No comment.

No comment.

Interesting development reported here and elsewhere Basically a covert electronic surveillance device was discovered somehwere ‘interesting” in Iran which seemed to have had a Victim operated explosive penalty integral to it. Poses interesting theoretical challenges for security staff and potential EOD response needed to a find of a suspected surveillance device.

Reportedly similar devices were discovered over the past couple of years in Lebanon, monitoring phone lines, and an associated explosive incident occurred, but it’s not entirely clear if the explosion in that case was directly integral to the surveillance device or dropped from the sky.

Of course there is a common likely perpertrator in both the Lebanese and Iranian incidents, but the potential threat of an explosive device to reduce the evidence associated with the electronic eavesdropping remains whoever the perpertrator is.

I think there are also some intreresting deeper aspects to this, namely:

a. Is the purpose to deter searchers?

b. Or to destroy sensitive components? – if so what’s so sensitive that it needs destroying?

c. How would your design a surveillance device with an associated explosive payload so that it was certain to destroy the component you are concerned about.

d. What are the EOD implications of such a design.

Seperately, the fascinating accusations that Siemens components sold to Iran had small quantities of explosives (and presumably an initiation system) hidden within them is intruiging. Siemens deny even selling the components. But let’s guess that someone in the West provided a component with hidden micro devices in them for sabotage…. and that’s a fascinating concept.

Interesting article here about the psychology of “near misses”. It’s human nature to think that a project is a great success even if total disaster was missed by a fraction.

I think there’s an interesting corollary here for EOD operations. Most countries have an investigation system for examining when there’s an incident that kills or injures an EOD operator or bomb disposal technician. But if the operator is “lucky” and escapes unscathed there’s often no such investigation… and as the article points out, the individuals involved tend to repeat their potentially disastrous behaviour. To quote from the link “People don’t learn from a near miss, they just say “it worked, lets do it again.”” Ok ,there are the occasional exceptions, but on a global basis I think the statement there is no investigation of near misses is true as generalisation.

I’m fascinated that the FAA has addressed their problems in the area of “near misses” by analyzing the issues and pre-emptively fixing them so that there has been an 83% drop in fatalities over the past decade.

So… how do we collect and analyse the “near miss” data from EOD operations? (And you know that generally the answer is that we don’t). I think partly there is a culture in bomb techs globally to avoid such activity and partly there are frankly weak oversight structures over most EOD units. That’s provocative I know but I stand by what I’m saying – argue me back if you wish.

One of the facts quoted in the article is that a risk analysis firm suggests that there are between 50 and 100 “near misses’ for every serious accident. Instinctively I wouldn’t be surprised if that stat applies equally to EOD operations.

Most incident investigations of EOD casualties work backwards – I think it’s time the community turned this on its head and EOD organizations get used to trying to spot the near miss. I don’t doubt that would require a huge cultural shift, and collection and analysis of a lot of data but I think it’s needed.

There’s a nice bit of history available on the BBC iplayer here, a 1974 BBC documentary about the training and operations of EOD operators going to Northern Ireland. Apologies to those of you who can’t access iPlayer outside the UK.

The following comments spring to mind:

Update on Friday, June 15, 2012 at 2:31AM by Roger Davies

I forgot to comment about the SATO working hard to get his mug on camera. I assume much to the disgust of the very large team on the ground. I also couldn’t work out why he needed one radio to transmit and another to receive…. but then again SATO’s always know best don’t they…. : – ) And to me the berets looked just fine…

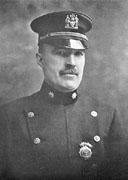

The article below on Inspector Eagan garnered quite a response so here’s another interesting character for the same city, within a similar line of work. This is Inspector Thomas J Tunney.

In 1905 the NYPD set up an organization to deal with the emerging threat of IEDs from the Italian “Black Hand” extortion gangs. This “Italian Squad” led by the famous New York Italian Cop Joe Petrosino played a significant and successful role in addressing the threat. In many ways they were an “IED task Force”. Tunney was assigned to this squad as a young police officer.

Petrosino was eventually assassinated while on a mission in Italy in 1909.

In August 1914 the NYPD Commissioner formed a “Bomb Squad” made up in part from the remnants of Petrosino’s Italian squad. Thomas J Tunney was assigned to command the Unit. To be clear this was not a bomb disposal unit at the time but, in essence, a detective division.

Tunney’s job initially was to continue the focus on Italian/mafia extortion gangs using IEDs, and the continuing anarchist revolutionary threat – and the emerging threat from German saboteurs. Tunney coordinated a significant effort from his team of 34 detectives, and led the use of double agents and detectives working under cover as well as extensive surveillance operations.. His team prevented an attack on St Patrick’s cathedral by some anarchists in 1915 when the bomb planters were arrested “in the act” by undercover police officers, one of whom pulled the fuse from the IED to prevent the explosion.

Tunney’s work expanded significantly in 1917 to counter the IED threat from German saboteurs. As the US entered the war Tunney was transferred directly into the Military Intelligence Service, along with 20 of his squad and indeed along with a number of senior NYPD officers. A significant proportion of the Military Intelligence Service (which before the war had consisted of three people) was then assigned in essence to Homeland protection duties to counter the German IED threat.

This military Unit, with Tunney as a Major had significant responsibilities for Investigations and security, combining some of the modern roles of Police, DHS and FBI in one unit. I think we can tell from Tunney’s stern demeanor that he was a competent man, and indeed the press reports of the time rate him very highly. Tunney toured the nation establishing special squads to deal with the German saboteur threat and the remaining threat from anarchists and other revolutionaries.

In 1919 he returned to the NYPD and wrote a book about his investigations, available on line here. However at this time he fell foul of NYPD politics (!) was demoted and assigned to the pickpocket crime division. His deputy, Barnitz, was also demoted, and assigned back to uniform. Tunney soon resigned and set up a private detective agency.

The following year saw a very significant VBIED attack on Wall Street, which as a crime was never solved. It is tempting to think that had Tunney been in charge he might have got to the bottom of it.

I have gathered some significant material on the German saboteur’s IEDs of 1915-1917 in New York and New Jersey (and elsewhere in the US) and will return to this subject in future blogs.