In my previous post I discussed Russian stay-behind explosive devices . Now, it is usually my habit to dig back in history to find earlier instances of certain attack styles, and indeed this does apply in this case. I’ve written a little before about Russian mines in the Crimea during the war with the French and British in the 1850s. When the Russians lost Sebastopol to the British and French in 1855, they “left behind” numerous booby-trapped explosive devices hidden in the buildings and connected, in some cases, to powder magazines within the fortresses of Sebastopol. So these were massive IEDs, left behind within potential military facilities, by the Russians. so in some ways exactly the same concept of operations as the WW2 F-10 devices, except the latter were command detonated rather than victim-operated.

Here’s a report from a “war artist” who was on the scene of one of the explosions:

Yesterday, as I was sketching in the west of Sebastopol, an explosion shook the buildings around and reverberated through the roofless and untenanted edifices of the place. The Arsenal Creek was filled with a heavy black smoke, and showers of large stones fell into the water, lashing it for a moment into sheets of foam. The centre of the fire was a battery on the left flank of the Creek Battery. This was one of the works erected by the Russians to sweep the approaches of the Woronzoff road; it was built of stones taken from the houses around it, faced with earth externally, and without a ditch. The magazine was in the foundations of a house which had once stood there […]. The Russians had placed a fougasse over it, and an accidental tread upon a wooden peg driven into the earth broke a glass tube of inflammable matter which communicated with the powder below […].

Three of the men in the work were blown to atoms; and a large number were buried in the ruins; whilst sad havoc was at the same time committed on parties of workmen leading mules along the road close by. Two soldiers of the guard in the Creek Battery were killed by stones projected with great violence into the air, and launched with fatal force upon them. Several mules and horses were killed in this same manner, and every point within 200 yards of the spot was visited by the terrible shower. The crater left by the explosion was about twenty feet deep and twenty wide; and in its crumbled sides were found some of the wounded, who were speedily conveyed to hospital.

So for the victors in urban environments, the challenge of stay behind devices goes back a long way. I contend that there are direct similarities in the concept of operations between the Russian stay-behind devices in the Crimea in 1855 and those of 1941 and the Eastern Front. I wonder too about those towns in Iraq and Syria, liberated from ISIS/Daesh and the identical challenge faced by EOD teams this very day and for years to come. Nothing in EOD is new.

From the description above it’s clear that these were versions of the Jacobi-Fused landmines used elsewhere in defensive positions by the Russians.

The fact we know a fair amount about these mines is in part due to a US military mission to the Crimea. In 1855 Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, created a team called “The Military Commission to the Theater of War in Europe”. The team consisted of three officers – Major Richard Delafield, (engineering), Major Alfred Mordecai (ordnance) and Captain George B McClellan of later US Civil War fame. McClellan resigned in 1857 and the report was published in 1860. It is wonderfully detailed and I’d recommend it to any students of military history – it covers just about all aspects of European military developments, from defensive positions, artillery to mobile automated bakeries aboard ship, ambulance design, hospital design and French military cooking techniques.

With regard to innovative munitions, Immanuel Nobel (father of Alfred Nobel) had been engaged by a Russian military engineer, Professor Jacobi, to develop submarine charges and a contact fuzing system. These “Jacobi” fuzes consisted of a pencil sized glass tube filled with sulphuric acid fastened over a chemical mix. Some reference history books say the chemical mix was potassium and sugar but I think that’s probably a misunderstanding – I would suspect the mix was actually potassium chlorate and sugar, as in Delafield’s report below. When the glass vial contianing the acid is broken, (such as when stood upon) it mixes with the chemicals below and explodes initiating a gunpowder charge sealed in a zinc box. One might have expected Mordecai to take an interest in the IEDs but it was Delafield who took particular interest and heartily recommended the use of such things by the US military. Here is an extract from Delafield’s technical report from the device recovered by the British:

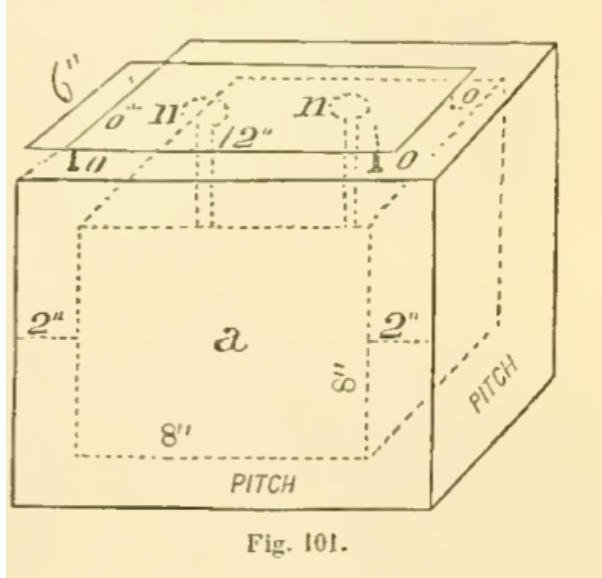

They consisted of a box of powder eight inches cube (a), contained within another box, leaving a space of two inches between the, filled with pitch, rendering the inner box secure from wet and moisture, when buried under ground. The top of the exterior box was placed about eight inches below the surface, and upon it rested a piece of board of six inches wide, twelve inches long and one inch thick, resting on four legs of thin sheet iron (o), apparently pieces of old hoops, about four inches long. The top of this piece of board was near the surface of the earth covered slightly, so as not to be perceived. On any slight pressure upon the board, such as a man treading upon it, the thin iron supports yielded. When the board came into contact with a glass tube (n) containing sulphuric acid, breaking it and liberating the acid, which diffused within the box, coming into contact with chloride of potassa (sic) , causing instant combustion and as a consequence explosion of the powder.

Delafield goes on to note that the British and French exploiting these devices did not have a chemistry lab available to properly identify the explosives. I think a mention of a lack of resources for what today might be called “Tech Int” is instructive! The deployment of Technical Intelligence laboratories and associated “CEXC” capabilities to theatres remains an issue today.

A second device is then described:

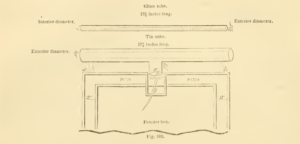

Another arrangement, found at Sebastopol, was by placing the acid within a glass tube of the succeeding dimensions and form. This glass was placed within a tin tube, as in the following figure, which rested upon the powder box, on its two supports, a, b, at the ends. The tin tube opens downwards into the powder box, with a branch (e) somewhat longer than the supports, (a, b) This , as in the case of the preceding arrangement, was buried in the ground, leaving the tin tube so near the surface that a man’s foot, or other disturbing cause, bending it, would break the glass within, liberating the acid, which, escaping through the opening of the tin into the box, came into contact with the potassa, or whatever may have been the priming, and by its combustion instantly exploded the powder in the box. What I call a tin tube, I incline to believe, was some more ductile metal, that would bend without breaking. For this information I am indebted to the kindness of an English artillery officer who loaned me one in his possession and from which measurements were made.

The famous Colonel Majendie, who later became the British Chief Inspector of Explosives, the UK first official bomb disposal officer, and who conducted remarkable IED and technical investigations some 30 years later, in the 1880s, fought as a young artillery officer at Sebastopol. Could it be the same man? I’d like to think so.

The Jacobi fuse , or at least a variant of it, was used in Russian sea mines at the time – see this earlier post.

But of course one can go back further in time to look at previous Russian efforts, earlier still. When Napoleon’s Grande Armee entered Moscow in 1812, it was with great triumph and the summit of a remarkable campaign – but within a day Russian saboteurs had started to burn the city to make it uninhabitable for the occupants. Napoleon himself had to be rescued from fires encroaching the Kremlin and soon the retreat from Moscow started. I don’t doubt that the Russians of 1855 and 1941 knew their history. and whether it is a knowledge of history, or something else, the ruins of Syria and Iraq today pose an identical challenge. Moscow 1812, Sebastopol, 1855, Kiev and Kharkov 194, and Syria 2019.

Here’s a pic of Moscow burning, set fire by Russian saboteurs, with Napoleon looking glumly on.

Update:

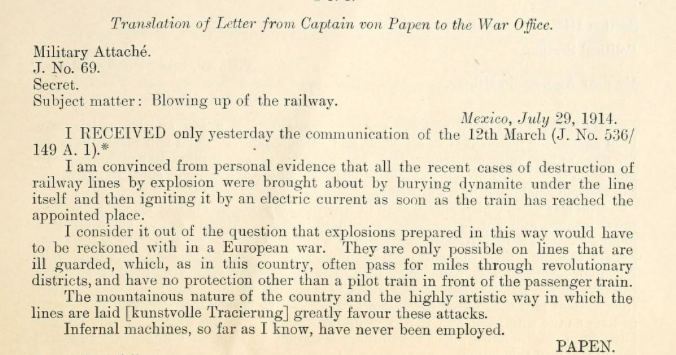

I’ve been asked for a bit of clarity on the Russian mines discussed by Delafield and the “Jacobi fuzes”.

So, Jacobi fuzes were designed by Immanuel Nobel, and were fitted to a range of munitions. The fundamental principle behind the fuze is a glass vial of sulphuric acid held above a potassium chlorate (or potassium chlorate and sugar) mix. Some action or other on the munition breaks the glass vial, which then allows the sulphuric acid to mix with the chlorate. this generates enough energy to ignite a powder train to the main charge. In the sea mines encountered by the British Navy in the Baltic during the Crimean war there were steel springs and rods which broke the glass when a ship touched the moored mine. In the Crimea itself and these devices above then it was the action of a person stepping on a plate which in turn caused the glass to break.

Delafield’s diagrams, (Fig 101 and 102) respectfully, are indeed not that clear. But there are two different mechanisms, both pressure from above in each device which cause the glass to be broken. The “pitch” mentioned is simply a method to seal the box containing a volume of gunpowder from the ingress of water from the ground in which it is buried, giving the “mines” a longevity. If you wish you can read the original “technical intelligence report” at this link here.