This history of looking at IEDs and IED incidents for technical intelligence is interesting and goes back quite a way – certainly as far as the late 1500’s when Elizabethan spy master Francis Walsingham engaged Giambelli, the IED maker who made the Hellburner hoop – (Walsingham calls him “Jenibell” but there is no doubting it is the same person)

Stories of the British WTI investigations of Russian sea mine IEDs are here, and I have a stack of stuff on Colonel Majendie’s quite excellent WIT reports from the 1880s to discuss in future blogs. For now though, here’s a very early US WIT report from 1860, by Major Richard Delafield. He is reporting on a Russian IED encountered by the British four years earlier in 1856.

As the British and French fought the Russians in Crimea, there was significant interest in the US military about how warfare was developing given the technological advances in weapons and tactics used by both sides in the Crimea. In 1855 Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, created a team called “The Military Commission to the Theater of War in Europe”. The team consisted of three officers – Major Richard Delafield, (engineering), Major Alfred Mordecai (ordnance) and Captain George B McClellan of later civil war fame. McClellan resigned in 1857 and the report was published in 1860. It is wonderfully detailed and I’d recommend it to any students of military history – it covers just about all aspects of European military developments, from defensive positions, artillery to mobile automated bakeries aboard ship, ambulance design, hospital design and French military cooking techniques.

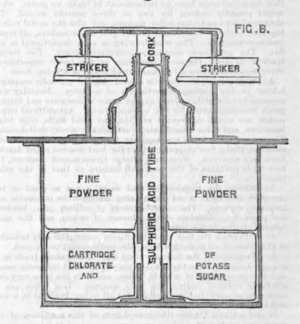

In the Crimean War the Russians protected their elaborately engineered defences with “fougasse” explosive charges – nothing new there, because as a tactic this is as old as gunpowder itself. Until the Crimea these fougasses had to be initiated by an observer, i.e. command detonated by burning fuze or the newly invented concept of electrical initiation. However the Russians had a new technique to deploy. Immanuel Nobel (father of Alfred Nobel) had been engaged by a Russian military engineer, Professor Jacobi to develop submarine charges and a contact fuzing system. These “Jacobi” fuzes consisted of a pencil sized glass tube filled with sulphuric acid fastened over a chemical mix. Some reference history books say the chemical mix was potassium and sugar but I think that’s probably a misunderstanding – I would suspect the mix was actually either potassium permanganate and sugar or potassium chlorate and sugar, as in Delafield’s report below. This explodes initiating a gunpowder charge sealed in a zinc box. One might have expected Mordecai to take an interest in the IEDs but it was Delafield who took particular interest and heartily recommended the use of such things by the US military. Here is an extract from Delafield’s “WIT” report from the device recovered to the British “CEXC:”:

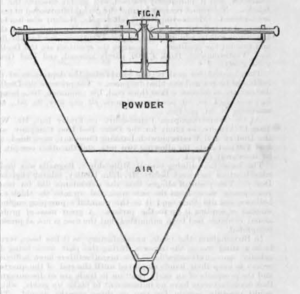

They consisted of a box of powder eight inches cube (a), contained within another box, leaving a space of two inches between the, filled with pitch, rendering the inner box secure from wet and moisture, when buried under ground. The top of the exterior box was placed about eight inches below the surface, and upon it rested a piece of board of six inches wide, twelve inches long and one inch thick, resting on four legs of thin sheet iron (o), apparently pieces of old hoops, about four inches long. The top of this piece of board was near the surface of the earth covered slightly, so as not to be perceived. On any slight pressure upon the board, such as a man treading upon it, the thin iron supports yielded. When the board came into contact with a glass tube (n) containing sulphuric acid, breaking it and liberating the acid, which diffused within the box, coming into contact with chloride of potassa (sic) , causing instant combustion and as a consequence explosion of the powder.

Crimean victim operated IED

Delafield goes on to note that the British and French exploiting these devices did not have a chemistry lab available to properly identify the explosives.

A second device is then described:

Another arrangement, found at Sebastopol, was by placing the acid within a glass tube of the succeeding dimensions and form. This glass was placed within a tin tube, as in the following figure, which rested upon the powder box, on its two supports, a, b, at the ends. The tin tube opens downwards into the powder box, with a branch (e) somewhat longer than the supports, (a, b) This , as in the case of the preceding arrangement, was buried in the ground, leaving the tin tube so near the surface that a man’s foot, or other disturbing cause, bending it, would break the glass within, liberating the acid, which, escaping through the opening of the tin into the box, came into contact with the potassa, or whatever may have been the priming, and by its combustion instantly exploded the powder in the box. What I call a tin tube, I incline to believe, was some more ductile metal, that would bend without breaking. For this information I am indebted to the kindness of an English artillery officer who loaned me one in his possession and from which measurements were made.

Sebastopol IED

This last sentence has the hairs on the back of my neck standing up – because I know that the famous Colonel Majendie, who later became the British Chief Inspector of Explosives and who conducted remarkable IED and WIT investigations some 30 years later, fought as a young artillery officer at Sebastopol. Could it be the same man? I’d like to think so.

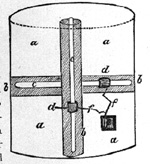

Later in the report is some intriguing details of electrical initiators for explosives, including the use (in 1854 )of mercury fulminate.

I’m also on the hunt for a report I know exists of a US investigation into Chinese Command initiated river mine IEDs from the Boxer rebellion in 1900. When I get it I’ll post details.