Follow this link here, to a post I have put on another site, but which readers of this blog with an EOD or ECM background I think will find interesting.

Follow this link here, to a post I have put on another site, but which readers of this blog with an EOD or ECM background I think will find interesting.

There’s been discussion on the letters pages of “The Times” about the origins of the “Tommy Atkins” reference – the standard typical British soldier with all the phlegmatic character so well described by Kipling. Well, it turns out that Kipling didn’t “invent” the name out of the blue, and the history of Tommy Atkins as a real person is moving, dramatic and a little older.

In 1843, The Duke of Wellington, a national hero, former Prime Minister and Victor of Waterloo was a “Minister without Portfolio”. He was an elderly man of 73 and the Grand Old Man of the British establishment. The previous year he had been re-appointed as Commander in Chief of the Army.

The Duke of Wellington, aged 74

Officers on the Army Staff came to show him a new piece of bureaucracy – a form that soldiers had to sign to claim their allowances. They wanted to create a “typical entry” as a guide for soldiers entering their details. The discussion turned to the name that the guide should use as its example, and they asked the old General his opinion.

Wellington sat back and thought. He recalled one of his earlier campaigns, in the Low Countries in 1793. After a battle he had come across a gravely wounded solider, lying on the ground. That soldier had served in the Grenadiers for 20 years, could neither read nor write, but was the “best Man-at-Arms in the Regiment”. His name was Thomas Atkins. Atkins was severely wounded, and had begged the stretcher bearers to leave him be, so that he could die in peace. Looking up and seeing the Duke’s concern, the man uttered his last words. “It’s all right, Sir. It’s all in a day’s work.”

Wellington still remembered that experience, 50 years later, and so the name on the form and for every British soldier since became “Thomas Atkins”.

I’m indebted to John C Wideman, author of an excellent and detailed study of US civil war IEDs for information about another ship-borne IED similar to those mentioned in an earlier blog post.

The USS Intrepid was a ketch, originally named the Mastico, captured from Tripoli (now in Libya) in the First Barbary War. The First Barbary War has its origins in interesting parallels with modern piracy.

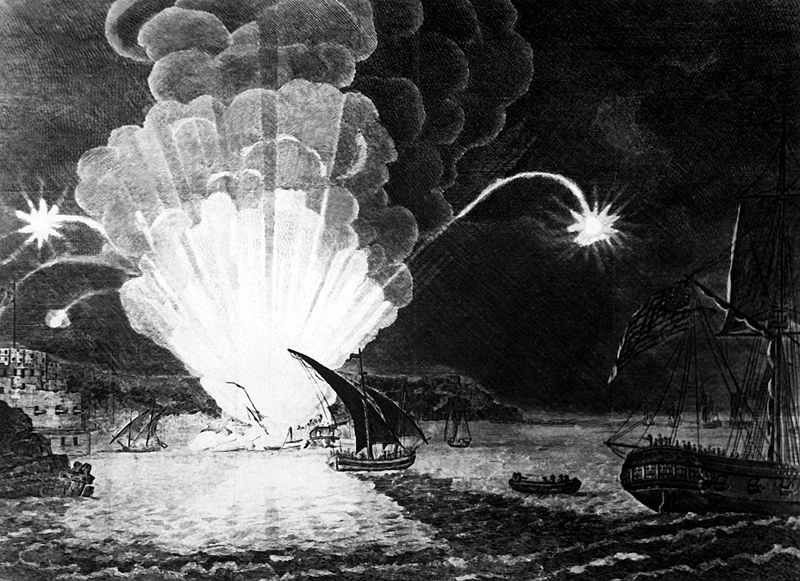

In 1804, the Intrepid was converted into a “floating volcano”, to be sent into Tripoli harbour and blown up amidst the corsair fleet adjacent to the walls of the port’s fortress. The ketch was loaded with 150 artillery shells and 100 barrels of gunpowder. Burning fuzes with a 15 minute delay were attached. a crew of 11, led by Lt Richard Somers manned the vessel. On entering Tripoli harbour, it cane under intense fire, and was unable to manoeuvre towards the intended target. The 15 minute fuze proved unreliable and the ship detonated prematurely, killing the crew who had intended escaping by row boat.

USS Intrepid exploding in Tripoli Harbour

So, it can be seen, the explosively laden ship has been a repeated tactic, since 1584:

1584 – The explosion of the “Hoop”, Antwerp, against the invading Spanish Army. This incident remains, in my opinion the IED that has killed most victims in history, with 800 – 1000 killed. Tell me if I’m wrong.

1693 – The “Vesuvius”, used by the British under Admiral Benbow against St Malo

1694 – The Dieppe Raid, and raids against Dunkirk using the same technique

1804 – The Intrepid used by the American Navy against Tripoli, North Africa

1809 – Two explosive ships used by Admiral Cochrane, against the French, in the Basque Roads. Notably these had 15 minute fuses which exploded prematurely.

1864 – USS Louisiana, used in the US Civil war against Fort Fisher, Wilmington, N Carolina.

1918 – Zeebrugge raid, by the British Navy, using a submarine packed with explosives

1942 – HMS Campbelltown rammed into the dock gates in St Nazaire by the Royal Navy.

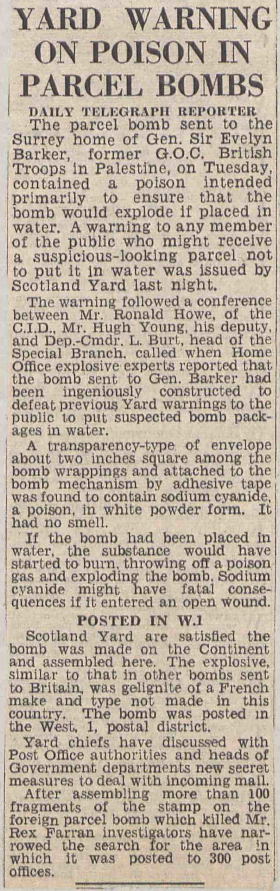

A friend pointed me in the direction of recently declassified MI5 files, now officially and publicly available. One set of hitherto SECRET and TOP SECRET papers relates to a series of attempted IED attacks on British targets in 1947, by the Stern Gang, in the run up to the Israeli declaration of Independence in 1948. If you have the patience, there is an 88Mb download available at this link. For those of you with an interest in technical matters, the report by Her Majesty’s Inspector of Explosives on one device, planted in Dover House, Whitehall, London on 16 April 1947 is on page 239.

The devices largely failed for technical reasons. However later IEDs in 1948 were not all failures.

Elsewhere in the released documents, historians will find some of the material fascinating. MI5 demonstrably retained some of its star security officers from WW2, and they were involved, in part, in this case – people like “TAR” Robertson who ran the “Double Cross” counter intelligence operation against the Nazis in the War.

There’s some fascinating reporting of its time – telephone operators overhearing suspicious conversations, members of the public reporting concerns, police surveillance operations and pre-digital secret bureaucracy. It is interesting to see the 1947 version of inter-agency counter-terrorist coordination between Foreign Office, MI5, police forces, Special Branch and others.

A later file from 1948 is also available for download (post the establishment of the State of Israel) and others clearly can now be accessed. In May 1948 the Stern gang sent a postal IED to Captain Roy Farran of the SAS (who was accused of murdering Alexander Rubowitz) The package (addressed to R Farran), was opened by Roy’s brother Rex, killing him.

Sos Cohen is another of those men from history and whichever way you look at it his story is pretty remarkable. “Sos” is an abbreviation of his nickname “Sausage”. Lionel Frederick William Cohen was born in 1875 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. At the age of about 14 he ran away from home and joined the Royal Marines Light Infantry. (That was his first military engagement.) Eventually he was tracked down by his horrified family who insisted on buying him out and bringing him home.

His family then sent him to work as a clerk for an uncle in Johannesburg. He was bored by that, ran off, and at the age of 17 became a guard for a mining company. Seeking adventure he then joined as a volunteer in the campaign against the Matabele, (his first war) with the now historical figures of Selous and Jamieson. He took part in the Battle of the Shangani River in 1893 where he fought with fixed bayonets. After other adventures in Africa he then became involved in the Boer War in 1899 (War Number 2), where he worked as a undercover special force commander in Mozambique preventing arms being delivered to the Boers, reporting via the Mozambique authorities to his British controllers.

When that war ended he returned to civilian life and had more adventures. When World War 1 (his third war) began he joined the 1st South African Horse as a 2nd Lieutenant. He fought in German East Africa. At one point he and a single troop captured 430 of the enemy. After this, now promoted to a “special service” Captain he took his troop behind enemy lines on intelligence missions. In 1916 he was attached to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) as an airborne observer. He was involved in several skirmishes and crashes. In 1917 he formally joined the British Field Intelligence Force, again working behind enemy lines. He ended the war as a major, with an MC and a DSO and was mentioned in despatches three times.

By 1937 he was living in England and played a key role in setting up the RAF Volunteer reserve. He was commissioned into the RAF as a Pilot officer in 1939, aged 64. WW2 being his fourth war and at least his fourth service. He served was a liaison officer from RAF costal command with the Royal Navy. In this role he flew 70 operational missions as an observer or air gunner. He reached the rank of Wing Commander and took part in bombing action against the Scharnhorst over the port of Brest in 1941, and other missions that sunk U-boats. As a senior officer on liaison he was not meant to fly , but insisted on it. He received the DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross) in 1944, his 70th year. He was mentioned in despatches twice more. He died in 1960 aged 85.

I have omitted a lot of his adventures outside of the services, which are equally extraordinary. You can read about them in his biography “Crowded hours”