I’ve written before how command-wire electrically-initiated explosive devices have been around for a couple of hundred years now. But I want to look at the subject again, obliquely, by highlighting the different environments in which these devices have been used. There are one or two fascinating diversions in this post.

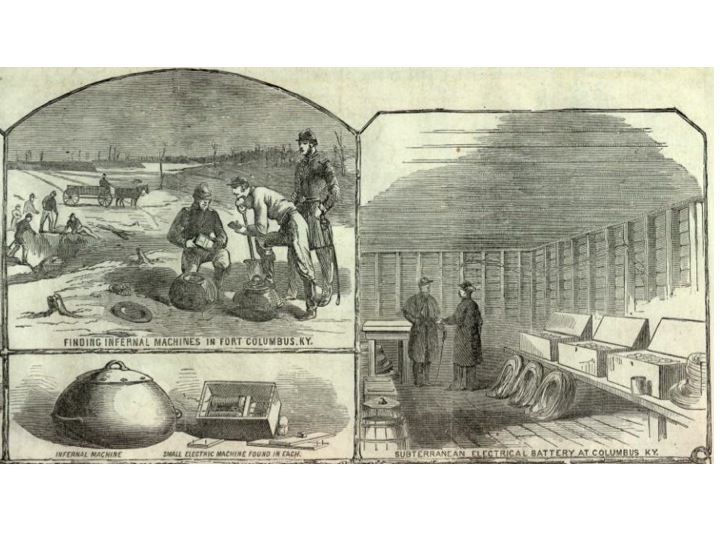

Clearly, command wire devices on “land” have been around for centuries, derived originally from the “string” or “cord” pulled devices of the late 1500s such as the one discussed in an earlier post here. Then in the early part of the late 1700s/early 1800s (started by Benjamin Franklin who was the first to electrically initiate an explosive (I think) they spread into broader use. See these earlier posts here and here. In the 19th century, “minefields” were sometimes not constructed from autonomous victim operated mines, but rather command initiated devices, controlled from some form of command post. See this one below from the US Civil War era, showing an underground store from which “torpedoes” (buried mines) were initiated on the battlefield in front.

Today electrically initiated command wire land based explosive devices are pretty common as terrorist ambush devices, with the only issue being the potential visibility of the wire or the process of laying the wire between device and firing point.

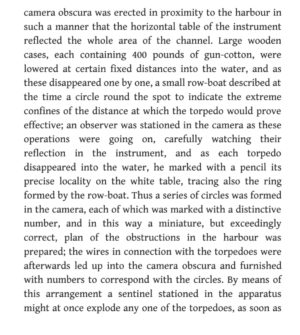

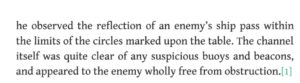

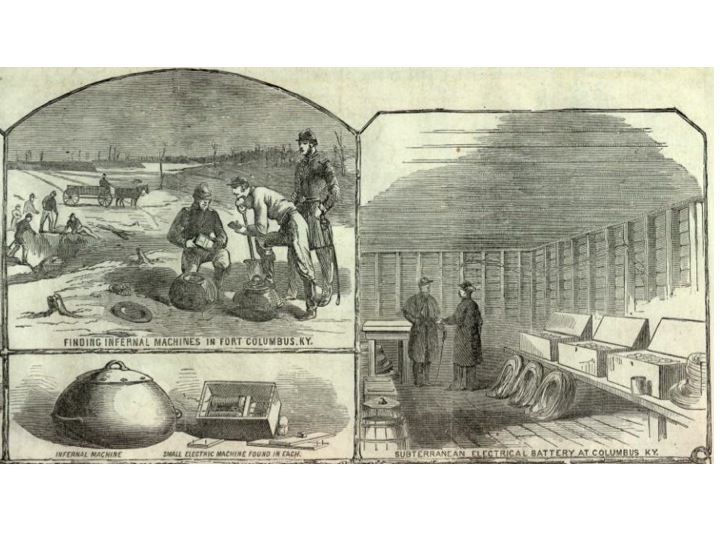

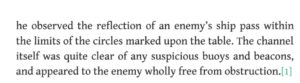

Various engineers and inventors in the early decades of the 1800s refined electrical initiation and waterproofed systems to allow them to be used for command initiated defensive minefields on coasts or in rivers – these include the German, Siemens, the Prussian Schilling, the Russian Schilder and Pasley, the British Royal Engineer used such waterproofed electrically initiated charges for demolition purposes. By far the most interesting use, however and one which strangely receives scant attention (perhaps not so strangely given the secrecy of the project was Samuel Colt’s 1836 concept of an “Underwater Battery”). This was an electrically initiated complex defensive array of underwater mines designed to protect ports and rivers. They key part of this invention however was not the electrical initiation but Colt’s remarkable command system which I’m 99% certain used a “camera obscura” to project a live image of the area in which underwater mines had been carefully placed. The image was projected onto a “command panel” with electrical contacts built in so that when a ship approached the position of the mine the image of the ship was projected onto one of many metal contacts on the “command panel” . All the operator had to do was to use an electrical cable from the battery stored underneath to the contact where the ship was displayed on the command panel when the live image of the ship covered it and that device would be initiated. Rather like a “magic wand” – touch the live image of the ship you wish to destroy and it will explode Such a remarkable integrated “augmented reality” observation and command system seems to be 200 years ahead of its time. I have written about the system before here. Someone needs to recreate one of these for a TV show.

Colt’s control panel. Note the convex mirror reflecting the image of the minefield from above.

Colt wrapped his invention in secrecy, but I think its pretty clear to me that his ingenious observation and control system was a first for initiating complex command wire minefields. Interestingly, a few years later it appears the Austrians used such a system to protect Venice around 1860. How they got hold of Colt’s idea, I have no idea. Here’s how it was described:

Here’s an image of the Austrian command post.

I remain fascinated by this system. A remote, visual, augmented-reality weapon system, invented by Samuel Colt in the 1830’s. Kept secret, then deployed by the Austrians in the 1860s then forgotten about. Wow! And only a few years ago people were shocked when terrorists in Iraq used a video camera overlooking an IED to know when to initiate a device, but Colt beat them to it by 170 years on the Potomac!

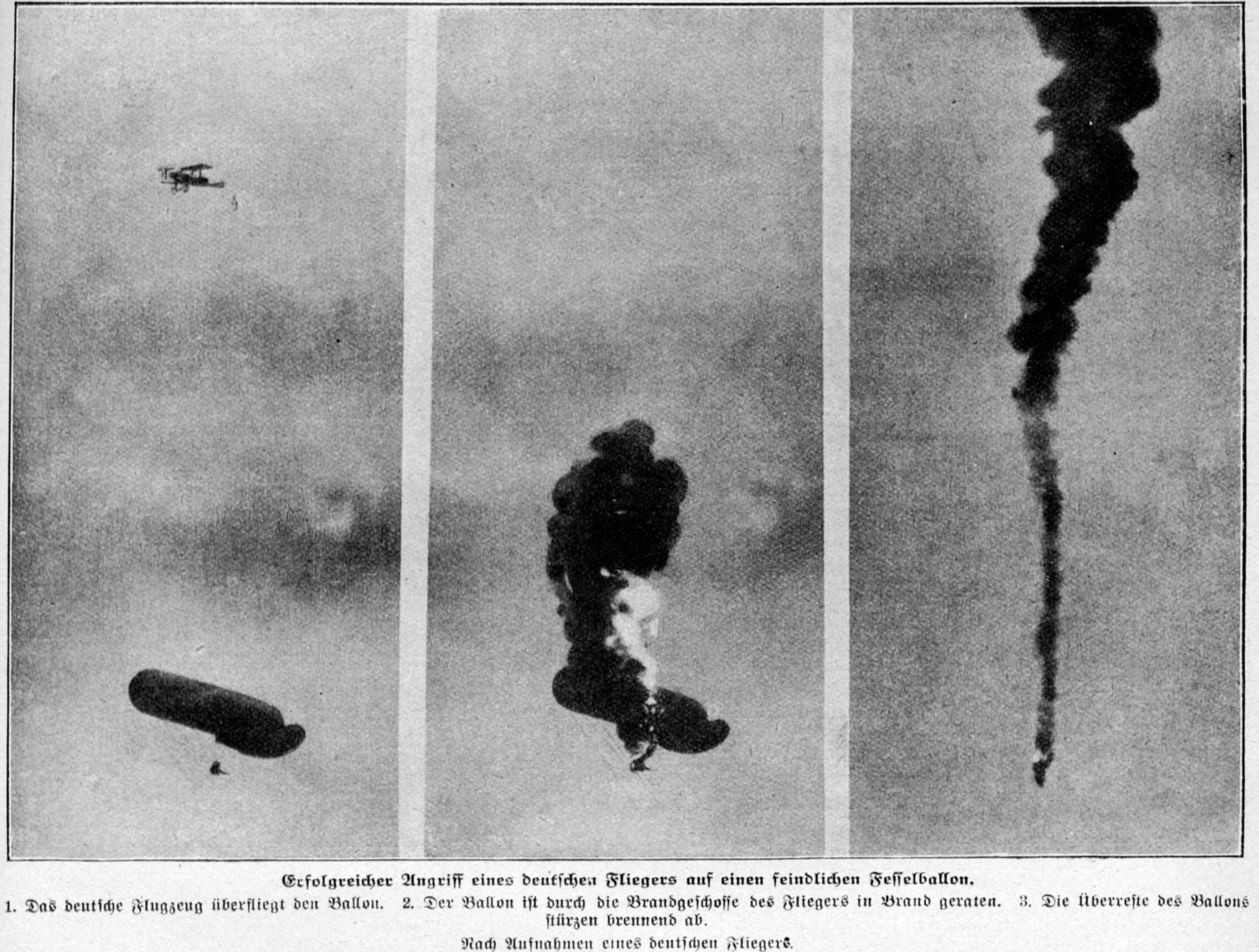

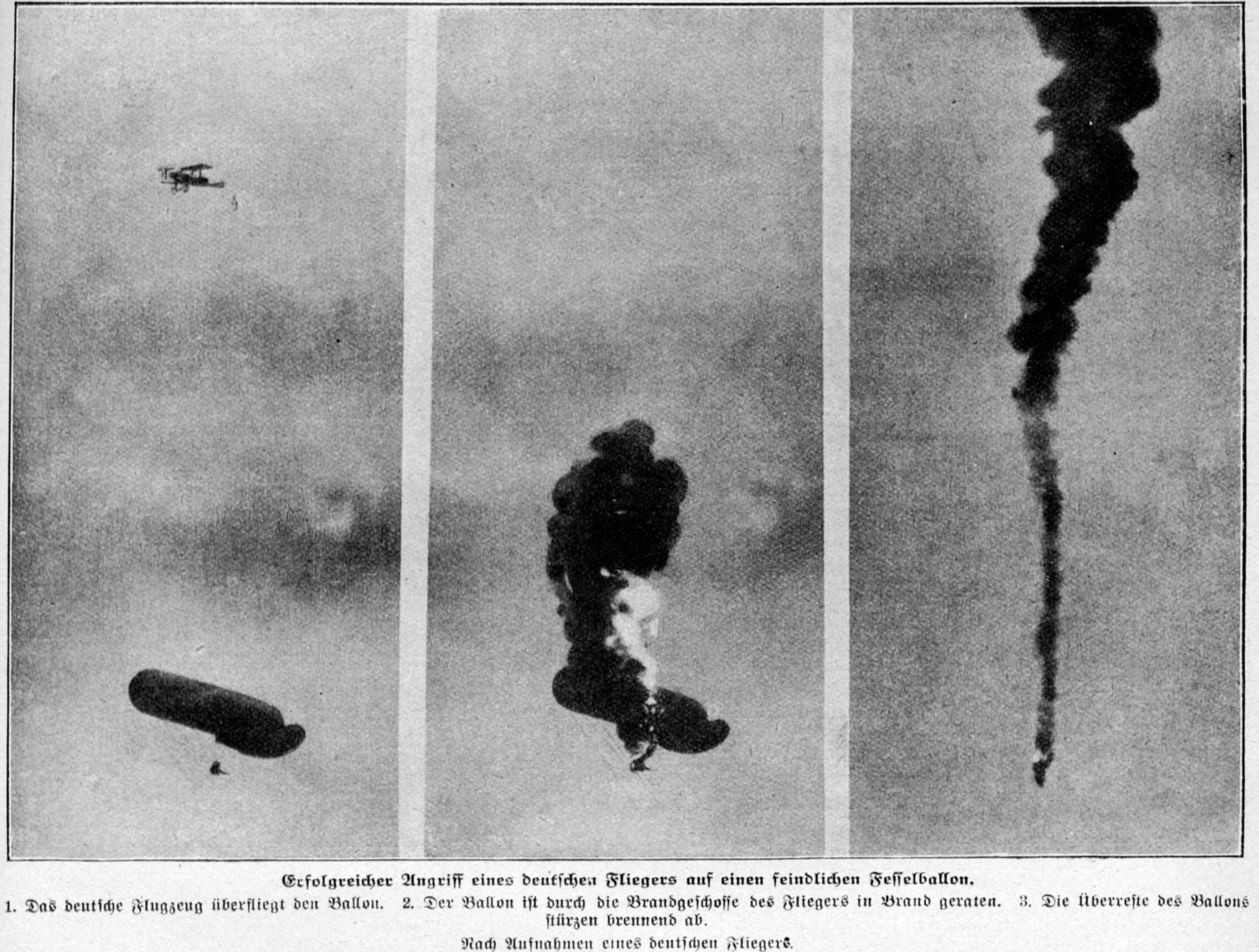

So that’s land and sea, but what about air – surely command wire initiated explosive devices haven’t been used in the air ? Well, actually they have, over 100 years ago. During the Salonika campaign in 1917, some balloons were used by British Forces as observation platforms. German pilots decided to take on these balloons and shot down several, one pilot alone claiming 18 balloons .

A German aircraft attacking an observation balloon

Lt Finch of the British Army Ordnance Corps was asked to design a charge to be placed on a balloon, and this was to be detonated electrically when an enemy plane was close. He placed a 500 pound ammonal charge in a 60 gallon galvanised water tank and “the balloon went up” carrying the explosives connected to a 3000ft cable, on 28 November. As a German plane approached, piloted by Oberleutnant von Eschwege, it was exploded, and the enemy aircraft’s wings were blown off, killing him. Here’s some details of the aftermath which is interesting:

There was no celebrating, no cheering. The British official history states:

He came to his end as a result of a legitimate ruse of war, but there was no rejoicing among the pilots of the squadrons which had suffered from his activities. They would have preferred that he had gone down in fair combat.

Eschwege was given a burial with full military honors; six British pilots carried his coffin to the grave. A message was dropped over Drama airfield:

To the Bulgarian-German Flying Corps in Drama. The officers of the Royal Flying Corps regret to announce that Lt. von Eschwege was killed while attacking the captive balloon. His personal belongings will be dropped over the lines some time during the next few days.

The next day a German plane dropped a wreath and a message:

To the Royal Flying Corps, Monuhi. We thank you sincerely for your information regarding our comrade Lt. von Eschwege and request you permit the accompanying wreath and flag to be placed on his last resting place, Deutches Fliegerkommando.

A similar but unsuccessful device was used on the Western front.

So there we have electrically-initiated command-wire explosive devices on land, on sea, and in the air.

To close though, my favourite Salonika campaign story. Nothing to do with explosive devices! The British army’s efforts in the multi-national campaign in Salonkia did not go unnoticed. The Serbians, ostensibly the British Allies in the Macedonia campaign, of which Salonika was a part, were most grateful for the arduous efforts of their allies. They therefore proposed a glamorous medal be minted, something like “the Glowing and Glorious Order of the Serbian White Eagle”. They proposed awarding 5000 of these medals to a random selection of the British forces who had taken part as a visible sign of their gratitude. The superior Headquarters of British Forces in the Eastern Mediterranean was based in Cairo and an overworked staff officer in G1 was tasked with providing a list of the assigned honourees. Somewhere along the line the list was accidentally put in the wrong envelope. As a result, a list of 5000 soldiers across the Near East, many of whom had hardly even heard of Salonika but who “had not yet received a typhoid injection” were surprised to receive a flowery, ornate and shiny medal through the post – and 5000 hardened Salonika veterans probably got another typhoid jab.

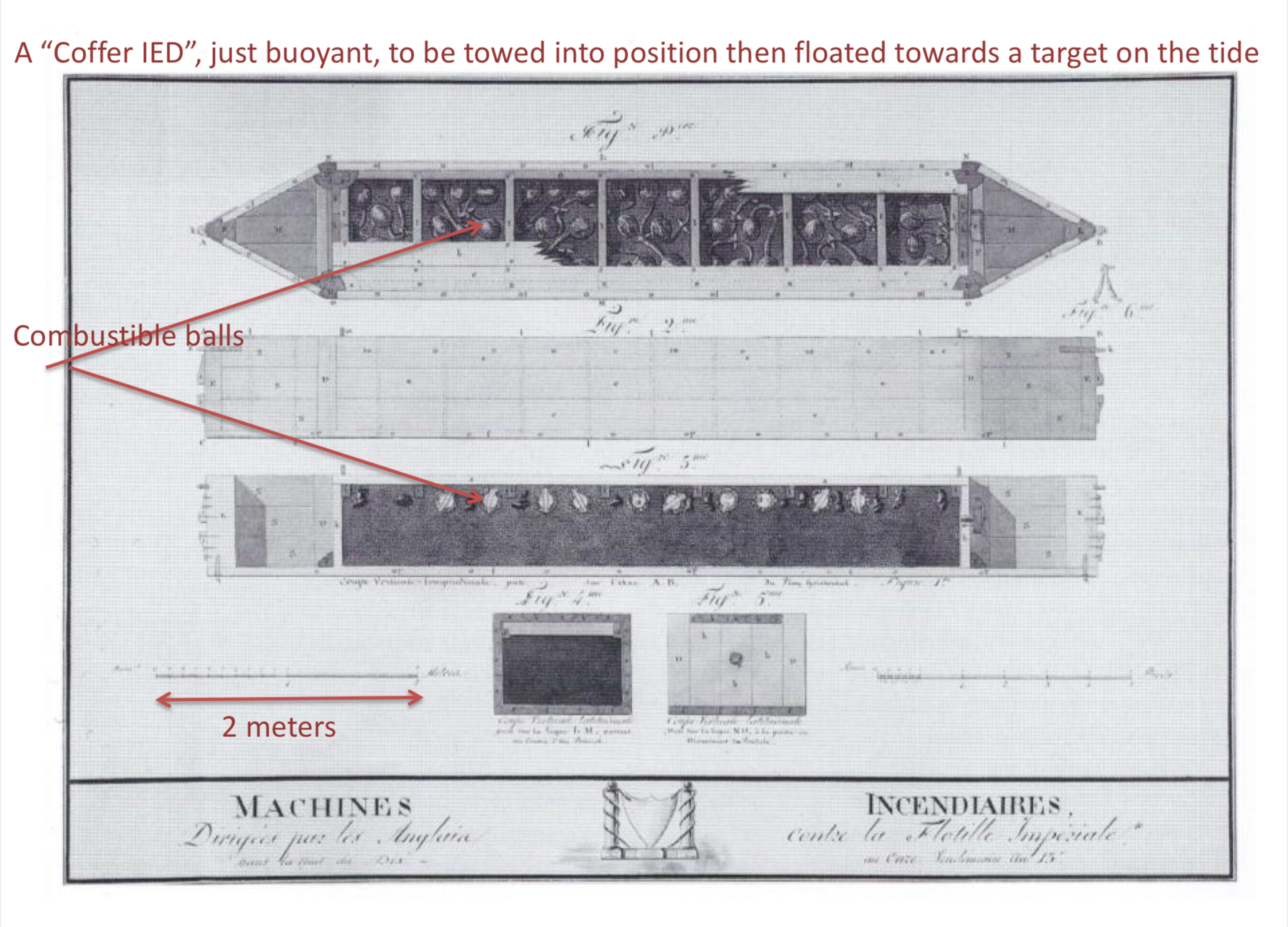

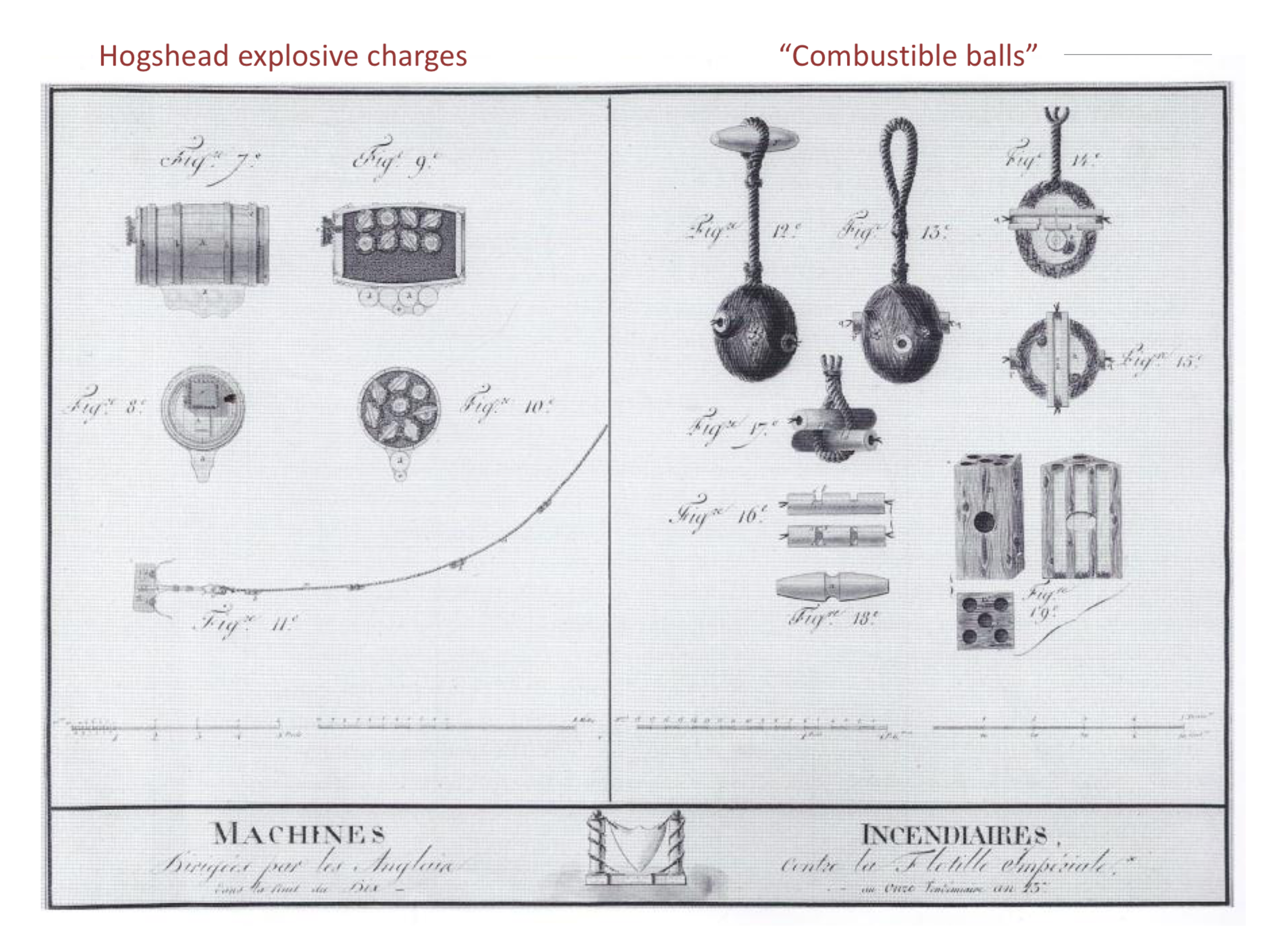

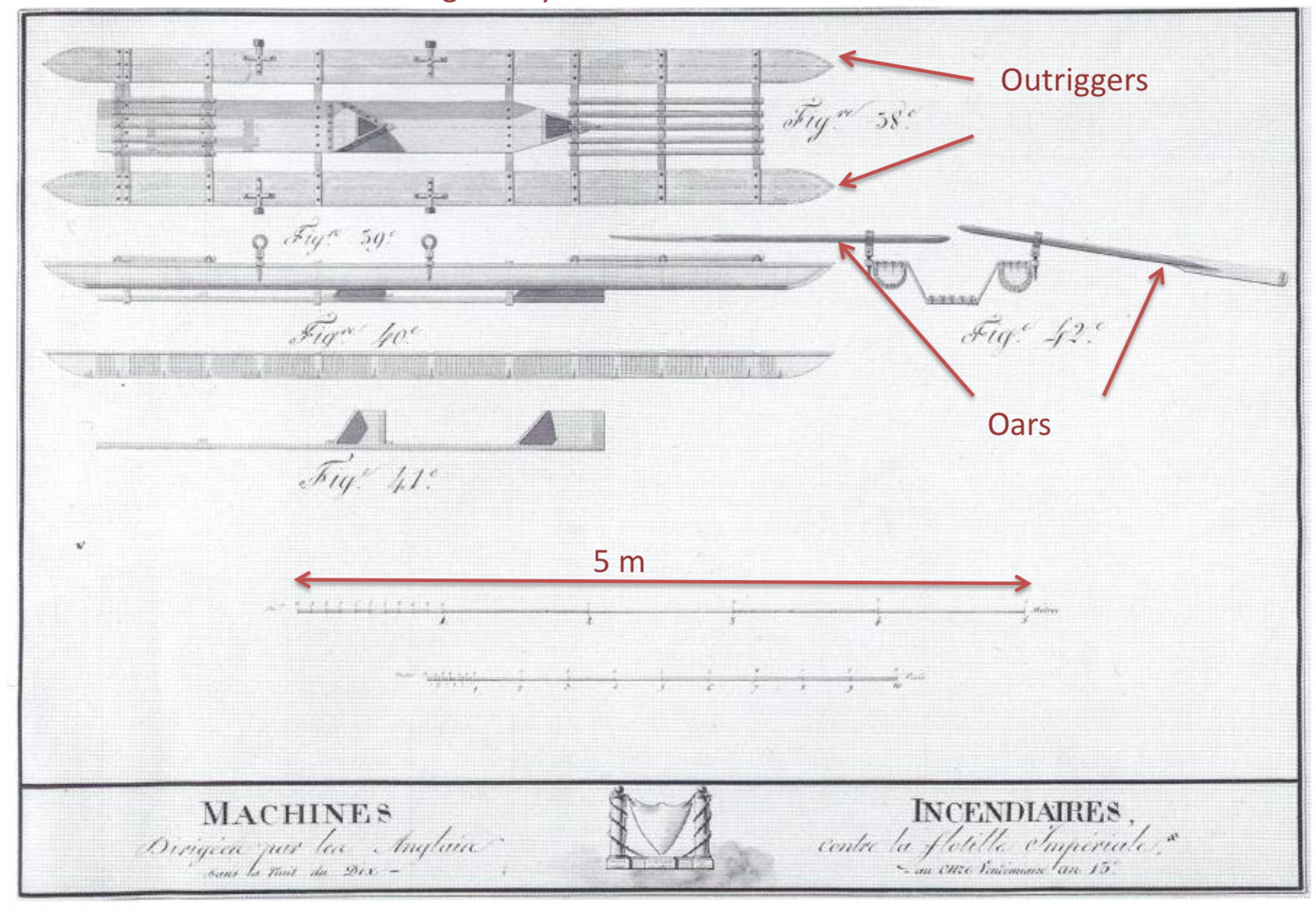

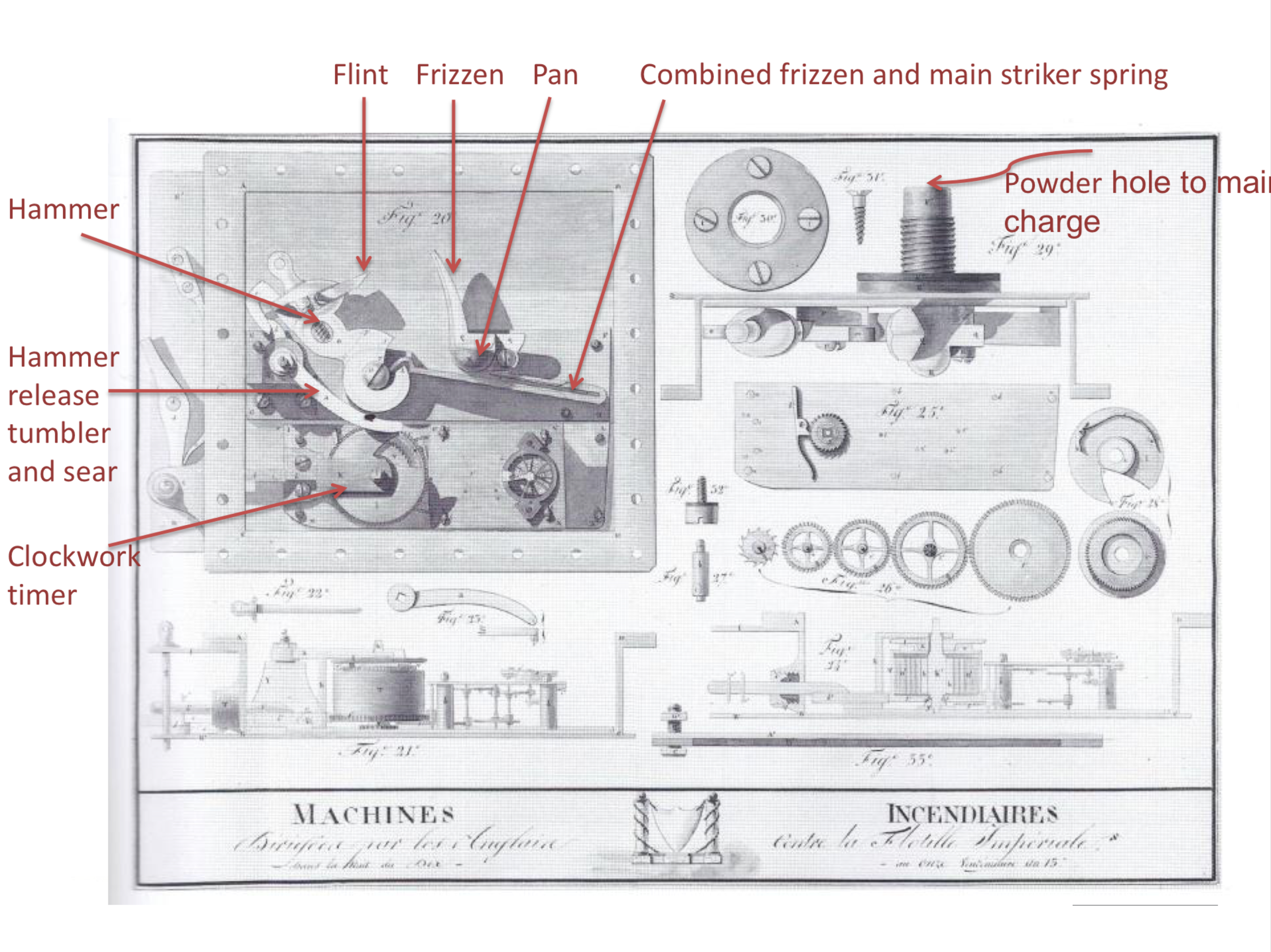

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.

This clockwork initiation mechanism was attached to a main explosive charge. The main charge was a large sealed canoe shaped pontoon, described as a coffer. Two of these were attached to make a barely buoyant twin raft with a rowing position in the middle.