The EOD profession is one where lives are often at risk during operations. Many hundreds of lives have been lost over the decades on EOD operations of various kinds. Many more have been injured. There have been an uncountable number of “near misses”. But proportionally only a tiny few of these incidents ever get fed back to improve future EOD operations.

This article takes the position that the EOD profession’s cultural approach to risk has been, and still is, seriously flawed and much more can and should be done to develop what might be described as “open loop” reporting and “Black Box” thinking. I believe that EOD practitioners and C-IED operators in particular deserve better – and the hurdles that seem to be actively preventing such a cultural change need to be pushed out of the way. The status quo of accepting the current flawed and dysfunctional approach to adverse incidents whether they cause casualties or are simply “near misses” is morally unsustainable. Nobody wants to fail and we all want to succeed. But at a collective level, if we don’t admit and learn from mistakes, and create a culture where mistakes are recognised as opportunities to learn, then we will never move forward. The benefits of such thinking are not just in human lives. EOD Operations can become more efficient and effective by rational examination of mistakes. There is a need for a profound change. All too often the EOD profession at best only investigates casualties if caused on an EOD operation. Near misses generally get ignored and swept under a carpet. Too often even if investigations occur, they are frequently closed loop investigations with limited value, and blinkered, limited outputs.

Other professions too deal with risks to lives, and they have remarkably different responses – some of them outstanding and some dreadful. The EOD profession can learn from the good and recognise weaknesses in others that have strong similarities. In the last few years, technological developments are now able to provide systems to support a new approach and this article will touch on some of those.

Let’s look at two contrasting examples of how other professions deal with the issues of concern.

Aviation

Barely one hundred years ago, flying an aircraft was an incredibly risky activity. Technology was new, engineering of aircraft was still exploratory and safety systems were usually non-existent. In 1912, eight of fourteen US Army pilots died in crashes. Training schools had a 25% fatality rate. More recently, at the end of WW2, the first British jet fighter, the Meteor, suffered about 450 crashes. It was worrying but an accepted risk. Being a pilot of any aircraft was risky and dangerous. Any aircraft was a risky and dangerous thing to travel in. But in 2013 there were 36.4 million commercial flights worldwide, carrying 3 billion passengers worldwide. Only 210 of those passengers died, at an accident rate of one accident per 2.4 million flights. The reason for that is not just improved technology. What has also happened is an entire cultural change across a global industry. That is confirmed by the fact that members of the International Air Transport Association, which has more stringent procedures, have one accident every 8.3 million take offs, using pretty much the same technology as the rest of the industry. What is accepted in the aviation industry as a cultural norm is that errors and mistakes are reported and that errors and mistakes are an opportunity to learn and improve. In aviation two things have combined beautifully – technology and culture. In terms of technology, information to diagnose technical faults is much improved, quality systems have ensured components are correctly fitted, and communications and IT allow 24/7 monitoring of critical systems. Culturally there is a clear recognition that it is impossible for a pilot to learn every mistake personally – and that a global reporting system allows iterative improvement of training, drills, procedures and critical incident management so that success spirals up built on the mistakes of others. The industry accepts and understands that monitoring and recognising failure leads to lives being saved. A mistake or an error is seen as an opportunity to improve. Crucially the egos and the hierarchical sensitivities of pilots and crew are being recognised, and systems adapted accordingly.

Healthcare

Mathew Syed in his recent book “Black Box Thinking” compared the healthcare industry in terms of how errors and mistakes were addressed to the aviation industry. There are obvious differences in that only in rare cases are doctors and nurses lives put at risk. But with some notable exceptions, the healthcare industry is prone to mistakes and generally has a poor cultural attitude to such errors and mistakes. In 1999 the American Institute of Medicine reported that between 44,000 and 98,000 die every year as a result of preventable medical errors. A separate assessment concluded that over a million patients are injured every year during hospital treatment and that 120,000 patients a year die as a result of mistakes. A more recent study in 2014 suggests that figure may be much higher. That’s the equivalent of a lot of jumbo jets crashing. Errors occur in a variety of ways. Misdiagnosis, application of wrong treatment, poor communication, stress and overwork are common factors. What is becoming apparent however is that mistakes have patterns. Certain sets of circumstances lead to increased likelihood of mistakes. A medical error has a path or a trajectory, that if the system was able to highlight could warn medical practitioners that they were entering dangerous territory. Healthcare has another “built-in” problem, and that’s the medical hierarchy of senior doctors, junior doctors, nurses and support staff. It’s not suggested that this hierarchy needs doing away with but all to often medical mistakes are happening because of a poor flow of communication upwards or downwards of the clinical management chain. Importantly this hierarchy seems to lead to ineffective investigations, if they happen at all. In healthcare competence is equated to clinical perfection. A recent European study established that 70% of doctors recognised that they should report errors, but only 32% said they actually did so, and in reality, even that number has to be exaggerated. In healthcare around the world the culture has been one of blame and hierarchy. I wonder how many EOD operators would willingly report an error they had made?

Now, I would posit that currently the EOD profession has much more in common with current healthcare than current aviation. In EOD operations accidents happen for a variety of reasons. Amongst them are misdiagnosis, application of the wrong treatment, poor communication, stress, and overwork. There are other similarities that can be drawn between EOD and healthcare with regard to investigation or inquiries. But in EOD we can also blame a proactive enemy. Most EOD units are military or police based, with the concomitant disciplinary ethos. This leads to adversarial investigations when things go wrong and is one of the crucial hurdles to overcome and where attitudes and culture need to change. Investigations are strange things and I’ve participated in a number. Most investigations tend to stop when they find the individual or group closest to the accident who could have made a different decision, apportion the blame there and then close the investigation. There is rarely an understanding that mistakes are made due to much more complex contexts or series of events, and little effort is made to define that pathway of context in such a way that it can be characterised and used in the future as a “flag”, warning when circumstances begin to lead down the wrong path. A key issue is the fact that there is confusion and too often a dysfunctional link between an investigation to find the cause of an accident and the disciplinary requirement to apportion blame to an individual. This is the nub of the issue and the EOD community will always belong to strictly hierarchical organisations which are naturally inclined to require the apportion of blame. Somehow we have to change that attitude and recognise that there is a greater good than the need to blame individuals. In EOD, strangely, competence is also equated with perfection, and that’s simply unrealistic. That attitude is not even applied with rigour – with perfection being defined as “nobody got hurt this time”. As a community we have to address that attitude.

One particular technique that has been introduced in the aviation industry over the years, and is slowly being adopted in the healthcare profession is called “Crew Resource Management” or CRM. CRM is the careful use of a number of strategies to improve dynamic dialogue within a small team during a crisis. To me, the small team of an EOD response team working at an incident is directly analogous to the aircrew on a flight deck, or a surgical team in an operating theatre. The stresses are the same, the hierarchy is similar and the need for an effective dialogue between the team members is crucial. CRM addresses situational awareness, self awareness, leadership, assertiveness, decision making, flexibility and adaptability within the team. If one studies the nature of crises in aircraft and in operating theatres and match these, where possible, with the situations seen at IED response situations, there are startling similarities.

In a crisis, perception narrows. This is a standard physiological response to high stress. It is seen on flight decks and in operating theatres where key members of the team (such as the pilot or lead surgeon) become engrossed with solving a particular problem, ignoring other factors, especially time. Awareness of other issues affecting the incident drops sometimes remarkably. I’ve seen it personally in the command posts of an IED response incidents. CRM can address this issue by teaching other team members to intervene effectively, forcing, appropriately a broader view on the team leader. It is not easy and it requires training and the use of a few key techniques. But I’m excited by the potential of CRM to have a significant impact on improving safety and indeed the broader efficiency of EOD operations.

Historically EOD procedures have evolved, of course, by some form of analysis of previous successes and failures. I’m not suggesting that the profession should throw the baby out with the bath water and start afresh. But these historical developments were rarely built on volumes of validated data. They were usually built by careful consideration of a mix of actual reports from first and second hand sources, from instinct, from conjecture, and without the hard data that perhaps we can utilise today. There is an opportunity to be seized today, that modern technology can facilitate for us. Many years ago, I was one of these people working out procedures for the EOD unit I had operated in and then commanded. I did my best, I learned from the experience of others, I thought. But looking back my abilities were lacking in terms of understanding the limitations of human psychology. And I also lacked primary data sources. At best I had the reports of the operators themselves, completed “after the operation”, when a narrative cognitive bias or fallacy had time to establish itself in the mind of the operator. Addressing such human cognitive biases is tricky, and frankly my own understanding of such things limited the value of my task. It worries me that it has taken me nearly 20 years since I commanded that Unit to learn enough lessons about human psychology to realise I did a sub-optimal job back in the day.

So, here are suggested four measures which if introduced could bring to the EOD profession a measure of the Black Box thinking from which much could be learned and lives saved:

1. CRM could be easily introduced as a training culture. I accept that finding any time for training is easier said than done, but it appears the benefits would be clear. CRM training methodologies are already refined and ready for easy adaptation into the EOD community. I don’t doubt that the hierarchy of rank and experience is an issue that will need careful handling in certain EOD units. Conversely I have seen a more collegiate response of “equals” in a bomb squad also deteriorate into a self justifying loop. CRM should address this too. Introducing CRM will vary in its challenges between the different cultures in different EOD environments. CRM can, I believe, also incorporate referral to outside entities for technical support and authorisation – again training here might better enable the operator to brief his commander and seek authority for an off-SOP approach – and technology too can assist this with video and images.

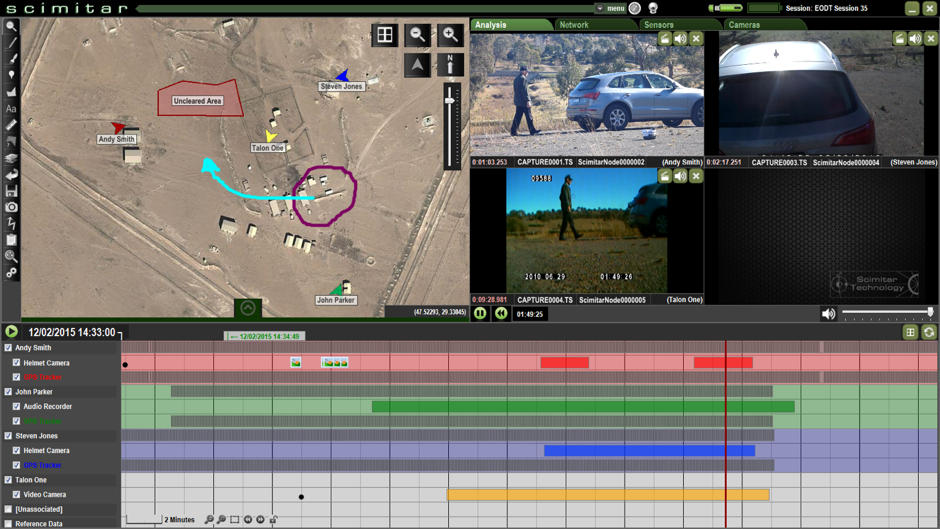

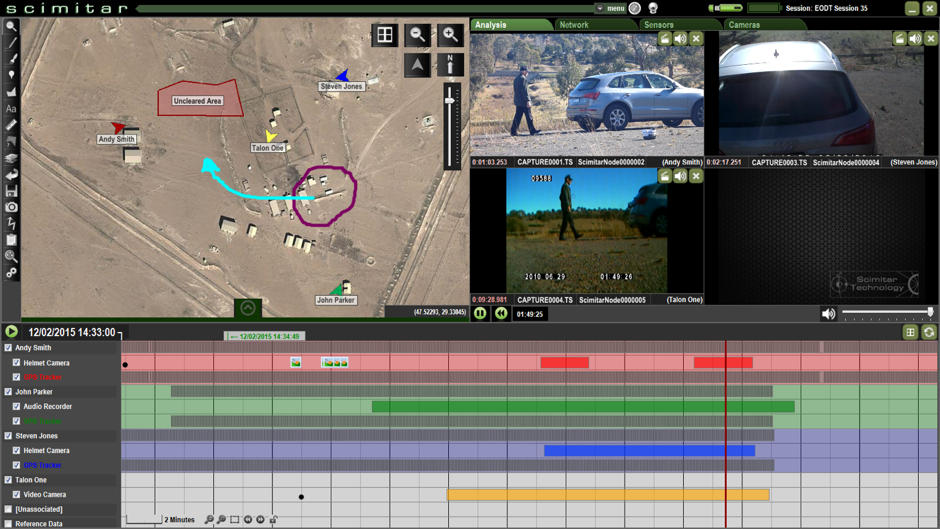

2. There are already technical solutions to the “Black Box” concept on the market. The “Scimitar” system is a good example, the principle of “the internet of things” makes it inevitable that all component systems of an EOD operation, including communications, CREW/ECM, video, audio, GPS, tools and indeed operator physiology will be fitted with sensors reporting (securely) to a data repository for subsequent analysis. The Scimitar tool (see image) gathers a range of geo and sensory data from individuals, and equipment within an EOD operation, as well as communications logs and videos.

So the operator and No2 are geo located with a personal tag, as is the ROV, along with its video stream. The data is presented in a variety of ways. The image shows a map overlay showing assets deployed to an EOD operation with various thumbnails presented of different video images. Along the horizontal is a timeline showing sensor captured events. This is, in effect, a black box for a bomb squad. It can be used as a post event tool, or even as a live briefing tool. Clearly, establishing such data collection in an EOD team must not be a logistic drag, and the intensity of certain EOD engagements on military operations in recent years has been remarkable – but all the more need to capture data automatically in these scenarios. Analytical tools will be able to spot error signatures and feed that back into debriefings, training and corrective procedural measures. Investigations will pin-point those errors which can be eliminated giving the operator and other operators value from the mistakes that he made. This can be done with relative ease with technology such as this. There are benefits too for the manufacturers who facilitate or provide this – they too can improve their products by careful analysis of the data. Aviation has a system which modern technology now allows to be a data-rich arena of information. Aviation safety has recognised this and optimised it, and continues to develop this concept. Now is the time for the EOD community to recognise that with some modern technology, an EOD operation can become a data rich environment, full of useful data and consequently lessons to be learned. I fully expect such lessons to assist a broader improvement in operational efficiency rather than just concentrating on safety issues. I suspect that the “Return on Investment” will be surprisingly good.

So the operator and No2 are geo located with a personal tag, as is the ROV, along with its video stream. The data is presented in a variety of ways. The image shows a map overlay showing assets deployed to an EOD operation with various thumbnails presented of different video images. Along the horizontal is a timeline showing sensor captured events. This is, in effect, a black box for a bomb squad. It can be used as a post event tool, or even as a live briefing tool. Clearly, establishing such data collection in an EOD team must not be a logistic drag, and the intensity of certain EOD engagements on military operations in recent years has been remarkable – but all the more need to capture data automatically in these scenarios. Analytical tools will be able to spot error signatures and feed that back into debriefings, training and corrective procedural measures. Investigations will pin-point those errors which can be eliminated giving the operator and other operators value from the mistakes that he made. This can be done with relative ease with technology such as this. There are benefits too for the manufacturers who facilitate or provide this – they too can improve their products by careful analysis of the data. Aviation has a system which modern technology now allows to be a data-rich arena of information. Aviation safety has recognised this and optimised it, and continues to develop this concept. Now is the time for the EOD community to recognise that with some modern technology, an EOD operation can become a data rich environment, full of useful data and consequently lessons to be learned. I fully expect such lessons to assist a broader improvement in operational efficiency rather than just concentrating on safety issues. I suspect that the “Return on Investment” will be surprisingly good.

3. Developing a common and radical post-incident investigation toolbox will of course be difficult to achieve, but I sense that very few EOD organisations have recently looked objectively at the the way they conduct such investigations. There is much to learn from other industries and developments in the psychological understanding of how individuals respond in stressful environments has much to offer. There is no reason why this revision should not be embraced by a number of national and international organisations and provided pro-bono globally. Thus, even if an issue cannot be shared internationally for reasons of security sensitivity at least a commonly accepted “best practice” of investigation will be applied that might be able to be of use. And the “best practice” should proactively identity where such information can and should be shared outside the unit and even internationally for the benefit of other bomb technicians.

4. The last of course, is the most difficult to achieve, that of changing cultures from the top to the bottom. There will be plenty who balk at them all citing hurdles such as security. But there have been some steps. The IED IMPACT program (www.IEDIMPACT.net) gives EOD warriors the opportunity to pass back their lessons learned in frank and candid ways. These wounded warriors, having suffered, really don’t want others to repeat their errors and their testimonies are powerful and moving. No-one thinks any the less of them for being involved in an incident. We think all the more of them because they are prepared to stand up and point out how things could have been done better. International organisations such as IABTI and the Institute of Explosives Engineers can pick up this thread and drive it forward internationally. Leadership is needed not just from these organisations but from within the current leadership of all EOD units and national authorities. This wont be easy – look how poor we are as an international community on sharing technical intelligence on IEDs – but we must strive to bypass these parochial hurdles.

Learn from the mistakes of others. You can’t live long enough to make them all yourself.

(This article was first published in “Counter-IED Report, Winter 2015/2016” and is reproduced here by kind permission of the Editor.)