As is often the case my previous post on the IED attack from the US Navy Submarine, USS Barb in 1945, sent me down an investigative alley. Here’s details a similar attack, this time launched from a British submarine, against an Ottoman train line in the Dardanelles in 1915 in WW1.

The leading character here is Lt Guy D’Oyly-Hughes, the first officer on the Royal Navy submarine, the E11. This submarine had an incredible aggressive series of operations against the Turks at the time of the Dardanelles campaign in 1915, sinking over 80 vessels on three operational tours. In August 1915, they hatched a plan to blow up a key railway line with explosives after attacks with its deck gun on the railway line at Ismid had proved ineffective. This was the railway line that ran between Istanbul and Baghdad, so was very much a key transport route.

Lt D’Oyly-Hughes constructed a small raft containing two barrels into which he packed the components for his device. The main charge was gun-cotton, (frequently used for such purposes in WW1 and earlier) initiated by burning fuze to a detonator. The burning fuze was itself initiated by a system we are not that familiar with these days – using a special “pistol” which fired a flash cartridge. The pistol was used by Navy and Engineer units because the system was much less likely to be damaged by water. Here’s a picture I have found of such a pistol, although this one may be from the late 1800s.

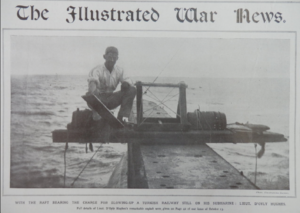

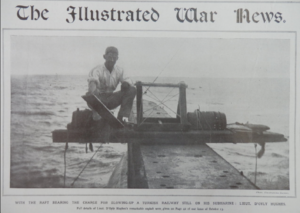

I have also, surprisingly, found two photographs of Lt D’Oyly-Hughes with his explosive raft, one on the transom of the submarine before the operation and the second as he entered the water off the coast of Turkey.

Before launch

In the water

The raft contained 16lbs of guncotton. Lt D’Oyly-Hughes, swimming, pushed the raft towards the shore. Here’s what happened next from the official history of British Naval operations:

Finding the cliffs were unscalable at the point where he landed, he had to relaunch the raft and swim further along the coast till he reached a less precipitous place. Armed with a revolver and a bayonet, and carrying an electric torch and a whistle for signalling purposes, he laboriously dragged his heavy charge up the cliffs, and in half an hour reached the railway. Finding it unwatched, he followed alongside the track towards the viaduct, but he had only gone about a quarter of a mile when he heard voices ahead, and soon was aware of three men sitting beside the line in loud conversation. It was impossible to proceed further undetected, and after watching them for some time, in hopes of seeing them move away, he decided to leave his heavy charge of gun-cotton where he was and make a detour inland to examine possibilities at the viaduct. Beyond stumbling into a farmyard and waking the noisy poultry, he managed to get sight of the viaduct without adventure, but only to find that he was beaten again. A number of men with a stationary engine at work were moving actively about, and the only course was to retrace his steps and to look for a vulnerable place up the line where he could explode his charge effectively. A suitable spot where the track was carried across a small hollow was soon found too soon, in fact, for it was no more than 150 yards from where the three men were still talking. But the place was too good to leave alone, and deciding to take the risk, he laid the charge, and then, muffling the fuse pistol as well he could, he fired it, and made off. For all his care the men heard the crack, started to their feet and gave chase. To return by the way he came was now impossible. His only chance was to run down the line as fast as he could. From time to time pistol shots were exchanged. They had no effect on either side, and after about a mile’s chase he had outdistanced his pursuers and was close to the shore. Plunging into the sea, he swam out, and as he did so the blast of the explosion was heard, and debris began to fall about him, to tell of the damage he had done.

Yet his adventure was far from over. The cove where the submarine was lying hidden was three-quarters of a mile to the eastward, and, when about 500 yards out he ventured to signal with a blast on his whistle, not a sound reached him. By this time day was breaking and his peril was great. Exhausted with his long swim in his clothes, he had to get back to shore for a rest. After hiding a while amongst the rocks he started swimming again towards the cove, till at last an answer came to his whistle. Even so the end was not yet. At the same moment rifle shots rang out from the cliffs. They were directed on the submarine, which was now going astern out of the cove. In the morning mist the weary swimmer did not recognise her. Seeing only her bow, gun, and conning tower she appeared like three small boats, and he hastily made for the beach to hide again amongst the rocks. Once ashore, however, he discovered his mistake, and hailing his deliverer, he once more took to the water. So after a short swim he was picked up in the last stage of exhaustion and his daring adventure came to a happy end…

Later in his career, Lt D’Oyly-Hughes rose in rank to command HMS Glorious, an aircraft carrier, but died when it was sunk by the Scharnhorst in WW2.

Interestingly I have also found a report of another, similar operation from a second British submarine, the E2 , a few weeks later in September 1915. First Lieutenant H.V. Lyon from HMS E2 swam ashore near Küçükçekmece (Thrace) to blow up a railway bridge. The bridge was destroyed but Lyon failed to return.

In WW2, the British Navy also employed this tactic in the Mediterranean. On 28 May 1941 Lt Dudley Schofield led a raiding party of 8, deployed from HMS Upright to attack an Italian railway line with pressure initiated explosives. I can find little description of the device other than it used “pressure pads”. A month later, on 24 June Lt Schofield, who had adapted his techniques from lessons learned, went ashore with one other and planted explosives on the Naples-Reggio di Calabria line. The charge failed to be initiated by a train so Schofield went ashore the following night to detonate the charge manually. Similar operations continued with Lt Wilson, (Royal Artillery) and Marine Hughes put ashore by HMS Urge in Sicily where they successfully planted a pressure initiated device on a railway bridge. There were quite a few other similar attacks from HMS Unique and HMS Utmost and other submarines. Some similar submarine sabotage operations took place in Norway.