This post is a bit of a puzzle, that I may need some help with. I’ve blogged before about the German sabotage campaign on the east Coast of America in 1915 here:

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2013/9/17/kurt-jahnke-the-legendary-german-saboteur.html

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2012/1/22/massive-explosion-in-new-jersey.html

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2013/2/12/booby-trap-ieds-on-the-battlefield-1918.html

And indeed I’ve built up a bit of a presentation on German sabotage in 1915-1917 which I may get round to posting here. In brief summary, German agents either operating out of the German Embassy or operating undercover developed a systematic and effective sabotage campaign to disrupt munitions and other cargoes being shipped to the European Allies of France, Russia and Great Britain, before the US entered the war. There is documentation that certainly 35 ships were firebombed, and an additional 39 suffered suspicious fires. Many sabotage events were downplayed or not reported so the number could be significantly higher. A number of munitions factories in the US attacked. Five US Navy warships suffered fire damage, and the USS Oklahoma and USS New York, two new battleships under construction were almost completely destroyed.

Most of the cargo ships sabotaged in 1915 were attacked with small incendiary devices, the size of a cigar. These contained sulphuric acid in one small compartments separated from picric acid or potassium chlorate, by a copper disc.. The copper disc was dissolved over time (usually several days) and then the sulphuric acid was in contact with the other compound causing a violent ignition. Typically a number of these “cigars” were secreted in the cargoes in a ships hold by stevedores of German or Irish extraction in US East Coast ports. Some devices were made aboard German ships, interned in US ports when the British blockaded them. One in particular, the “SS Friedrich der Grosse” of the NordDeutschland Lloyd line was docked in New York and German agents ferried the devices from the ship to the dock workers to hide on board munitions and cargo ships. Other cigars or “pills” as they saboteurs described them, were made in the laboratory of the designer, Dr Scheele at 1133 Clinton Street, Hoboken, New Jersey.

The “cigars” were to a design develped by a German sympathiser, Dr Scheele, and are reported to have been about 4 inches long. Once initiated they ejected white hot flames from both ends.

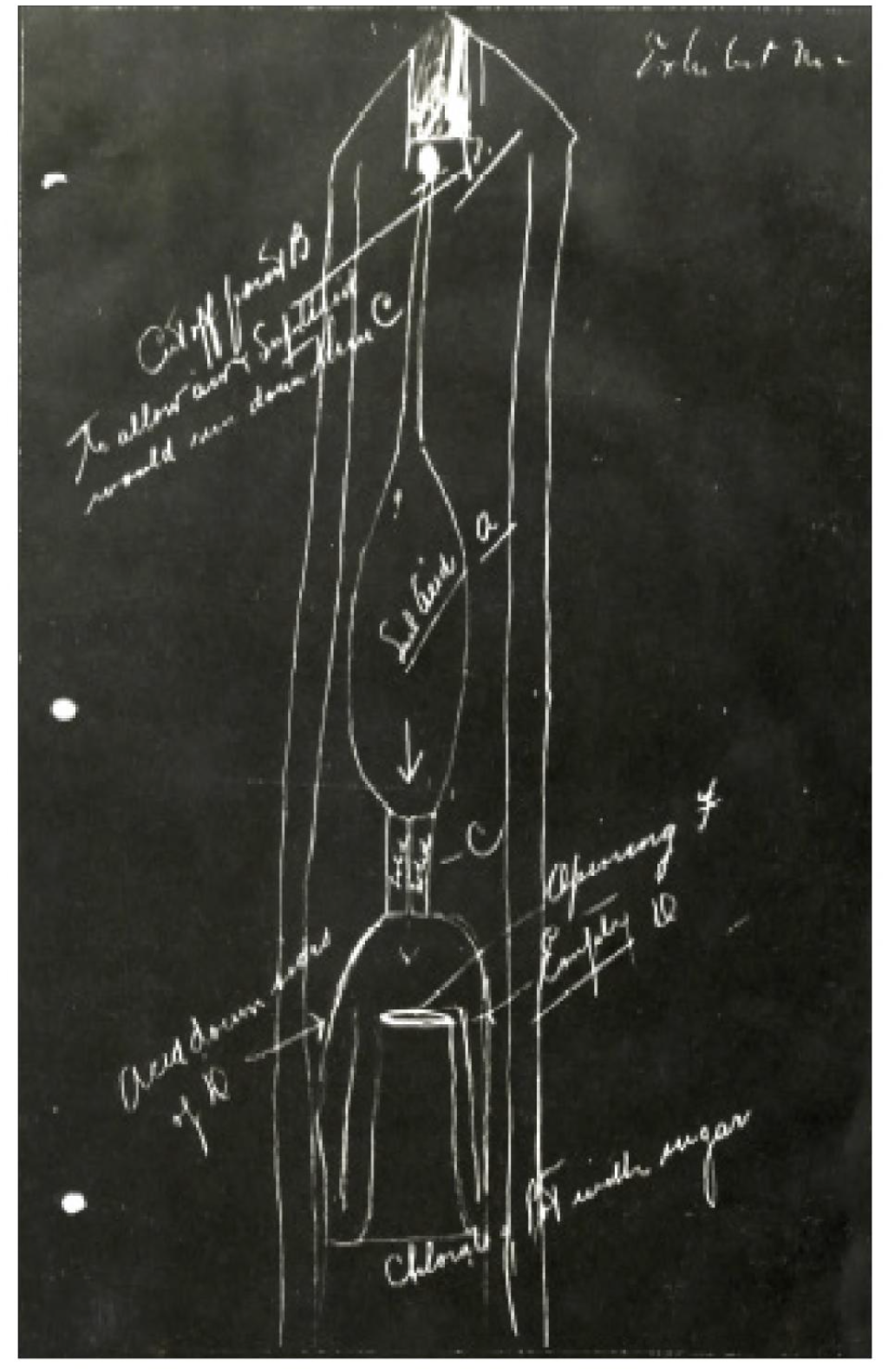

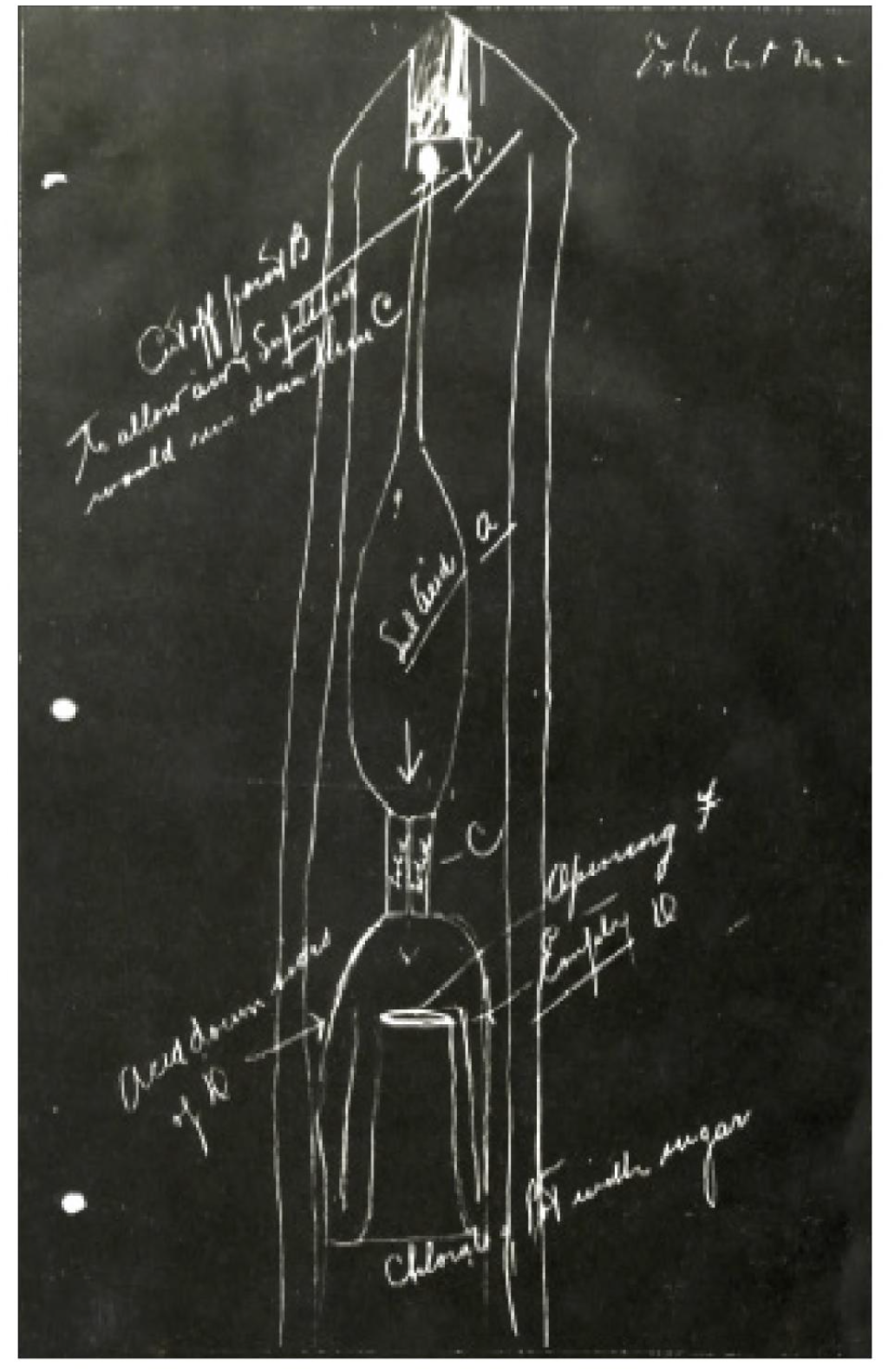

Now, there appears to have been more than one design. In a diagram produced by another saboteur, Frederick Hermann, the construction of the incendiary appears a little more complex, than simply two compartments in a lead pipe separated by a copper disc. It is hard to interpret the diagram below but I note that the compound to which the acid mixes is described as chlorate and sugar, which will make a difference to its explosive effect, depending on relative qunatities of the mixture. The diagram appears (I think) to show an upper reservoir of sulphuric acid, a “neck” halfway down labled “c” (for copper, presumably a copper plug and not a disc), and below that the chlorate with sugar. Wax probably closed both ends.

It should be noted that to work effectively the cigar needs to be positioned vertically, to allow the acid to dissolve the copper and then fall into the chlorate-sugar mix. Only a proportion of the devices functioned and some were recovered by French and British governments in ports in Europe. In 1915 this activity was being led by two officers from the German embassy , Karl Boy-Ed, and Kapitan Franz von Papen. Later in 1915 a secret agent of the German Navy Franz von Rinteln was sent to encouage the sabotage campaign. In a range of investigations led by the head of the NYPD bomb squad, Thomas Tunney, who was seconded to Military Intelligence, the German sabotage cells were largely disrupted. By 1917 the US had entered the war, Rinteln was captured and imprisoned in England and the others had been arrested, expelled or in the case of Dr Scheele, escaped to Havana.

Given that history it was intriguing to find a report on the Australian War Memorial blog about an incendiary device recovered from a ship in 1918, possibly in Liverpool, from a ship arriving from the US. By 1918 most of the German sabotage cells had been rounded up, also the design of the incendiary device is somewhat different.

These images are included on the AWM blog and I’m grateful for their kind permission to reproduce them here.

Working from the photographs alone, it appears that the knurled steel “head” appears to have two openings in it, closed by bolts. I would have perhaps expected only one, to simply fill with acid. The main body appears to be copper and the strange shaped base appears to be aluminium (?), corroded by a galvanic reaction. The base is an odd design. This device, bigger than the earlier cigars would have been more difficult to smuggle aboard and its dimensions would have made it more difficult to conceal in a cargo. The description accompanying the images suggest that rather than acid eating through a reservoir wall in this case the acid ate through a wire which retained a spring action to an initiator…. that’s a quite different initiation mechanism. This device would have taken more skill to construct and the threaded and knurled head, the apparent 3 sections of copper pipe and a neat fitting of the copper pipe to the aluminium base indicates a higher level of engineering…. Something about the base design rings a bell, but I can’t put my finger on it. The design of the base must have a reason and there must be a reason for it to have been different from the copper…but I cant work that out. Any suggestion gratefully received.

The blog from the AWM also has set me off on a new thread. The device appears to have been forwarded to the Australian section of the British “Munitions Inventions Department” in Esher, for examination. The Munitions Inventions Department had been set up earlier in the war to coordinate the wide range of scientific and military engineering developments required by the Allies to win the war. It was really the forerunner of later government defence research departments. Teams of ingenious, pragmatic and capable engineers had been co-opted into developing a wide range of innovative weaponry. By all accounts the Australians were masters of such craft and contributed significantly to a wide range of innovative munitions. I’ve started some research on that and will no doubt blog about some of the wilder and more interesting inventions in the future.

Update on Wednesday, February 3, 2016 at 3:38PM by

Roger Davies

Roger Davies

So a follow up on the mystery device. I have some thoughts beginning to crystallise.

1. I think the corroded base might be Magnesium and not Aluminium. Magnesium would also also be subject to galvanic corrosion (same principle as “sacrificial” corrosion) as it remains in contact with the copper cylinder.

2. In around 1917 German forces developed air dropped incendiaries that used magnesium, dropped by Zeppelins on England. These were impact fuzed, and contained a thermite charge. The thermite then reacted with a magnesium body to cause a fierce fire. Most UK EOD folk will be aware of a further development of these which were used extensively in WW2, and we, the Brits, called them 1kg incendiary bombs. The Germans called them either “Goldschmidt bombs” after the guy who discovered the Thermite reaction, or Elektronbrandebombe or Elektron incendiary bombs, “elektron” being the German name for the magnesium alloy of the body.

3. So.. I think it is possible that this device is a “home made” variant of a German Elektron incendiary. If that is the case then the impact fuse has necessarily been replaced with an acid time fuse, as required in the ship sabotage use-case. Thermite would have been contained in the copper piping, and the magnesium base provided to get the high energy heat, initiated by the thermite reaction. In some of the earlier Zeppelin bombs the body of the core of the bomb was wrapped with rope soaked in tar to give additional burning. This might explain the wide base at the bottom with the tar soaked rope wound around the central core, above the “shelf” provided by the base.

4. Here’s an image of an early incendiary dropped from a Zeppelin (this one is not an elektron bomb, I think).

And here’s one after it is burnt out showing a broad base on which the rope is mounted and a central core:

The design of the magnesium incendiaries evolved quite quickly – here’s what they looked like by the end of WW1 and pretty much through to WW2, with only minor changes:

So… my best guess at the moment is that the device on the AWM site is an improvised incendiary, that may have been wrapped in a tar soaked rope originally and may have contained a thermite charge inside the copper tubing. The base might be magnesium and in the intervening years has galvanically corroded. It will continue to corrode, slowly as it remains in contact with the copper tube. The initiator was a timed mechanism probably using acid to erode a wire, which released a spring allowing a striker to initiate a charge which then ignited the thermite. But I’m far from certain. This means that these later devices, in any event, were much larger than the small 4 inch cigars used in 1915 and therefore harder to smuggle aboard a ship and conceal in the cargo. I’m very open to alternative interpretations.

Update on Thursday, April 14, 2016 at 5:02PM by

Roger Davies

Roger Davies

I have a new update, thanks to the curator at the Australian War Memorial Museum. Following this blog post they tested the base. I had guessed the base might be magnesium, but they found the base material consisted of Copper, Zinc and Manganese. Minor amounts of Arsenic and trace amounts of Titanium, Chlorine and Potassium were also visible.

Back to the drawing board…. Does anyone have any suggestions?

Roger Davies

Roger Davies