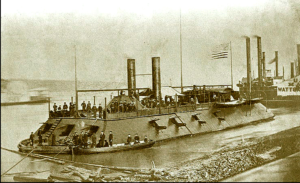

The USS Cairo was a quite magnificent gunboat, part of the Union fleet in the American civil war that operated on the Mississippi and its tributaries. She was built in 1861 and in January 1862 became part of the Union Army’s Western Gunboat Fleet and then in October 1862 was handed to US Navy ten weeks prior to the incident described below.

Please note that there are several versions of this story, some of them contradictory. I’ve dug quite deeply through a number of sources including Official Naval Records, to summarize key aspects, and highlight some interesting questions.

In December 1862 the Cairo became the first gunboat to be sunk, according to Union forces, by an electrically initiated under water mine, in combat. The Cairo headed a small flotilla of four boats tasked to clear the Yazoo river, a tributary of the Mississippi. The commander of the Cairo, LTC Thomas Selfridge, was tasked with conducting a complex operation to clear the Yazoo of explosive devices. A few miles upstream of where the Yazoo meets the Mississippi the flotilla encountered an area where Confederates had placed a number of under-water mines.

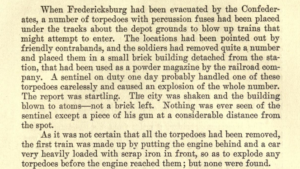

The flotilla’s EOD technique is worthy of some analysis. It appears they pushed forward the shallow draft boats along the banks. These were tasked with looking for evidence of the mines underwater (some of the floatation elements of the devices were apparently visible, suggesting poor emplacing technique) and more importantly looking for the ropes that led from the bank to an anchor under the mine, and by which the Confederate forces could raise or lower the mine in the water. Render safe procedure then involved shooting at the mines in the water (not an hugely effective technique I would suggest), or releasing the anchor ropes and pulling the mines in to the shore where they were dismantled. Bearing in mind that the devices could have been command initiated, then this should have required clearance on foot up the banks of the river by a well supported ground unit, and that the mines could have been movement sensitive, then careful stand off and remote hook and line technique would be required, it is not clear that either aspect of the IED threat had been fully thought through by the flotilla, given the reports available. However I may be applying 20/20 hindsight of modern IEDD theory.

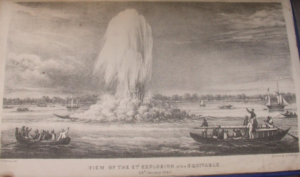

The flotilla had found and made safe five of the mines when it appears that one of the boats started firing at what they thought was a floating torpedo. Selfridge, on the Cairo went forward to assist. It was at this point that an explosive charge detonated on the port bow of the Cairo. According to Selfridge there were two explosions, one shortly after the first. A large hole was blown in the bow of the Cairo. The crew were rescued but the Cairo sank in 30ft of water in about 10 minutes.

Eventually all that was left was the two smokestacks and flagpoles protruding from the water – these were removed to prevent Confederate forces identifying the spot and salvaging the big guns. The location of the Cairo was then forgotten in history until it was found in the 1960s, raised and renovated as a museum piece.

Most press reports and personal reports of the time suggest the explosive was electrically initiated. But that may not be the case. Time for some detective work, which involved looking at other sources, including official naval records which provides a fairly hasty investigation by Selfridges commander, Rear Admiral Porter. Certainly such electrical initiation technology existed and was used by Confederate forces, notably on the James River and at Columbus, Kentucky. I then found an excellent book “The sinking of the USS Cairo” by John Wideman who has gone much deeper into this investigation and exposed a fascinating legal process undertaken by the Confederate perpetrators to claim ownership of the underwater mine design.

Firstly in Brigadier Gabriel Rains’s documents, (Rains being the leading designer of explosive “torpedoes” for the Confederates and head of the secret Confederate Torpedo Bureau), he suggests the device was a “demijohn torpedo” and his description of the manufacture of demijohn torpedoes makes clear that it was a movement sensitive initiation switch, which functioned as the charge was tilted – which fits the description of the device functioning as it touched the port bow of the Cairo. Rains’s device used an inverted demijohn, which had a 6lb ball of metal in the recess at the base of the demijohn. When the charge was disturbed the weight falls off the indentation at the base of the inverted bottle and pulls a striker mechanism. A full description of its construction and operation is in the re-print of Rain’s book, page 37. These demijohn mines could contain 50lbs of explosives. The Rains’s description is given added credibility as he even names the Confederate officer (Capt Zere McDaniel) who emplaced it. Perhaps the assessment by Union forces of the electrical initiation was used to lessen the blame on Selfridge and his EOD operators who perhaps had carried out the incorrect EOD drill for dealing with this design of infernal machine? However an alternate source suggests that McDaniel had been trained by a confederate officer, Lt Beverley Kennon, who had developed an electrical initiation system. A full description of its construction and operation is in the re-print of Rain’s book, page 37. The key thing here, however is that the EOD technique of dragging the mines to the shore would have caused them to initiate… and the EOD troops had successfully dealt with 5 devices without a detonation when the attack occurred. So I’m going to rule out a Rains design for the demijohn mine.

The second alternative is based on other reporting. This reporting suggests that Zere (or Zedekiah) McDaniel, along with a Francis A Ewing, members of the Confederate Submarine Battery service, were busy manufacturing torpedoes up river in Yazoo City. They obtained their demijohns from Yazoo city merchants and begged for powder from Confederate artillery units. According to one report the devices were pull initiated using friction primers pulled by “wire”. Those artillery units would have also been equipped with friction “pull” primers, which makes me inclined to think these devices could indeed be pull initiated. If I were responsible for laying and operating such a device, frankly such a mechanism would appeal to me as being probably safer to emplace, and more reliable to use than a new fangled electrical method. If McDaniel was begging for demi-johns and begging for support from artillery units, it would appear he was under-resourced, and “making do”. Porter’s investigation suggests wire to the banks were found and cut but I think he is making an assumption that the wires were electrical, as we know of reports that McDaniel was using wire as a pull mechanism. Porter’s report and judgement on Selfridge is here.

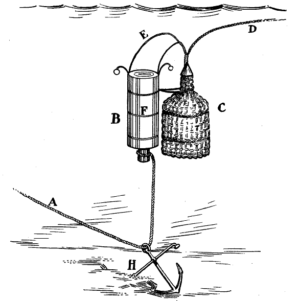

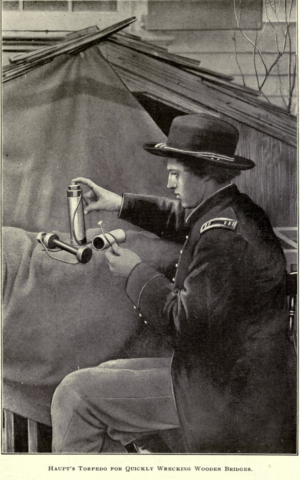

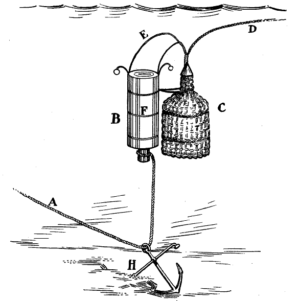

Of particular note is that the commander of another gunboat, Lt Hoel, of the Pittsburg was ordered to sweep the banks for evidence of the initiation mechanism. He did so but only reported magazines and material from which the torpedoes were manufactured, and makes no mention of any galvanic batteries. Here’s a diagram provided by one of the officers responsible, Fentress, found in the Official Naval records. This is interesting, because it shows the demijohn vertical rather than inverted as in Rains’s design. Note that the diagram shows “wires” at (D) but these could just as easily be pull wires rather than electrical wires. However I think we should take Fentress’s diagram with caution as it doesn’t really make sense, and misjudges the issue of floatation and negative buoyancy.

Wideman in his book has found some remarkable documents which include affidavits from McDaniel and Weldon regarding the design of the torpedoes, their claim for “ownership” of the design and their operations on the Yazoo river. Indeed another man, Francis Ewing also claimed responsibility for the design, and each pursued those claims in the hope of a secret bounty from the Confederate Government.

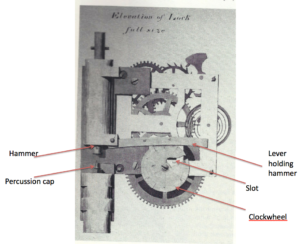

The more I find out about McDaniel the more interesting his story becomes. McDaniel was a Kentucky born engineer, who lost an arm while fighting with the Raymond Fencibles (the 12th Mississippi Regiment.) He fought on for a while with a specially rigged Maynard carbine, despite the loss of his arm. He then came up with ideas relating to submarine mines and won support from those in authority on the Confederate side. Working in the Mississippi backwaters he sickened from malaria, but continued his work. It would appear that McDaniels first designs (which failed) used a pull mechanism to a gun trigger and percussion cap mounted in a box on the top of the explosive charge. McDaniel was then provided with friction primers by Weldon, who himself procured tham from the Confederate artillery unit stationed a few miles upstream. Wideman has found a specific description of the improvised explosive device by one of McDaniel’s torpedo crew. I won’t steal Wideman’s thunder – buy the book!

So, all in all I’m inclined to support Wideman’s research to think that “simplicity” wins out and that these were “pull switch” devices, and not electrical devices, or even “Rains” demi-john designs. This is corroborated by the most important evidence, in my view, a letter from McDaniel to his sponsor, Governor Pettus where he talks of the Cairo which “came into contact with a torpedo made to explode by striking & which exploded and tore the boat fearfully” It seems that the mines could have been placed in pairs with a wire lanyard running between the two – thus any gunboat passing between them or getting caught in the link wire would cause the mines to initiate – but the EOD technique used by union forces would have caused detonation rather than recovery. In piecing all this together it is clear (I think) that there were a mix of command initiated pull devices, and pairs of booby trapped mines, also working on a linked pull primers.

A total of 22 union vessels were sunk by Confederate infernal machines during the Civil war and a number of others were damaged.

As for McDaniel, he went on to manufacture and deploy a number of submarine devices for the Confederates in a number of places. in June 1863 he destroyed two Union trains by blowing them up with an ingenious trigger system, while operating behind enemy lines – tales for a future blog post, as is the remarkable bounty enacted by the Confederate Congress for using infernal machines to destroy Union targets. Watch this space.