I continue to be interested by the story of Herbert Garland detailed in this blog a couple of weeks ago. I have found some more details here (the primary source being Garland’s own reports held in the UK National Archives) of Garland’s adventures. Garland had a very dry sense of humour and his reports are full of droll phrases.

Some examples:

Garland went to the town of Yanbu in what is now Eastern Arabia to help the Arab revolutionaries defend it against the Turks. The defences were short of firepower, but Garland found an ancient Turkish cannon at the fort but as it “was apt to fire astern instead of forward we relied on its warlike appearance to help us scare off the Turks”

Here’s his own words describing the first IED attack on the railway at Toweira station, I think on the night of 20 February 1917. After a week’s camel ride to the attack point, Garland argued over the tactics for the IED attack with his Arab guide. The guide wanted him to place the device and then scarper, but garland wanted to watch the explosion from a nearby hill. As Garland says “The approach of the train five minutes after starting work settled the matter.”

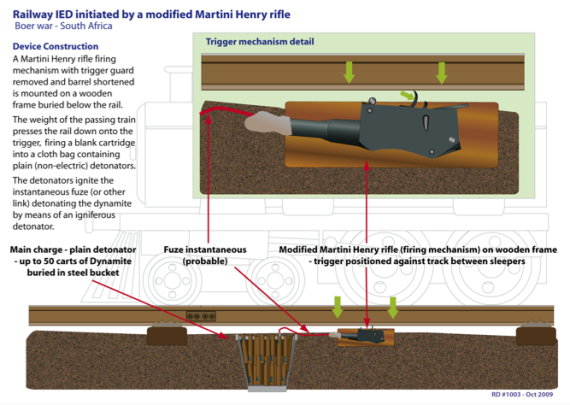

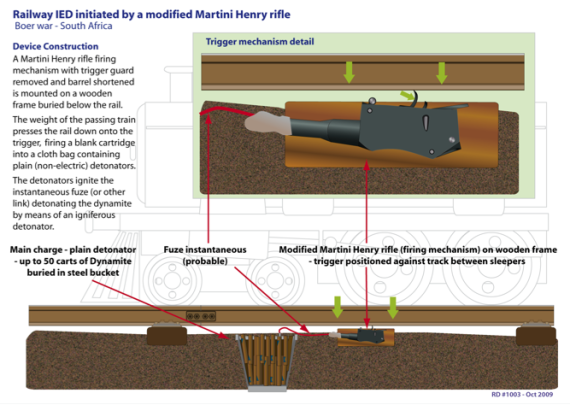

The trains rarely ran at night which was the cause for surprise. Garland, hearing the shriek of a whistle followed by the squeal of wheels was startled. He scrabbled for the three 5 pound cartons of dynamite which he jammed into the hole under the track he had started excavating. He pulled from under his black Arab cloak the action of the old Martini Henry rifle. Its barrel had been sawn off and the trigger guard removed so that all that was left was an oblong of brown steel from which the trigger protruded, exposed. This he loaded with a round of ammunition.. Turning the mechanism upside down, so the trigger was uppermost he wedged it under the rail, bullet pointing into the explosive, trigger brushing the rail above. The lights of the engine were now close, barely two hundred yards away, travelling at, he guessed, 25 mph. He got up and ran “ I wished I had devoted more time to physical training in my youth,” he says. His Arab robe swirled around his legs, as if determined to trip him up. Beneath his bare feet, the stony ground felt like ”carving knives, bayonets and tin tacks”.

As the locomotive’s front wheels passed over the device , nothing happened, but a split second later the heavier driving wheels of the train flexed the track enough to pull the trigger. The explosion threw the train from the track, followed by the carriages behind it as they fell down a stony embankment with a “clanking, whirling and rushing” noise. It was “the first time that the Turks have had a train wrecked” he reported. Some commentators have said it was the first ever act of sabotage committed by the British Army behind enemy lines. I’m not sure of that – its an interesting thought – if any reader of this blog can think of an earlier sabotage attack by the British, please let me know.

I’m truly fascinated that Garland was copying, in part, the IED design used by the Boers some 15 years earlier. I’ve blogged an image of that Boer device before – but here it is for ease. Somewhat different but very similar in many ways.

I’m intrigued as to how Garland learned about and decided to copy the Boer IED. The concept of using a bullet fired from a gun as an initiation mechanism was not that unusual – indeed some of the fenian devices of the 1880s used a similar principle.

In looking closely at the role of the Arab Bureau, of which Garland and Lawrence were part a couple of interesting things come out:

Firstly, while I admire Garland’s efforts immensely, of course I’m torn because essentially he was planting IEDs and I’m normally interested in defeating IEDs and view with contempt those who plant them so there is a dichotomy there that I’m struggling with.

If you were to think of modern day night vision images of local terrorists planting roadside IEDs being planted next to a road in Iraq or Afghanistan there is very little difference between that and the descriptive image Garland gives of himself scuttling away from the railway track near Toweira in 1917.

Separately I’m intrigued as to the parallels with the Arab Bureau and modern day “special forces operations” in terms of working within a country aiding revolution, identifying future leaders amongst a revolution, encouraging the right people, discouraging the “wrong” people, and enduring battle alongside indigenous forces. Garland and indeed Lawrence didn’t regard themselves “special forces” and were essentially amateur, but there is no doubt that the paradigm they developed by the seat of their pants is identical to certain SOF principles being developed (again) today.

Next I’m going to hunt out details of Garland’s grenade launcher.