Last year I wrote two important blog pieces. The first was about the Russian IED expert Ilya Starinov – certainly the most important person in the history of explosive sabotage. The second post was about the Russian F-10 radio controlled demolition device, used successfully by Starinov in WW2.

Since than I have been digging to find more details of Starinov’s devices, which I have finally successfully done, and there are some very interesting findings. I’ve also uncovered other anecdotal stuff about Starinov and indeed about the broader history of IEDs which I’ll post in coming days and weeks. I also have more technical detail on the F-10 to discuss in future posts.

Now, firstly, a caution. Some of the material I have found regarding the construction and design of certain IEDs could be abused by people with ill-intent. All the material I am going to post is unclassified, but I’m going to obscure parts of it and discuss things in some vague terms to make it much less useful to those with criminal intent. If you want to know the source and you know me or can prove you have a legitimate need to see the sources I am using, then get in touch. Otherwise I make no apology for being deliberately non-specific about some of this material. Now, I found the source of this material on line, and others may be able too, but I am going to limit my helpfulness towards those who shouldn’t have this detail. If you want to challenge my assessments and why I draw the conclusions I reach below, I’m very happy to do this off-line. This means, perhaps, you are going to have to trust me on some of my assessments. Or not! Finally I should also point out, sadly, that there is no shortage of detailed technical instructions for miscreants to find how to make bigger and better IEDs then these here discussed in an openly available 70-year-old document, discussing devices from the Eastern Front in 1942. The horse of IED knowledge bolted a long time ago. Close the stable door if you can – I can’t.

The document I found was developed not from Russian sources, but from US sources, who clearly in the immediate post-war period of 1945-1950 had access to German Wehrmacht engineers reports. These engineers had conducted thousands of successful EOD operations. By gleaning reports of Soviet demolition activity, dealt with by the German engineers in WW2, the US military tried to gain a greater understanding of Soviet capabilities in the 1950s. So this was real technical intelligence on Soviet explosive technology, and explosive sabotage tactics, as the Cold War span up. So here we have, in 2020, the opportunity to examine 1950s US military technical intelligence, derived from Nazi German technical intelligence from the period 1940-1945, about Russian explosive devices. So this isn’t exactly a primary source. But some of the detail I’m going to show you makes me convinced this is worthwhile, valuable historical material, and there are certain aspects which surprised me.

Firstly to remind you of the context. It is apparent that the Soviet soldier of WW2 was pretty familiar with improvising explosives charges, either using his own munitions or captured German munitions. The Germans state that the Russian soldier is “particularly ingenious in installing improvised mines and booby traps“. During the latter part of WW2, the Russian use of sabotage explosive devices went way beyond anything seen before or since. Furthermore partisans in Eastern European countries were trained to improvise yet further. Thousands of railway lines, trains and vehicles were attacked explosively by Russians or Russian sponsored partisans in eastern Europe. Much of this was coordinated by Ilya Starinov, who also designed explosive devices , trained the perpetrators and on many occasions planted key devices himself. Starinov survived numerous purges, and went on to develop spetzntaz units and tactics, and taught revolutionaries around the world in the 1950s and 1960s.

In this first post, I’m going to highlight some very interesting similarities between Soviet sabotage devices from WW2 and (get this) IRA devices of the 1970’s, 1980’s and even 1990’s. These similarities go beyond just application of general explosive/sabitage principles – there are significant design similarities in aspects of the devices. Here’s some examples, and a final, highly technical device that I won’t comment on too deeply.

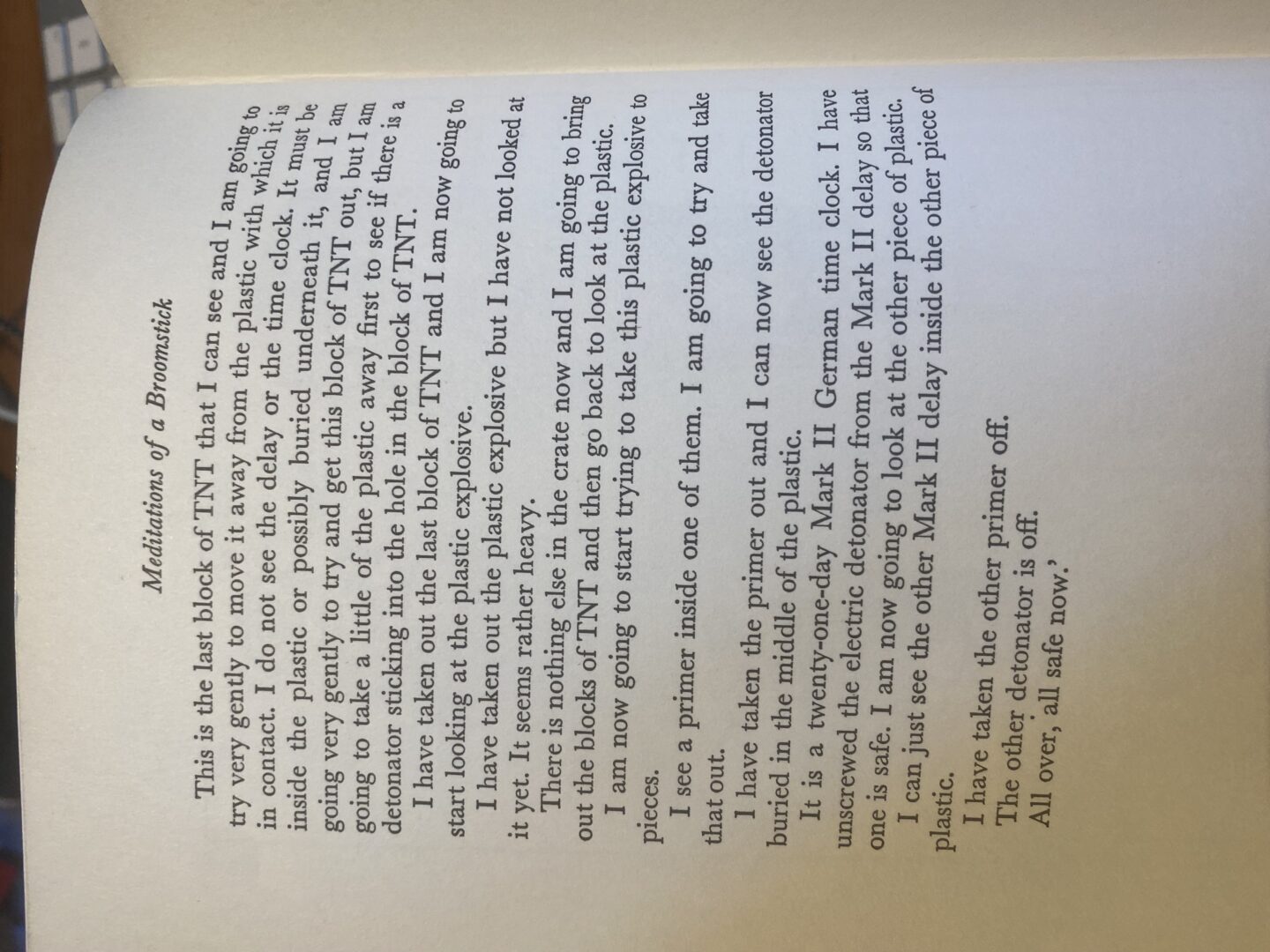

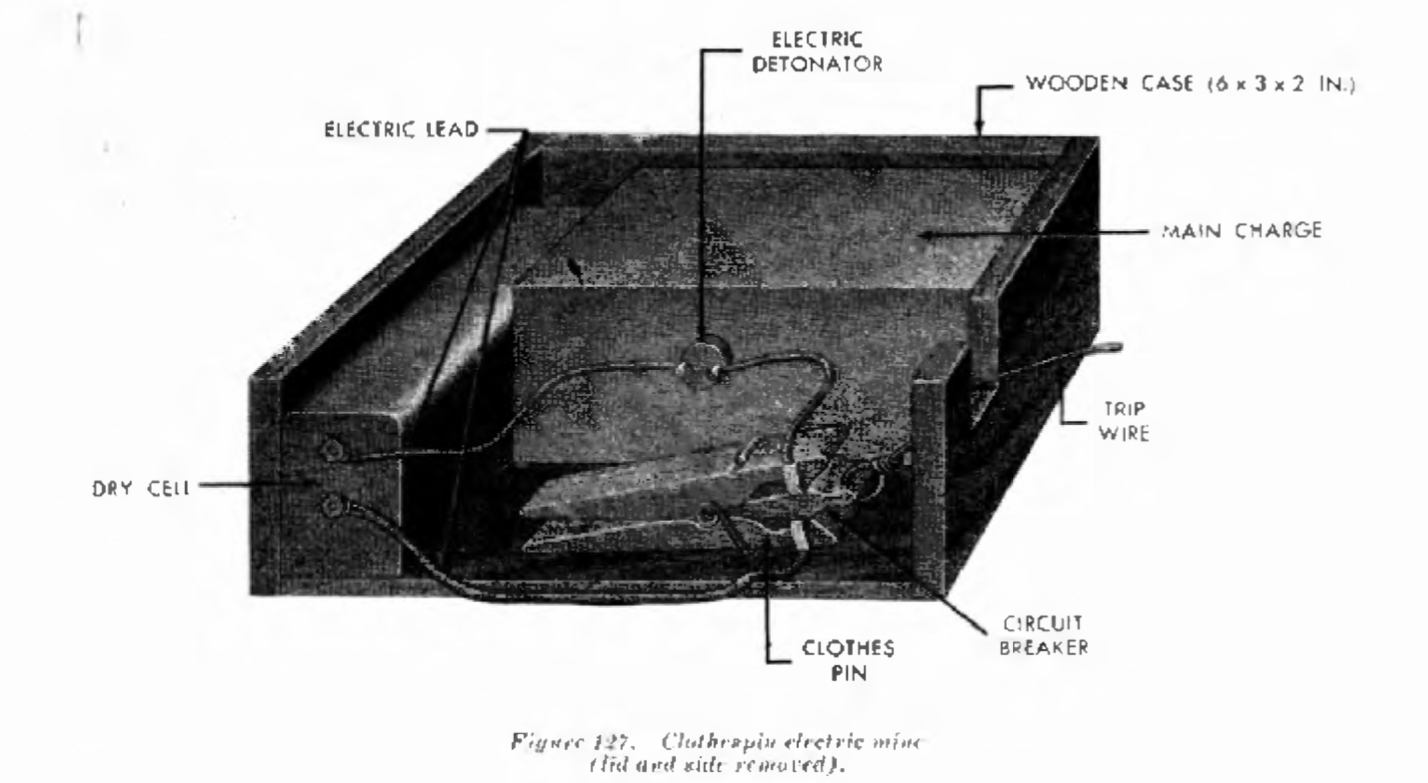

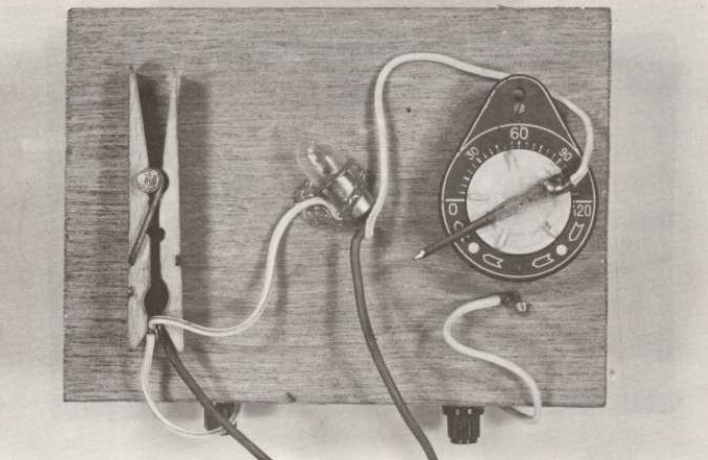

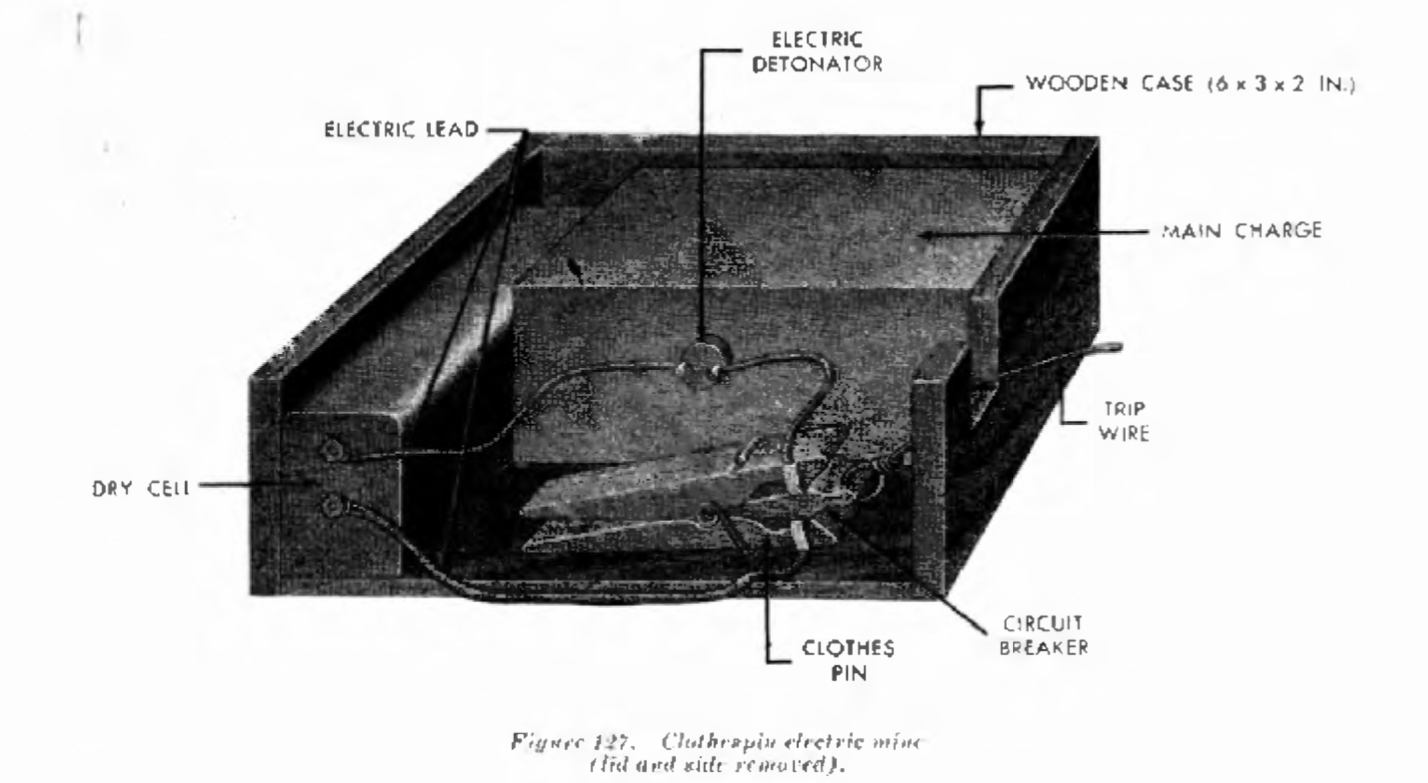

- Firstly there is the use of specific component items. In the 1970s and into the 1990s, many PIRA devices encountered in the UK had firing or arming switches as part of the circuitry. In the vast majority of cases, in what was termed “Time and Power Units” (TPUs) this switch consisted of an adapted wooden springed clothes peg help open with a wooden dowel. Here’s a demonstration circuit showing the “IRA technique”.

- The clothes peg was wired so that a switch closed when an insulator was removed from the jaws of the peg, arming this device. In the 1950 document I have found. German engineers describe this exact concept being found in Russian devices in the early 1940s. Here’s a pic:

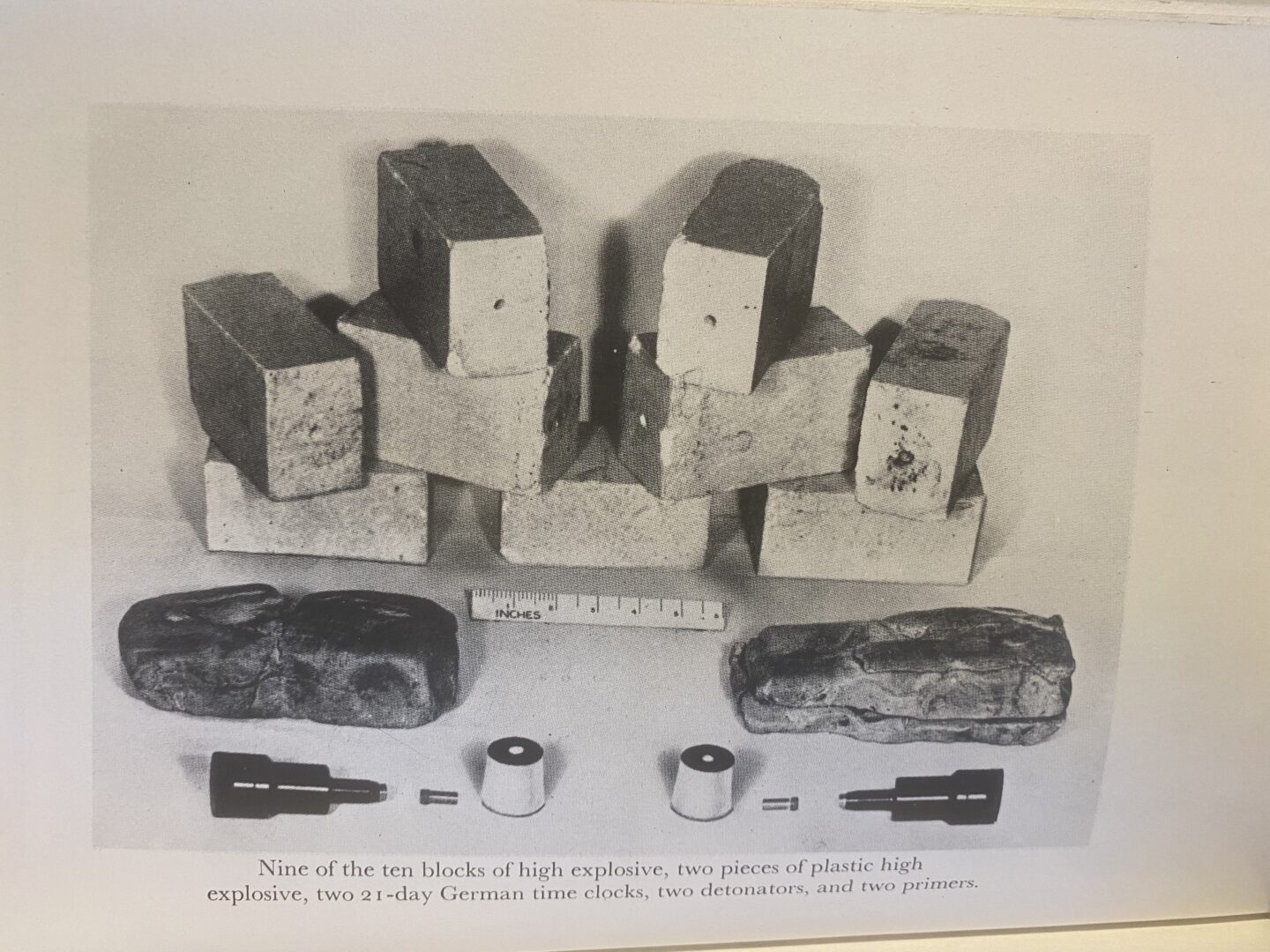

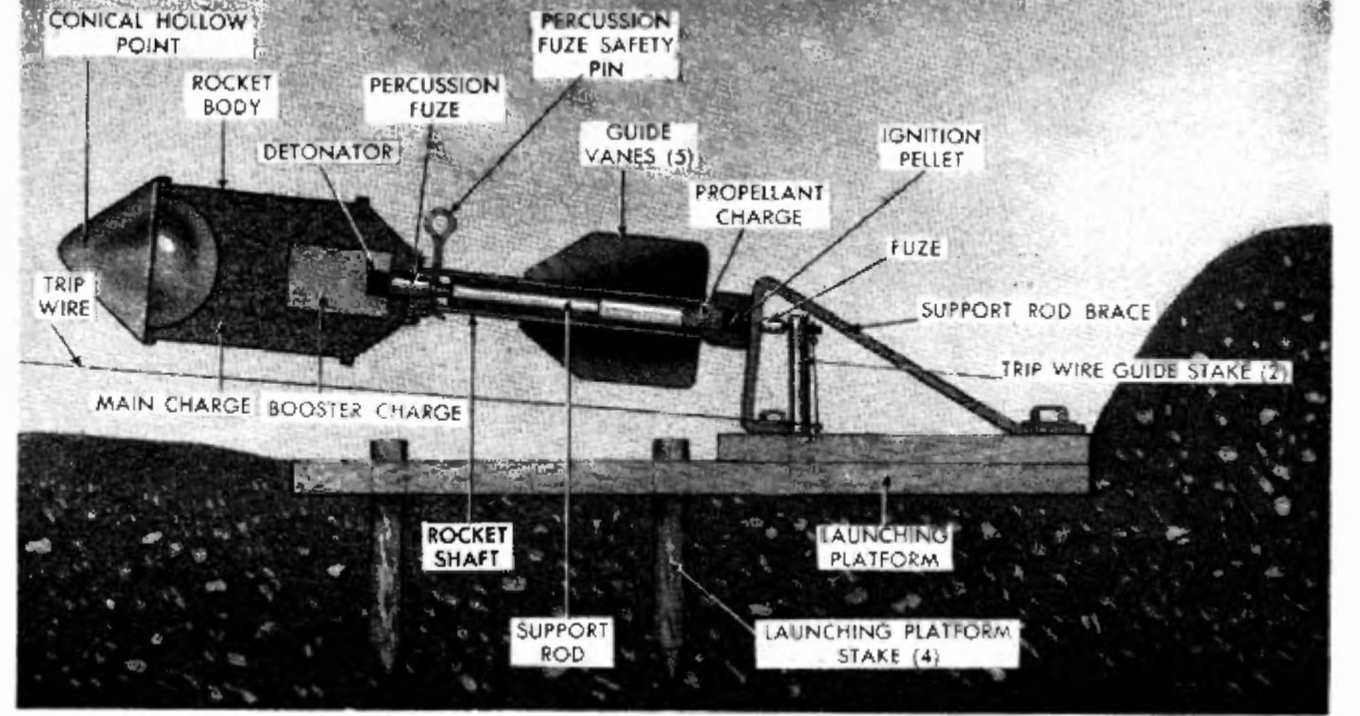

3. In the late 1980s, PIRA developed the “Mk 12” mortar as British Forces called it. This was followed in 1993 by the smaller “Mk16” Mortar. These were missiles that had a shaped charge in its front end, a hollow pipe behind it containing a fuze and tail fins to stabilise in flight. This wasn’t really a mortar but a horizontally fired missile typically fired at vehicles. It had a shaped charge warhead and a fuze set in the hollow tube behind, with simple fns to stabilise it in its short flight. Here’s a picture of a PIRA Mk 12 Mortar. disassembled:

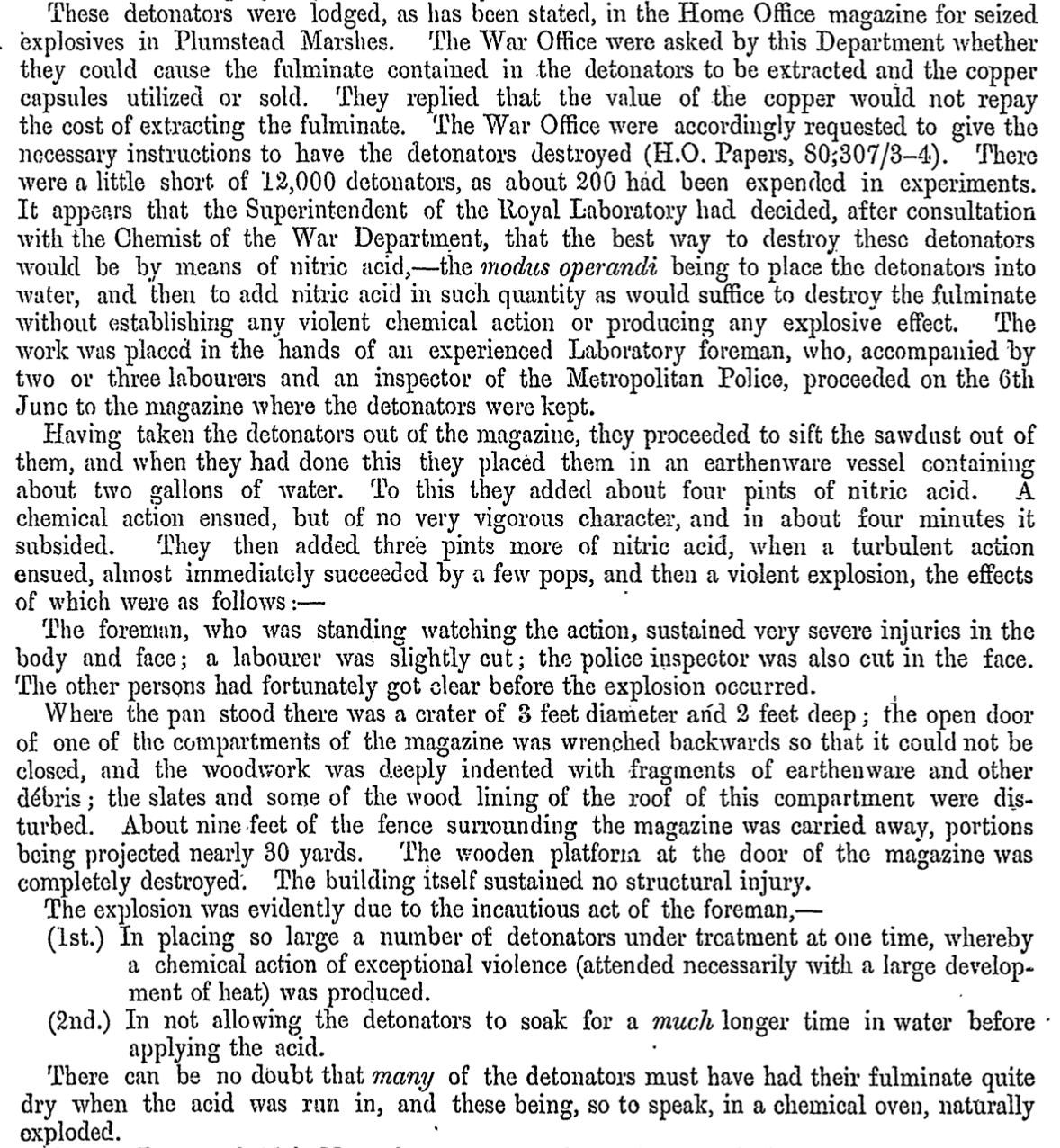

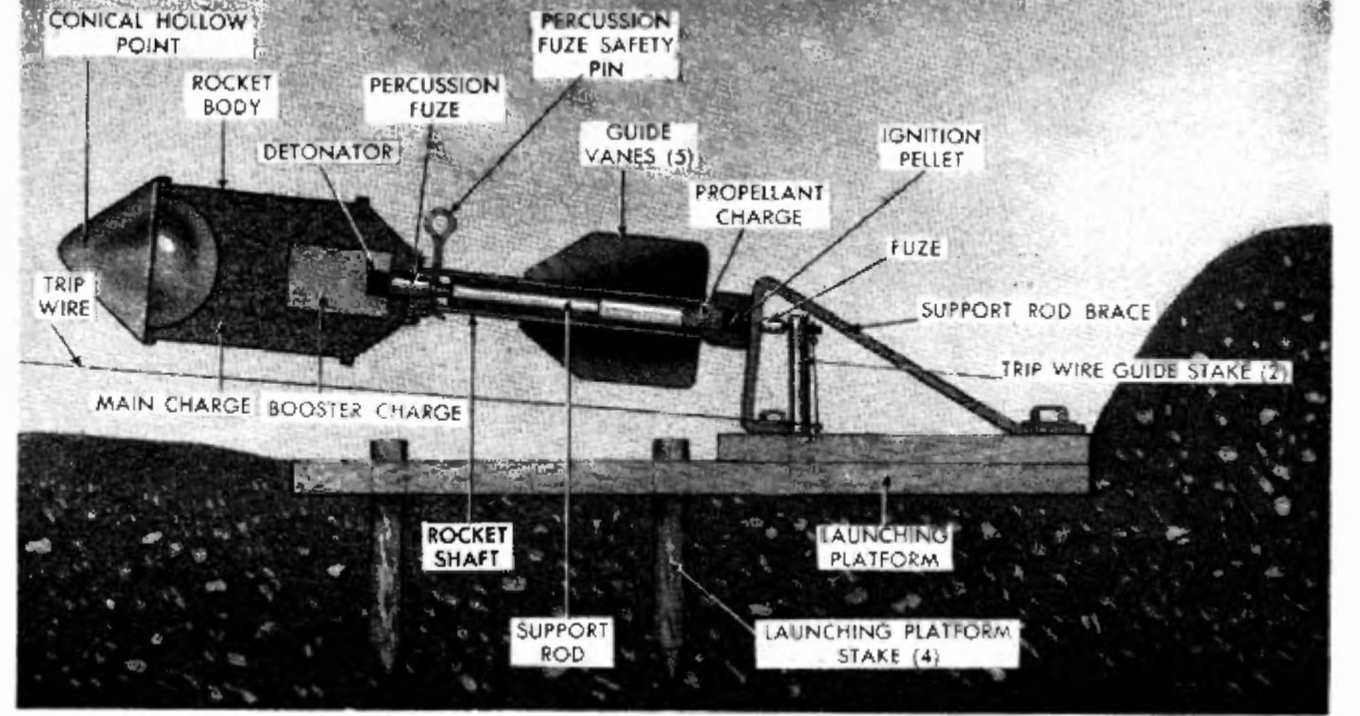

4. In WW2 Russian partisans developed a device that is remarkably similar. Not tube-launched but built for a similar purpose and with almost identical design principles. Here’s the pic from the 1950 report:

5. The Russians also concentrated significantly on additional circuits or mechanisms to booby trap charges. By introducing anti-handling and anti-lift charges, several of the devices used by the Soviets appear remarkably similar to what the British EOD community of the 1970’s refer to as “Castlerobin” devices. I’m not going to discuss this further here. But clearly there is a thought-process going on to prevent the render safe of devices, and target the EOD operator. The parallels in design are clear.

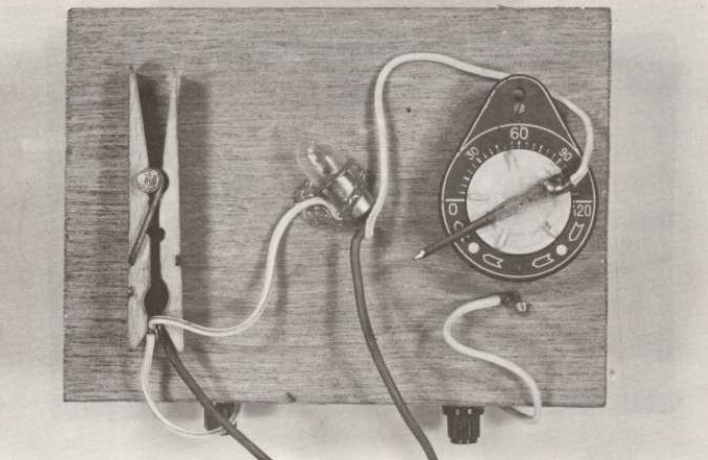

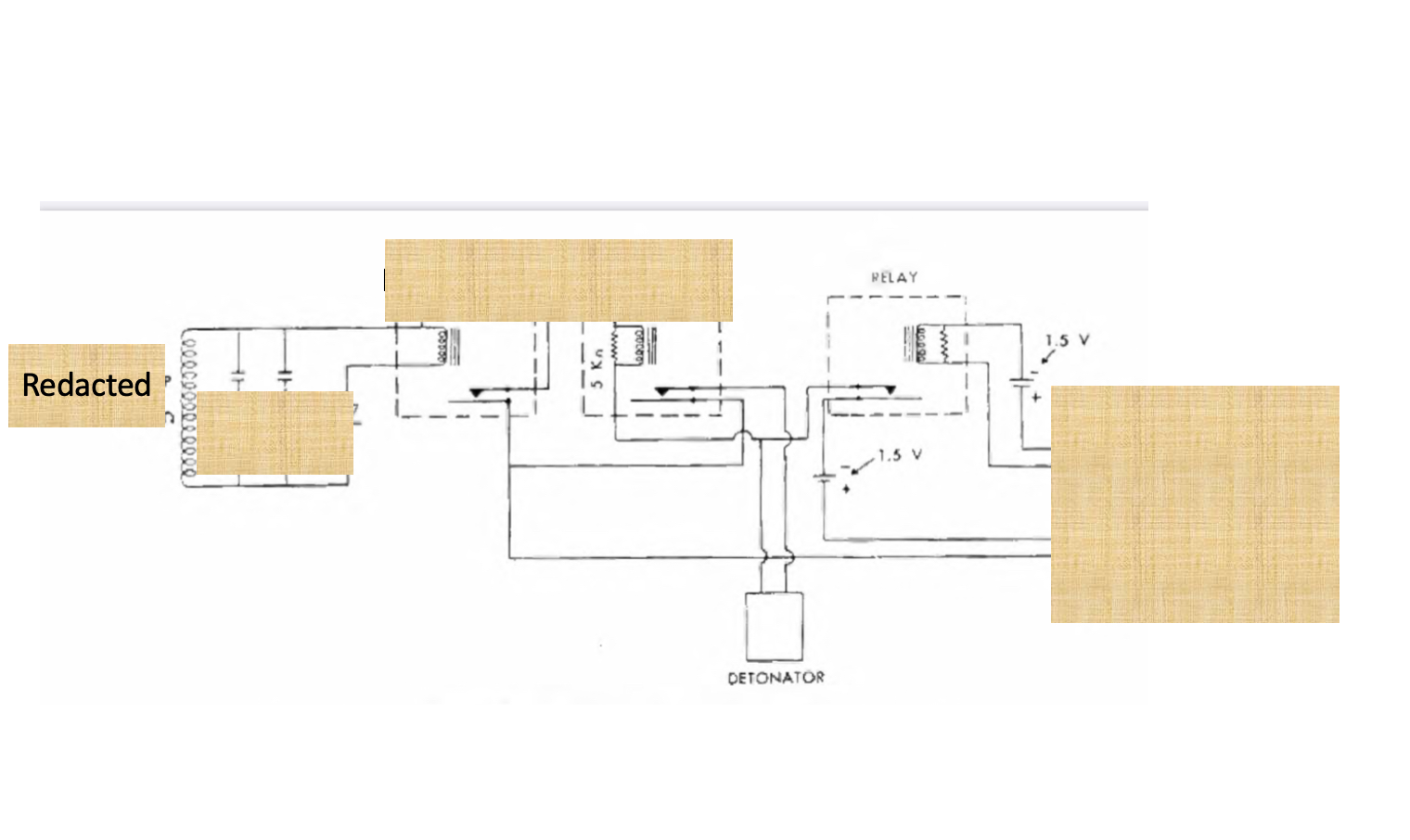

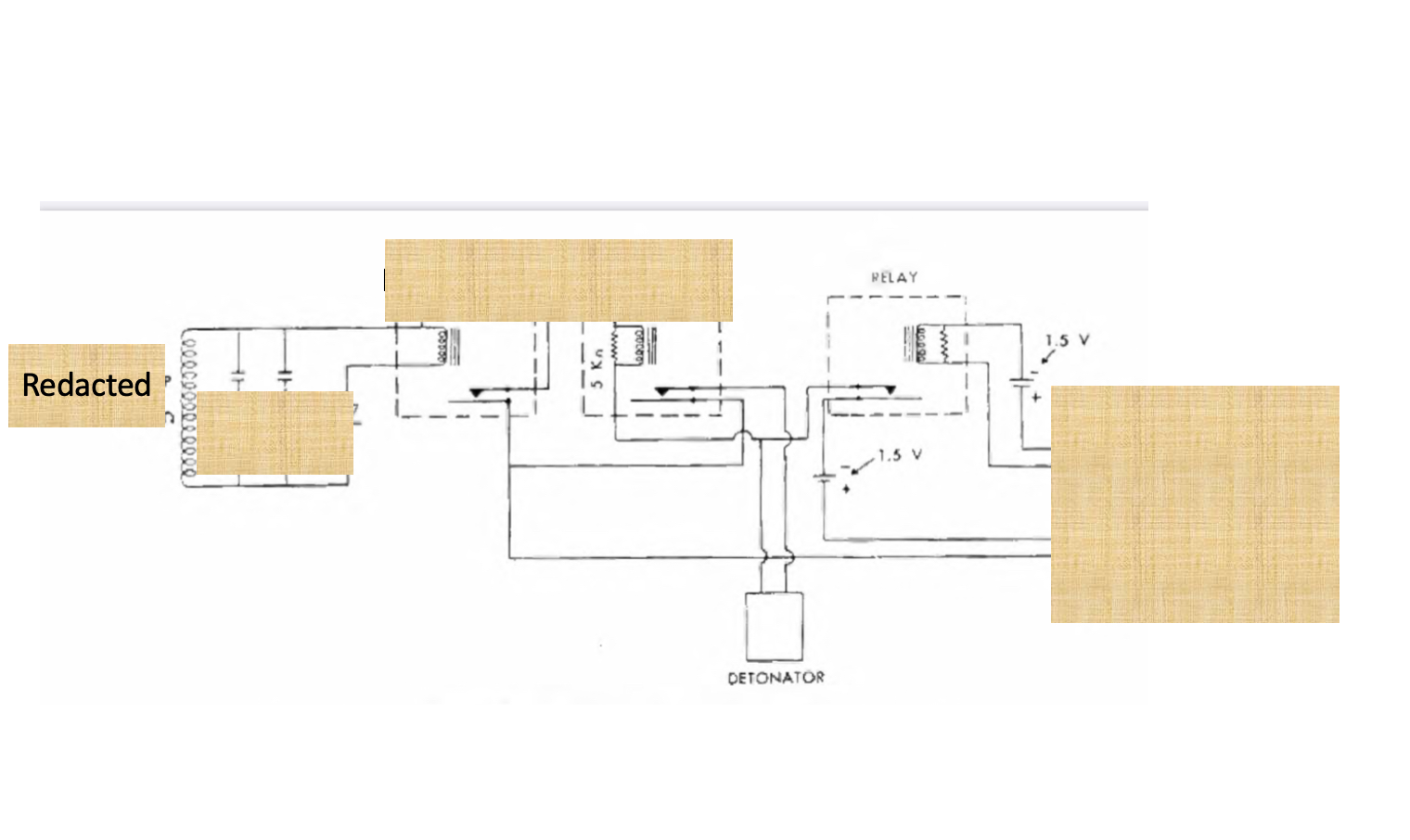

6. The creation of devices which target EOD activities went a step further with the introduction of a RF sensitive switch designed to initiate an explosive device when certain mine detection equipment was used. This was fielded in December 1943. Some of this equipment was captured by the Wehrmacht in January 1944, and rapidly exploited. 70 years later , technology which is triggered by the RF signature of certain EOD equipments would be regarded as a very high threat indeed – yet, here the Russians were in the early 1940s developing such technology. The device responded to a frequency of 800-2000Hz at short range, emitted by German EOD equipment. What is more, the Germans recognised the importance of such an advance, examined the Russian technology, identified some flaws, and developed their own version of the equipment. They also developed technical solutions to the threat. I find that remarkable, and some of you will share my surprise for reasons we won’t go into. Here’s an excerpt from the report showing the circuit to prove it is what I say it is – (I have obscured part of it for reasons explained earlier).

To be clear in my assessments: I’m not saying that the IRA devices of the late twentieth century were designed by the Russians – just that there are some odd parallels, that may be coincidences. Direct influence is possible but so, theoretically, is the potential for the IRA to have got hold of the American report written in the 1950s. It’s not secret. But we shouldn’t underestimate the fact that Starinov was training revolutionaries from around the world. I do think that these parallels once again highlight the importance of understanding the history of IEDs. The fact that Russian devices were so focused on countering EOD action is interesting and significant and deserves wider understanding. The general under-appreciation of the extensive, WW2 Russian sabotage campaigns using improvised explosive devices is barely recognised and deserves a much greater level of attention. Frankly it makes the efforts of the British SOE or American OSS look very paltry in comparison.

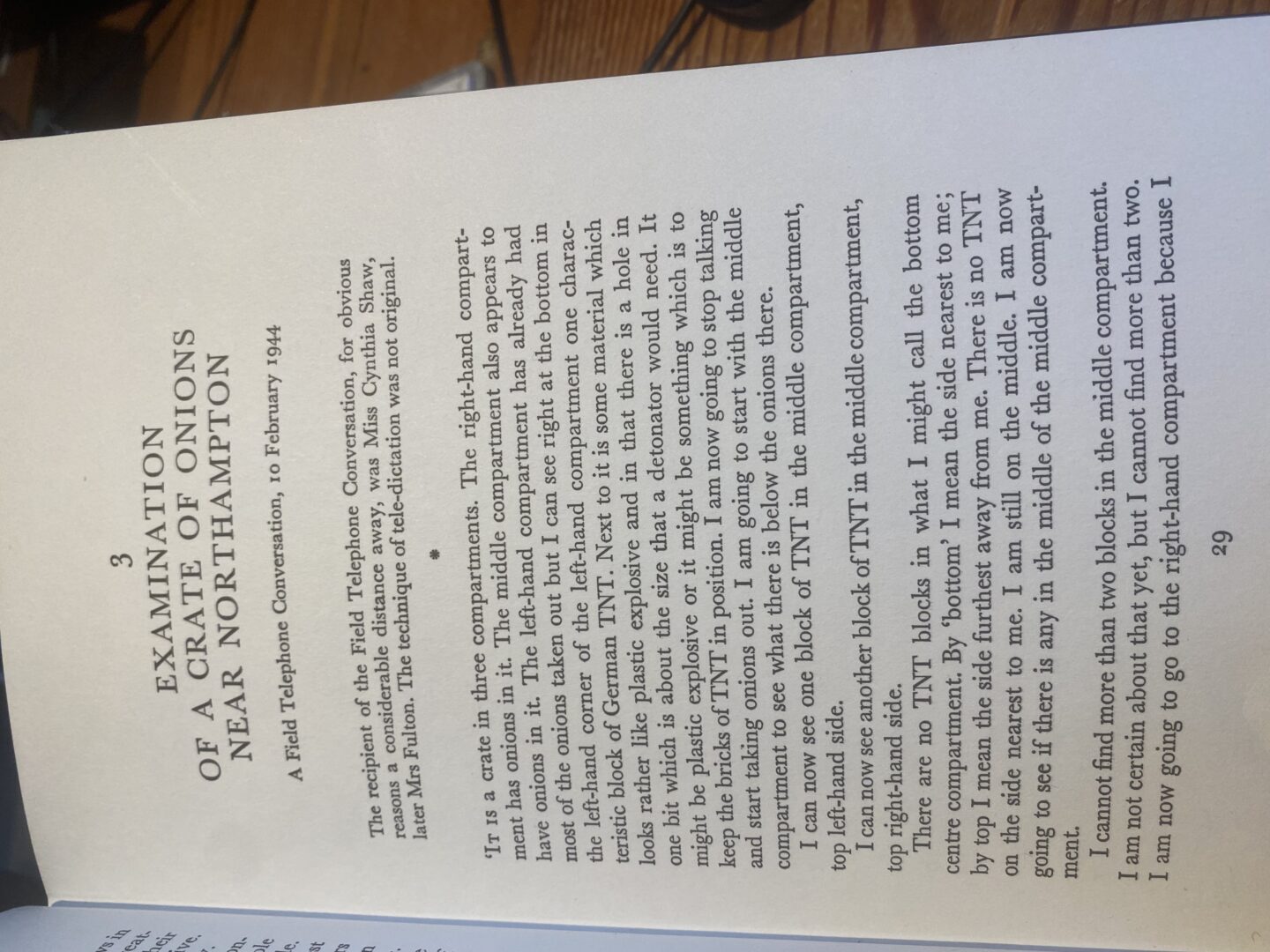

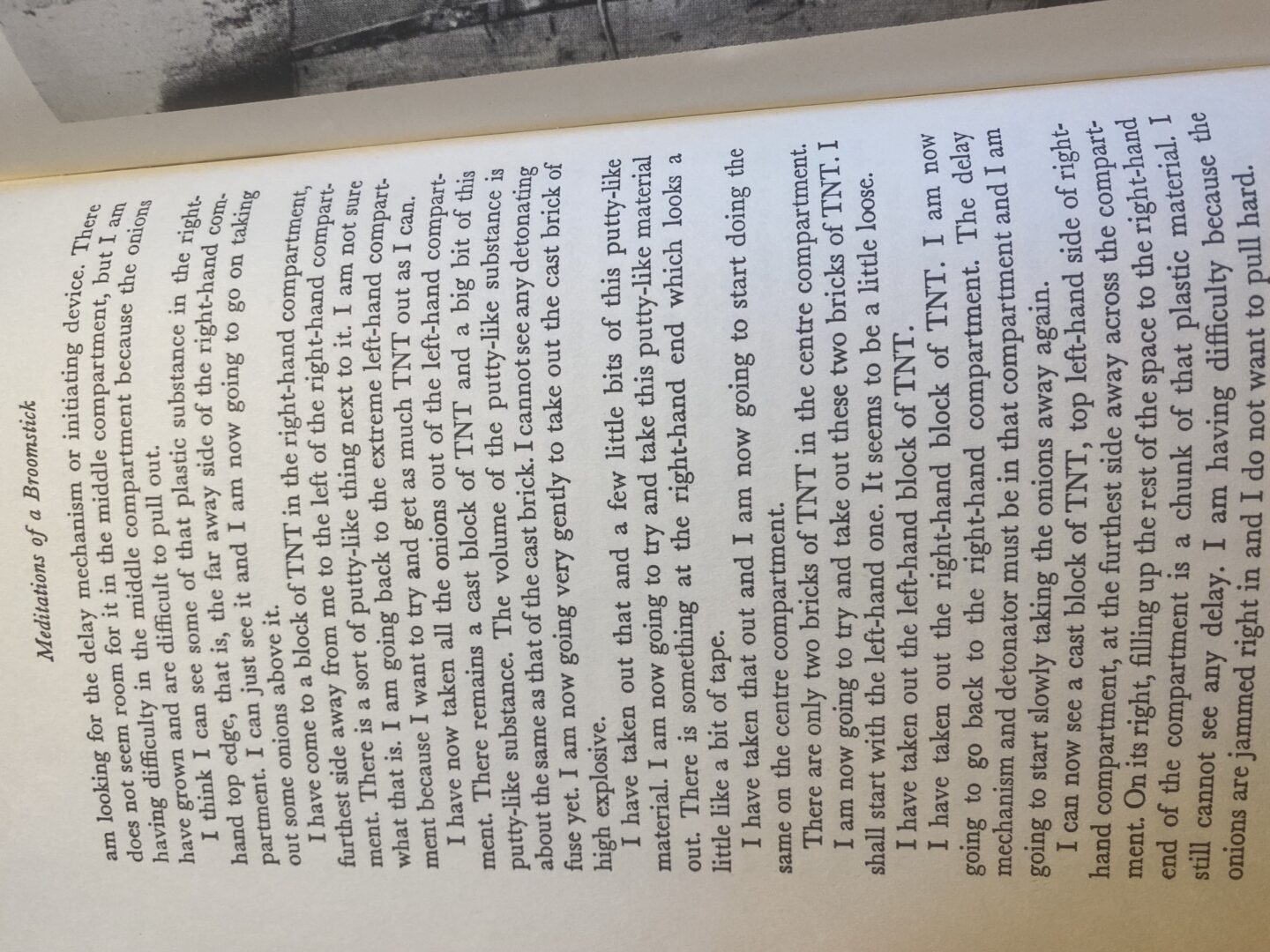

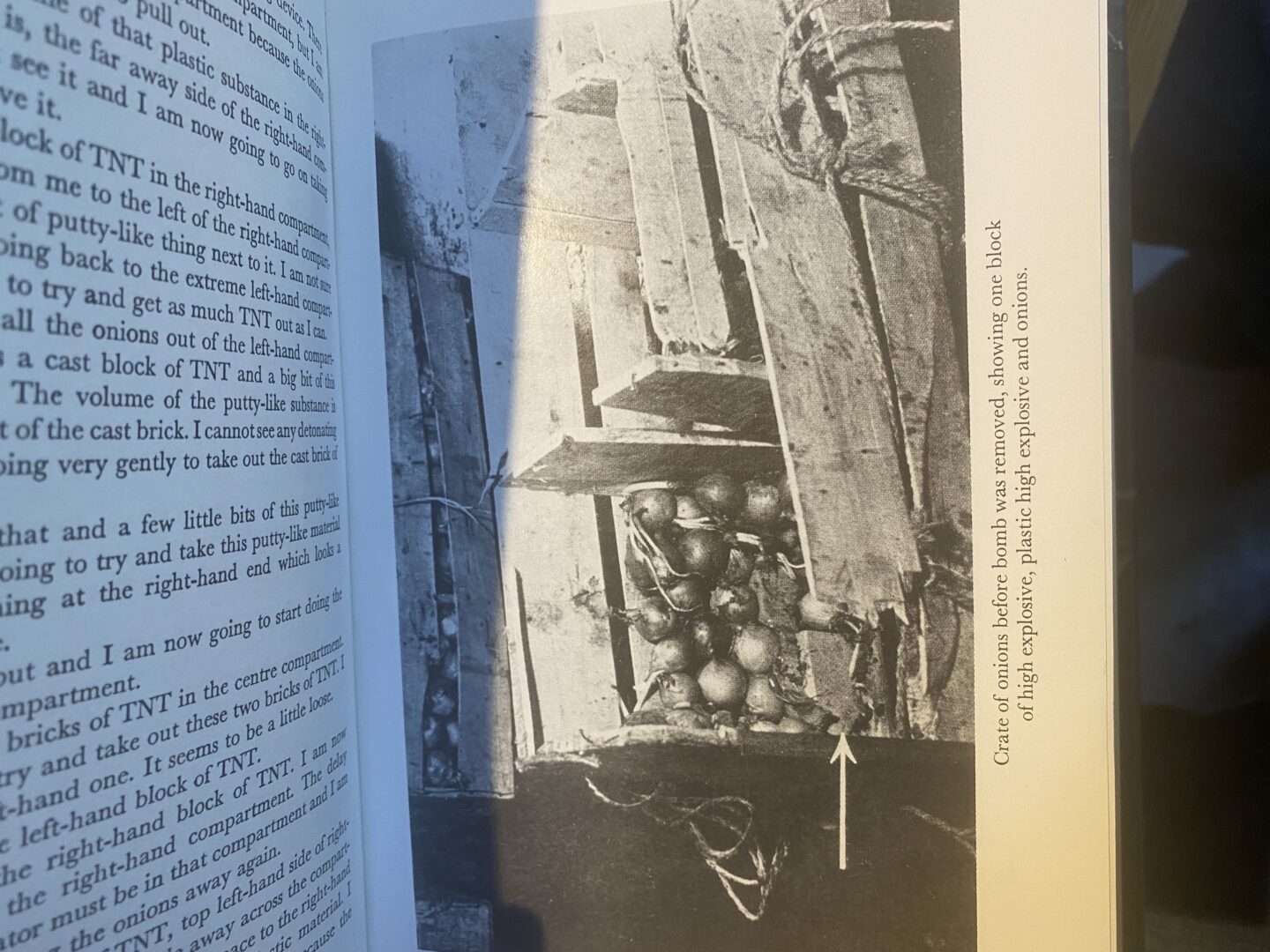

In future blogs related to all this I will address the following:

- Some Russian devices designed specifically for targeting railways – further to my series in the subject. Some were designed by Starinov himself.

- More technical details of the Russian F-10 radio controlled device.

- Some more details and photographs of Ilya Starinov, and an interesting story about the F-10 radio-controlled devices he deployed to assassinate German General General Braun in Kharkov in November 1941, and the role of a young commissar called Krushchev (yes, that one) in the operation, protecting Starinov from being arrested by Beria’s agents and “purged” before the device was detonated.

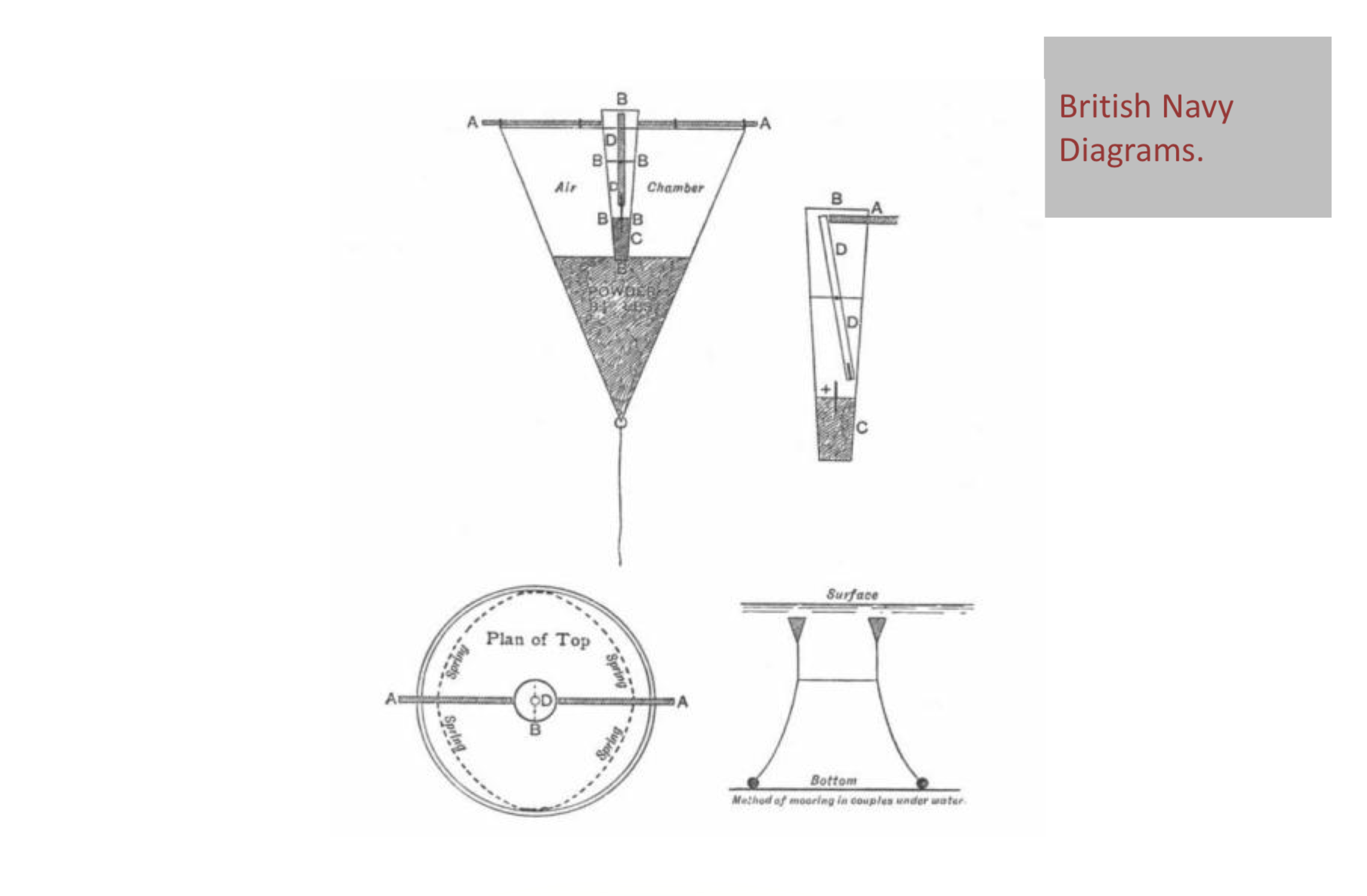

- An odd and fascinating series of parallels between this 1950s American report and another American report written in 1865 showing almost identical devices. History repeating itself again. Some of the Russian devices of WW2 are identical to Russian devices of the 1850s, and some other Russian devices of WW2 are very similar to American revolutionary devices of 1778.

All in all, this document is a bit of a treasure trove when put within the larger context of the history of IEDs over several centuries.