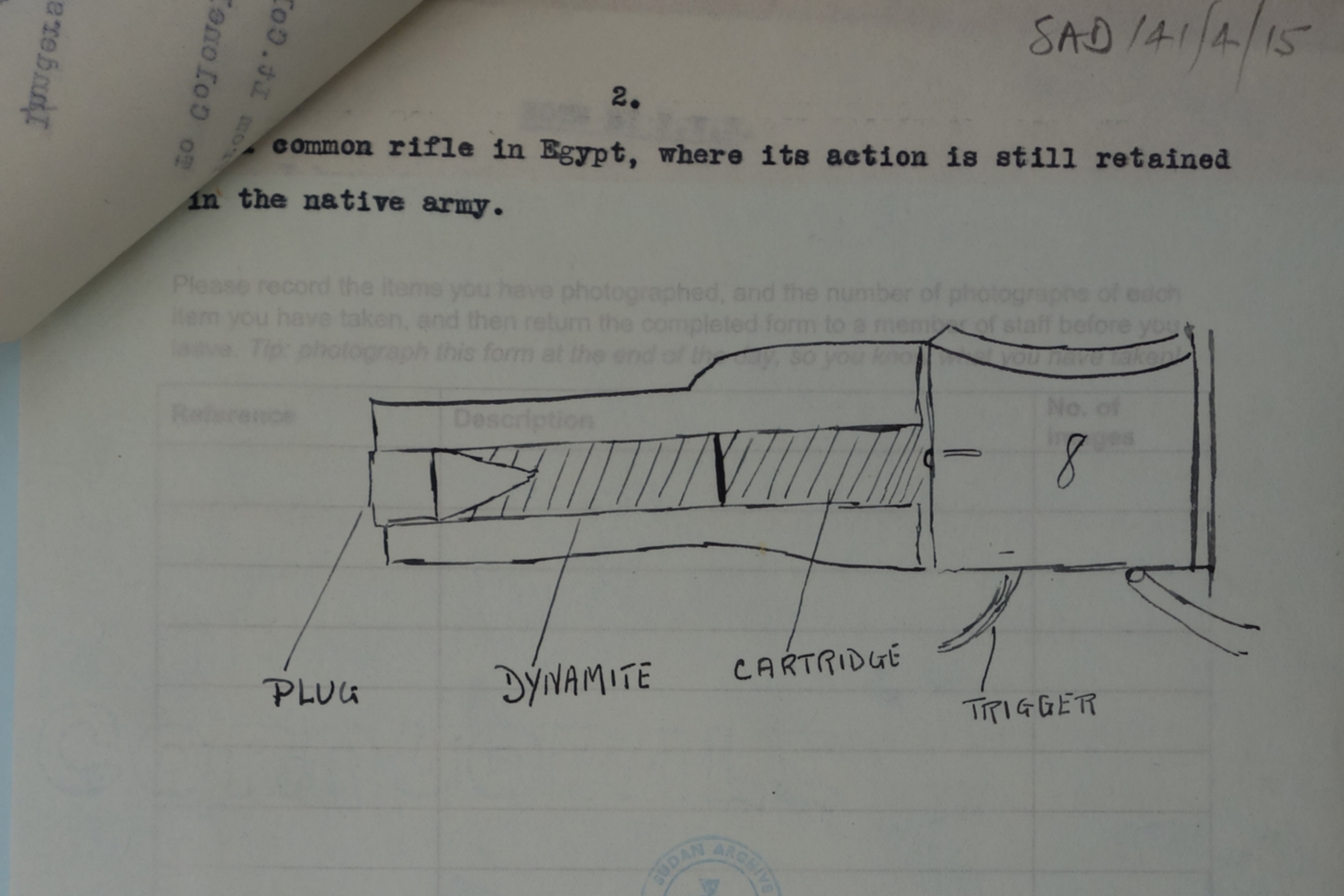

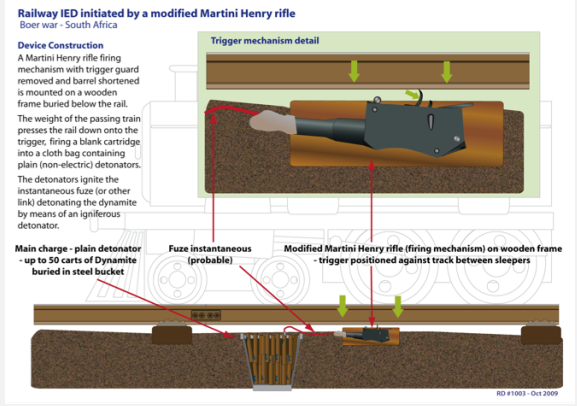

Seasoned “standingwellback” readers will recall that I have written before about Boer railway line IEDs here.

The defenders too used electrically initiated IEDs – one here was awarded a “Mention in Dispatches” thus:

Koffyfontein Defence Force-Corporal H J Jellard (promoted Sergeant); on October 11, for exposing himself to heavy fire at 60 yards’ range when getting on to a debris heap to connect a wire from a battery to a mine, and also for holding an advanced position with assistance of one native

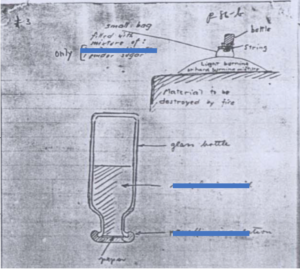

One particularly effective method of delivering improvised grenades to the target was drawn by Baden-Powell himself – no mean artist:

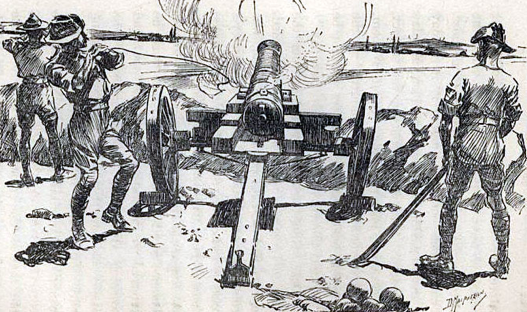

Sgt Page (other reports name him as Sgt Moffatt) used a fishing rod and line with the grenade attached to the end of the casting line. Apparently he could deliver the improvised grenade a distance of 100 yards with some precision. Baden-Powell suggest that the fishing rod technique replaced a mechanical spring device which was less effective (a technique seen in recent years in Syria). The Baden-Powell sketch was then used as a basis for this image below, which also shows on the right an ingenious “dummy” to draw fire.

In one of those odd parallels, you may recall that I wrote about an improvised artillery piece used during the Boxer rebellion (1899) here, that had been dug up in a garden. Well there was also an improvised artillery piece art Mafeking also used in 1899. It too was dug up in a garden It is described here by Baden-Powell himself:

The third gun was one which Mr. Rowlands dug up from his garden: an old muzzle-loading ship’s gun with a history. We had it cleaned up, sighted, and mounted on a carriage, and it did right good work. Owing to its ancient Naval connection the gun was named ‘Lord Nelson.’ It was made in 1770 and weighted 8 cwt. 2 qrs. 10 lbs. These figures 8.2.10 were inscribed upon it and led some people to suppose it was made on February 8, 1810. It also had the initials ‘B. P.’ Upon it, which might have led such people further to suppose that it belonged to me in former times. It didn’t really; those initials stood for Bailey, Pegg & Co., the makers, of Brierley Foundry, Staffordshire. The absence of the Royal Cypher showed that it had not been a Royal Navy gun but belonged to a privateer. According to local tradition two Germans brought it to Linchwe, a neighbouring chief, some forty years ago, and he sold it to the Baralongs for twenty-two oxen, to aid them in their defence against Boer freebooters. It fired a 10-lb. shot, and carried 2,000 yards, though not with great accuracy. We found its sister-gun in Rustenburg, where in 1881 it had been used by the Boers to shell the British defence works. And a third gun of the same family was found by General Burn-Murdoch near Vryheid; while a fourth stands, I believe, at Brierley Hill, having been presented to the town by the makers.

How extraordinary that in two sieges in separate parts of the world, at the same time, they both used ancient cannon dug up from a garden.

Other artillery pieces were entirely improvised, here described by Baden-Powell again:

Our great gun was our home-made one, ‘The Wolf’ (my nickname from Matabeleland). This was made from a steampipe round which were lapped iron rods which were welded and turned till a good strong barrel was made. The breech and trunnions were bronze castings. The whole was built up by the railway workmen under Mr. Coghlan, the energetic and ingenious foreman, and under the general supervision of Major Panzera. The blast furnace for making the castings alone was a triumph of ingenuity made out of a water-tank lined with firebricks — the blast being introduced through a vacuum brake tube.

The “Wolf” is now held by the Royal Artillery Museum, due to open later this year.

The Boers sent a trolley loaded with dynamite rolling down the railway into Mafeking, but it luckily exploded before reaching us — about a mile outside.