There is much focus today on “augmented reality” technology and a fair proportion of this is in the defence world. Systems like the Google Glass project and a number of others can be used or adapted to add visible data and tactical information and analysis to a soldier, overlaying that data on what he is seeing. Very hi-tec. So I was surprised when during some research I came across the details of a genuine Augmented Reality technology being used for a defence fire control system in the 1860s over a 150 years ago.

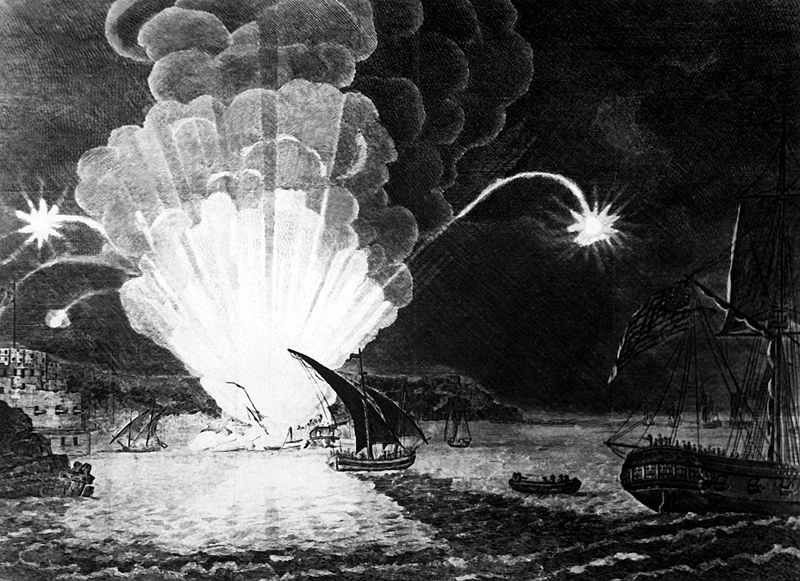

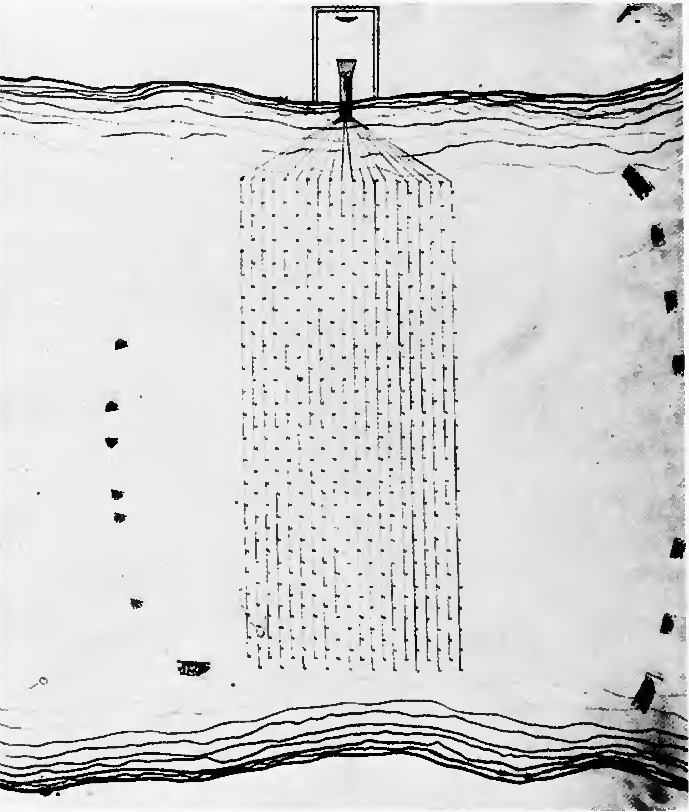

During the 1860’s a room-sized camera obscura was used to conduct military research in Belgium. The system was set up to project a “live view” of the River Scheldt in which an electrically initiated underwater mine had been placed. That view was projected onto a large table. The operator of the camera obscura marked the position of the submerged mine on the viewing table, in effect as a data overlay with the image. An enemy ship passing over the mine could therefore be seen and as it approached and when in the optimal position, the mine could be exploded by remote control. The experiment was repeated in Venice in 1866 by Austrian engineers who then held the city, with more elaborate steps to pinpoint the location of the mine, and in this case a series of mines. As a small boat laid each mine, the operator recorded that position and marked it on the image table. The boat then did a full circle, I’m guessing 20ft around each mine position, and the operator recorded that circle on the viewing table, in effect becoming a specific kill zone, for each individually activated mine, presumably numbered, overlaid on the live image. This ingenious arrangement was never tested in action.

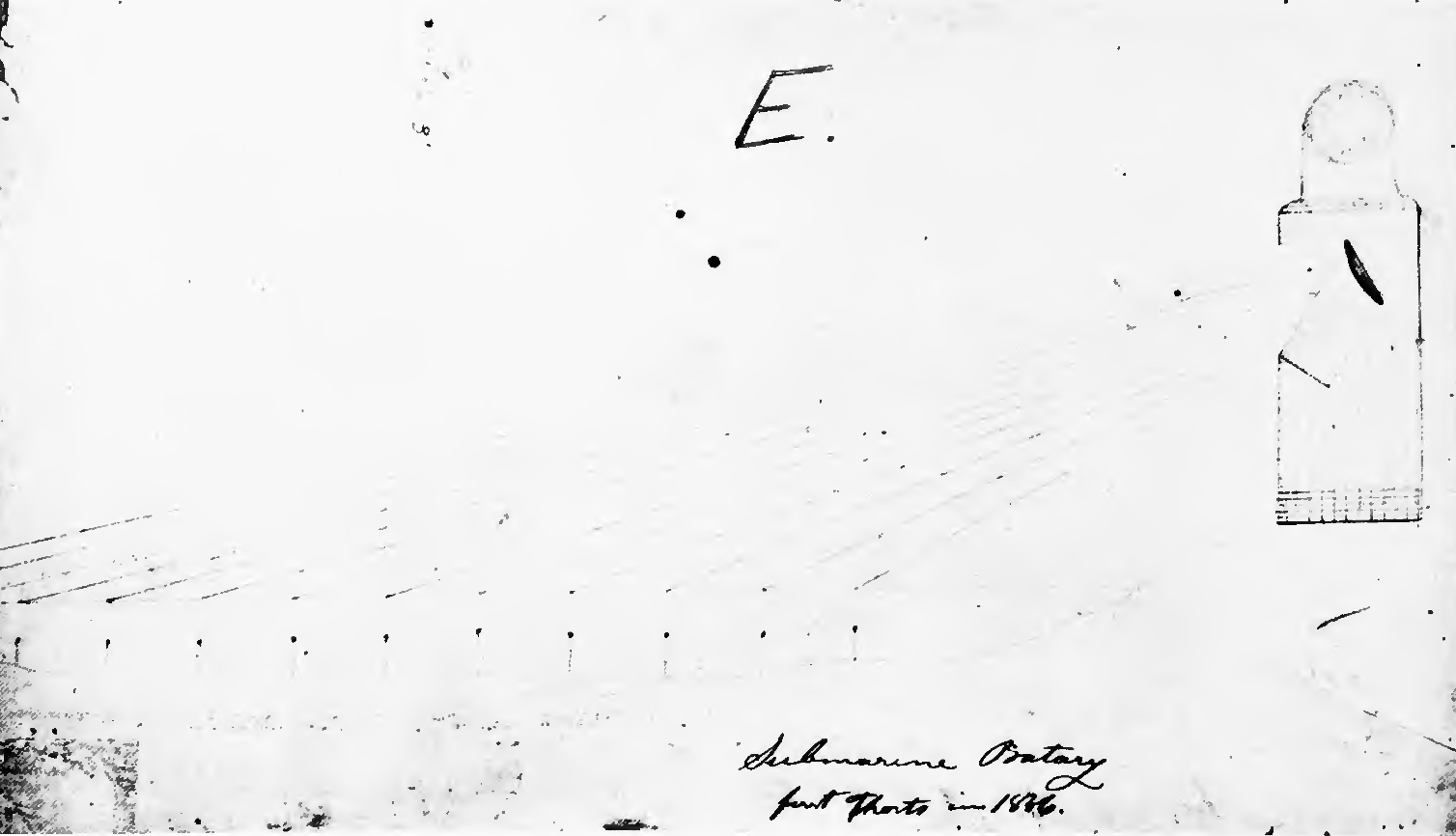

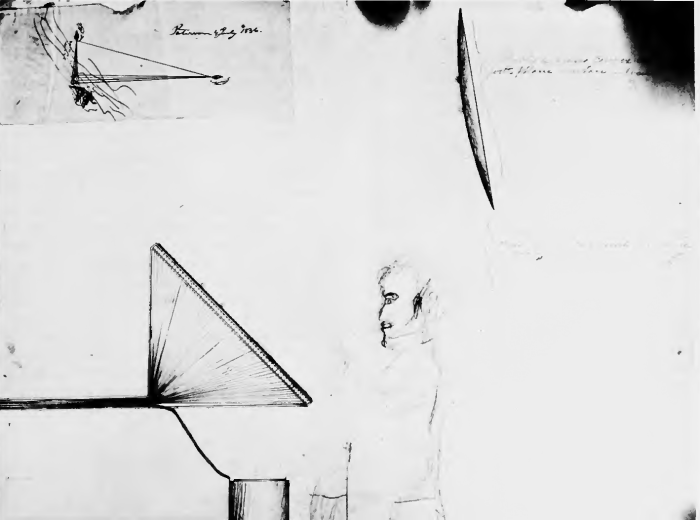

Doing some more digging on this subject I have found oblique references to the connection with Samuel Colt the American inventor. Colt did indeed develop systems for initiating observed river mines in the 1830s, and this poor diagram, dated 1836 labeled “Submarine Batary first thorts 1836”, drawn by Colt, seems to indicate a reflecting lens which might project an image onto some form of viewing screen. To me that looks like a version of a camera obscura.

This second diragam, an overhead diagram, might be interpreted as a viewing position with a lens in the building at the very top, which projected a view of the scene over a set of terminals for initiation.

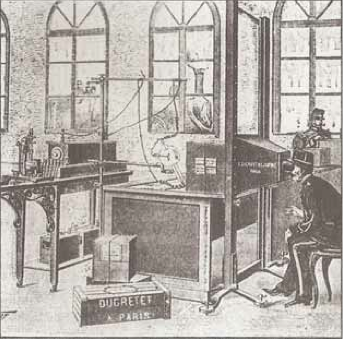

This third diagram, again by Colt begins to make sense, perhaps. Note the large lens in the upper right, I think reflecting the camera obscura image onto the actual reflective control panel. Thus the image is projected onto the switches. I think….

Colt was incredibly secretive about his inventions, but I think there is a very good possibility Colt had invented something similar to (and possibly more sophisticated than) the 1866 Austrian camera obscura system, but 30 years earlier, or at least had the concept in his head. Due to Colt’s obsessive secrecy I can’t be quite sure. It is possible that as well as protecting the commercial rights to the system with this secrecy, Colt was also very aware that the observation towers housing the “camera” had to be placed on prominent, well visible, high ground – making them potential targets for the dastardly British fleets which his systems were designed to combat. There were plenty of good reasons to keep the observation system secret. So it is intriguing to wonder how a system, somewhat similar ended up on the River Schelde some years later.

It would be interesting to replicate Colt’s augmented reality fire control system of 1836, wouldn’t it?

Roger Davies

Roger Davies