In my research regarding the historical use of explosives, one of the avenues I’m digging away in is the use of explosives to break into safes. Clearly explosives have always been a potential tool for damaging locked doors, and containers. It’s intriguing to follow the development of safe design through the centuries, and see how the engineering technology followed the various threats posed. I also learned a few things along the way that I hadn’t realised like that fact that safes had two purposes, the first being to prevent the damage of documents and valuables by fire, and the second to prevent theft. In the former there’s an interesting thread of safe design that protected the contents by insulation, heat sinks and water vapour production.

In the mid 19th century, safe manufacturers became worried about the explosive technique of inserting blackpowder into the lock of a safe and initiating it there to blow out the lock, so various techniques to make “powder-proof” locks were invented, usually involving much more careful design which eliminated the space where gunpowder could sit in the lock. Thus the amount of explosive possible to insert in the lock was reduced. In 1914, an anti-explosive re-locking device was patented, in the usual tit-for-tat for battle that exists between explosive users and those defending against them.

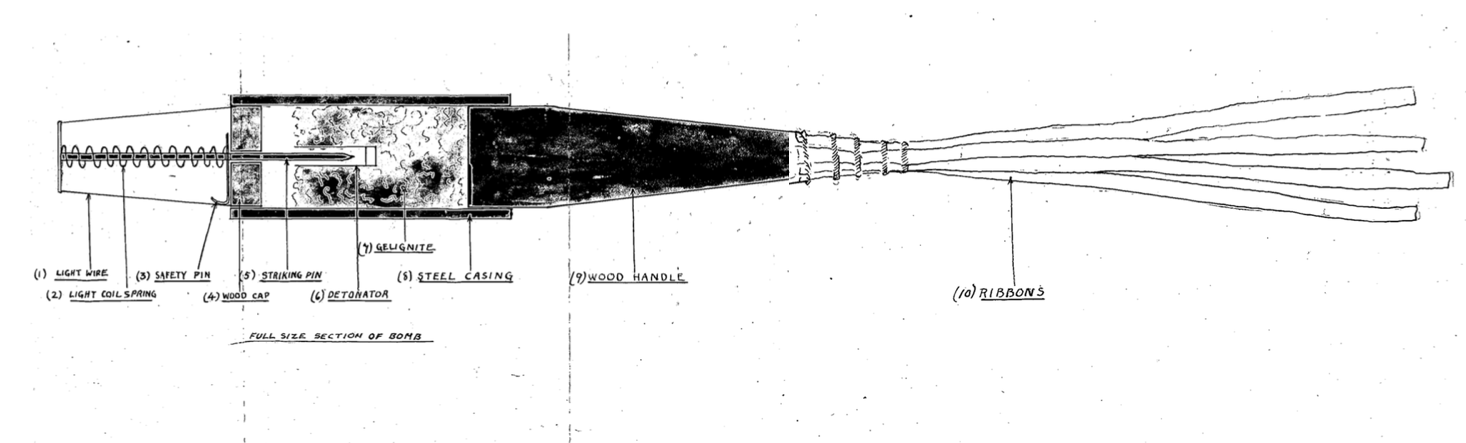

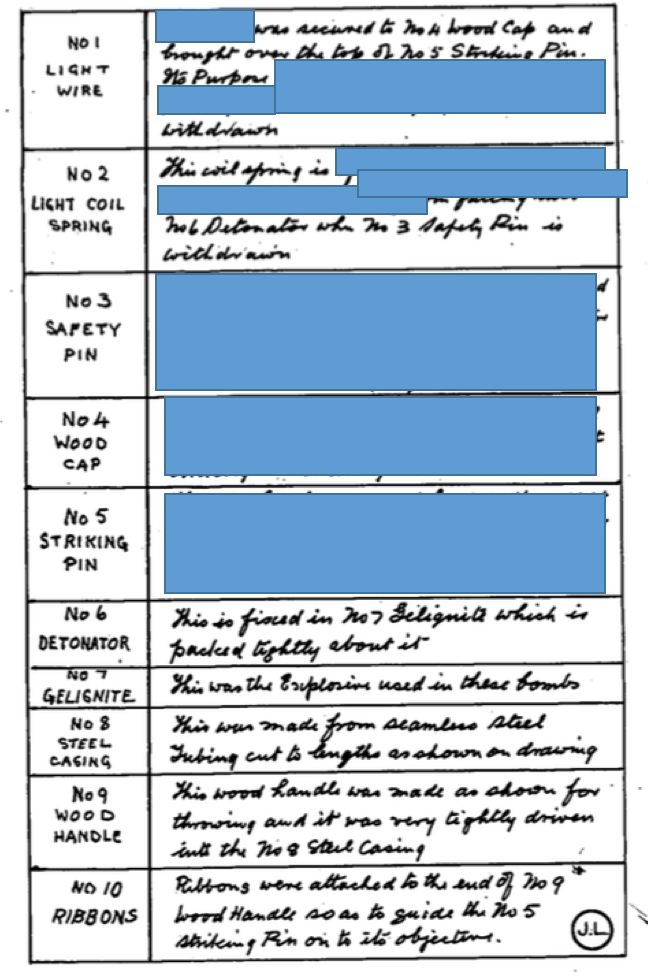

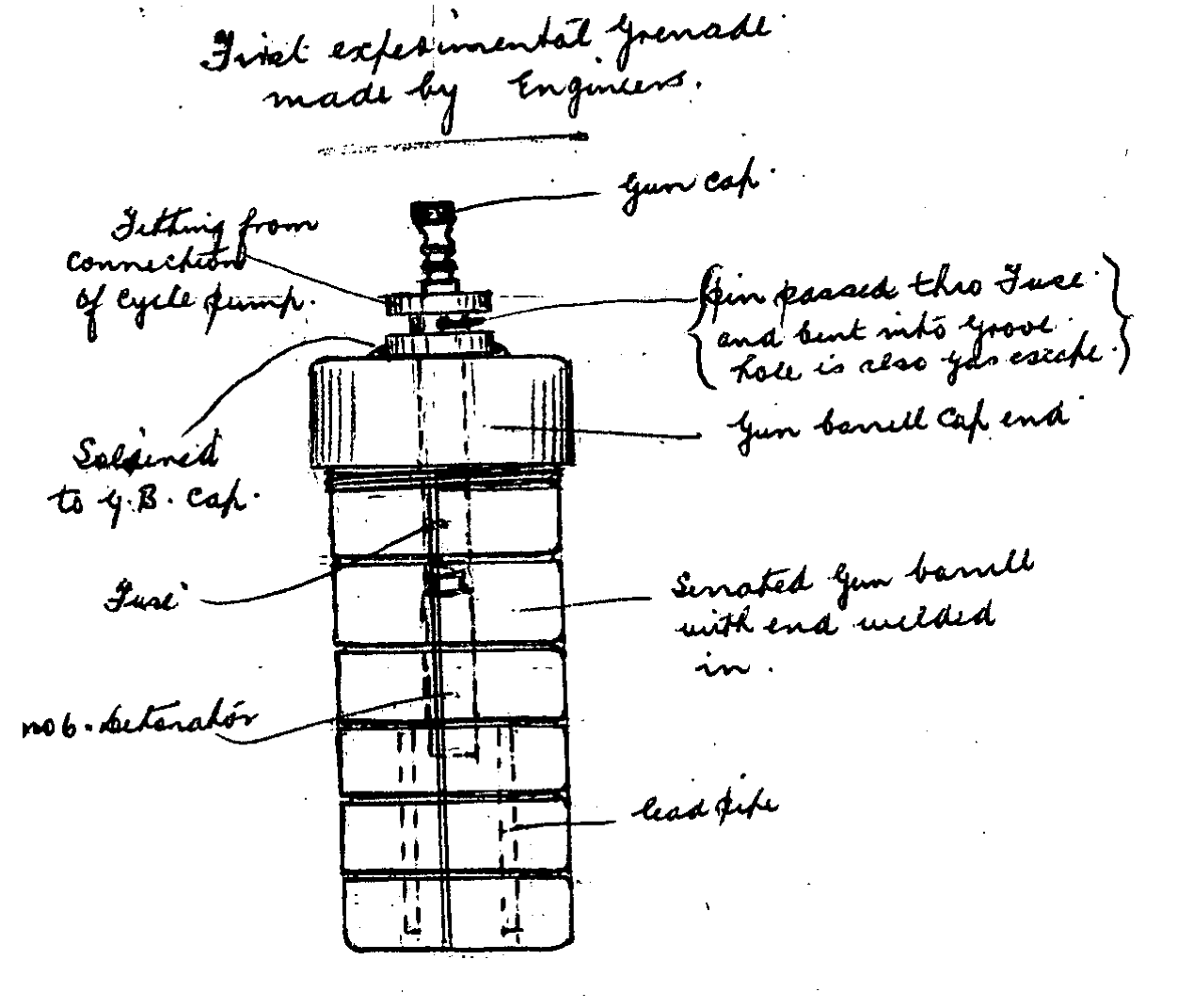

The hey-day of the explosive safe cracker was for about 20 years, from the late 1940s till about the mid sixties, allegedly because the wartime experience of a number of criminals had opened another box, Pandora’s, with regard to the clever use of explosives. A long time ago I was told that the establishment of the London Metropolitan Police Bomb Squad in the 1960s was at least partly because there were so much safe cracking going on and someone had to be there to pick up all the bits.

The slang term for an explosive safe cracker in the criminal community at this time was a “peterman”. The reason for this is a little obscure. Here’s a few suggestions:

- It’s Cockney rhyming slang. A safe is called “a can”, which leads you in the obscure logic of East End language to be “peter pan” which is shortened to “Peter”. So a Peter man was a man who dealt with safes.

- Many Scottish safe crackers ended up in Peterhead prison…. hence “Peter man”

- An ancient term for an explosive charge used to blow off doors was a “petard”, and this got transformed from Petard man to Peterman.

For further background there’s a nice website on the subject of Petermen, here , and a related site here.

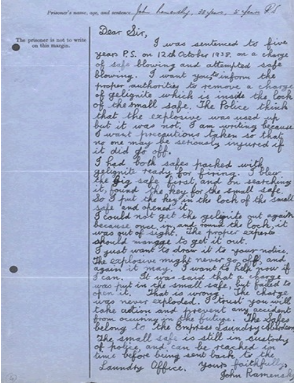

The Peterman site also details some famous safe crackers, including “Gentleman John Ramsay”. I quite like the fact that Ramsay, after one conviction wrote a letter to the authorities letting them know he’d left a quantity of explosives packed into another safe at the scene of the crime.

Beware though – many of the stories you can find about John Ramsay are probably not true. One story is intriguing though, and that’s that while serving with a specialist commando intelligence unit (30AU) in WW2 , he quietly repatriated Nazi gold and other treasures to Scotland, that he had recovered from safes in the German embassy in Rome. Wouldn’t that be a temptation to a career criminal?

Finally, here’s why you shouldn’t trust the electronic safe you find in your hotel room. When you can “bump” a safe (a widely known technique) who needs explosives? Google “bump opening safes” if you don’t believe me. There’s a lot of videos of similar examples. A lot of electronic safes aren’t safe at all.

Roger Davies

Roger Davies