An interesting pic below.

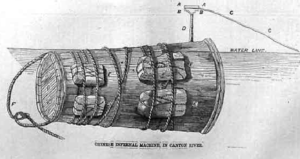

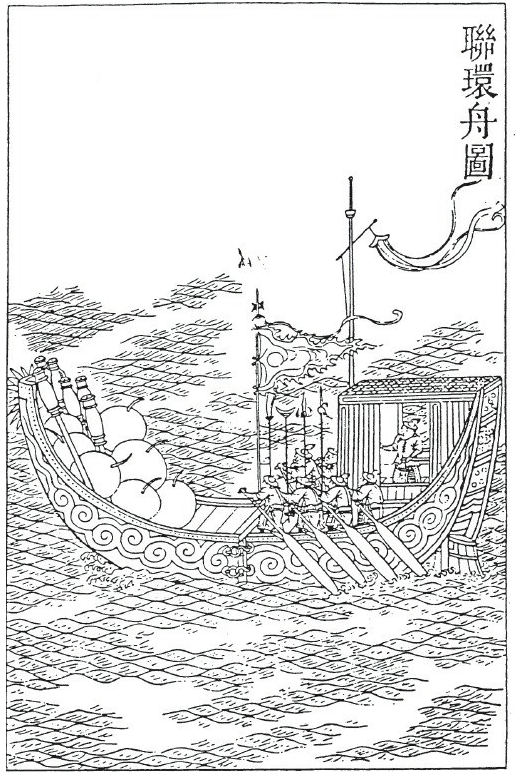

This is from a book written in the mid-1500s by a Chinese Imperial official and shows a sophisticated vessel containing large amounts of explosives. This and other vessels of a similar nature were made at the Dragon River Shipyard near Nanking. There are some interesting features to this:

- Note the bow of the vessel – these protuberances are described as “wolf’s teeth nails”. When the vessel is rammed against the target these steel teeth engage and fasten the bow of the IED vessel to the target.

- Note the “hook and eye connections” amidships. This is pretty clever. After the vessel is rammed into the target the entire “bow” containing the explosives and rockets, is detached by detaching the hooks from the eyes and the attackers row away the foreshortened vessel. Other vessels from the Dragon River Shipyard utilised other designs for leaving behind explosive or combustible material and rowing a smaller boat away – and disguise was a key design consideration. This vessel may have looked like an ordinary commercial vessel with plenty of crew aboard and therefore not like an expected explosive ship, which were usually towed.

- The skipper is protected from enemy weapons in a cabin, and the rowers are equipped with long poles to defend themselves and presumably light the charge.

- The official describes this vessel as being 14m long, with the forward detachable section being about 1/3rd of the length, (so roughly 5m long).

Europeans (specifically the Portuguese) would have encountered these sort of attacks in their war against the Chinese in the first part of the 16th century. So these vessels just preceded the first real European use of this sort of weapon, namely the “Hoop” at Antwerp in 1584. In the early 17th Century the Dutch too faced such weapons in their Chinese adventures. In 1637 a small fleet of English vessels arrived in China to trade and were attacked by a small fleet of fire ships and explosive vessels. The attack was described by a man aboard one of the ships and adventurer called “Peter Mundy”. (That name will make some of you older British EOD types smile). Mundy writes:

“The fire was vehement. Balls of wild fire, rockets and fire arrows flew thick as they passed us, But God be praised, not one of us all was touched.”

Mundy then learned that the attack was actually inspired by the Portuguese in Macao to deter British trade competition. This concept precedes then the development of “spar torpedoes” used frequently in the US Civil war, where an explosive charge was on the end off a spar on the front of an attacking boat, designed to attach to the target.