In some of my previous blogs I wrote about the first command wire IEDs occurring in the US Civil War, then had to correct myself as I found earlier examples in the Crimean war and then again earlier incidences by both Immanuel Nobel and Samuel Colt.

Well, I keep finding other perhaps earlier references as I dig into this and follow this “historical alley” and it’s really quite interesting and clearly things go back further in time than I had appreciated. Here’s some extracts from what I’ve been digging up.

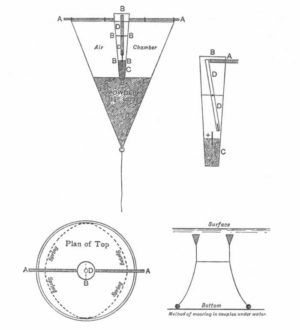

It starts with some further exploration into the efforts of Samuel Colt, the American industrialist and arms inventor. Separate from his efforts developing small arms, Colt for many years attempted to get the US government interested in a system for defending the US coastline which he referred to as his “Submarine Battery” which were essentially water-borne command initiated sea mines. I attempted to try and find the inspiration for Colt’s efforts and the science on which he based his submarine munition technology.

I have in earlier blogs discussed the parallel work of Immanuel Nobel (father of Alfred Nobel) who developed command initiated sea mines for the Russian Navy at about the same time. It would appear that another 19th century military industrialist, this time the German Werner von Siemens was also developing very similar technologies perhaps a few years later in 1848, compared to Colt and Nobel who worked on their versions in the early part of the same decade. What is unclear is if these three entrepreneurial military technology developers were aware of each other’s developments. Siemens’s devices were used to protect Kiel from Danish naval attacks in 1848.

But pertinent to the subject of electrical initiation of IEDs is a letter written by Benjamin Franklin in 1751 to Mr Peter Collinson of the Royal Academy in England which states

I have not hear’d, that any of your European Electricians have hitherto been able to fire gunpowder by the Electric Flame. We do it here in this Manner.

A small Cartridge is filled with Dry powder, hard rammed, so as to bruise some of the Grains. Two pointed Wires are then thrust In, one at Each End, the points approaching each other in the Middle of the Cartridge, till within the distance of half an Inch: Then the Cartridge being placed in the Circle (circuit), when the Four Jars (galvanic cells) are discharged the electric Flame leaping from the point of one Wire to the point of the other, within the Cartridge, among the powder, fires It, and the explosion of the powder is at the same Instant with the crack of the Discharge

I wonder if we can call this the first electrically initiated IED? Albeit manufactured with pure science in mind rather than as a weapon.

Inspired directly by Franklin, the Italian Allessandro Volta wrote to a colleague in 1777 describing how he had fired muskets, pistols and an under-water mine by means of his electrical piles. I suspect this was the first electrically initiated IED actually intended as a weapon.

Volta’s Italian compatriot, working on a telegraph, Tiberius Cavallo then took a step further in 1782 in the following manner

The attempts recently made to convey intelligence from one place to another at a great distance, with the utmost quickness, have induced me to publish the following experiments, which I made some years ago. The object for which those experiments were performed, was to fire gun-powder, or other combustible matter, from a great distance, by means of electricity. At first I made a circuit with a very long brass wire, the two ends of which returned to the same place, whilst the middle of the wire stood at a great distance. In this middle an interruption was made, in which a cartridge of gunpowder mixed with steel filings was placed. Then, by applying a charged Leyden phial to the two extremities of the wire, (viz. by touching one wire with the knob of the phial, whilst the other was connected with the outside coating) the cartridge was fired. In this manner I could fire gunpowder from the distance of three hundred feet and upwards.

I think this may effectively be the first command wire initiated IED.

The next issue to be dealt with was waterproofing electrical cable and a variety of attempts were made using a range of substances including india rubber, varnish and tarred hemp. The Russians appear on the scene. Baron Schilling Von Canstadt was a Russian diplomat in Bavaria who took great interest in scientific developments. On his return to St Petersburg in 1812 and driven by war with France, Schilling Von Canstadt developed electrically initiated charges that could be fired across a river, the cable running through the water, with a carbon arc initiator. These were demonstrated in 1812 but do not appear to have been adopted by the Russian Army. Later after the Russians entered Paris after Napoleon’s defeat he undertook a number of similar experiments crossing the Seine. Here’s a description of him demonstrating a command wire IED to Tsar Alexander I

Once Baron Schilling had the honor to present a wire to the Emperor in his tent. He begged his Majesty to touch it with another wire, whilst looking through the door of the tent in the direction of a very far distant mine. A cloud of smoke rose from this exploding mine at the moment the Emperor, with his hands, made the contact. This caused great surprise, and provoked expressions of satisfaction and applause.

His successor, Tsar Nicholas I was fortunate to escape serious injury in 1837 when an electrically initiated charge was used on a demonstration to destroy a bridge but the demonstration went wrong and the charge detonated prematurely or with larger effect than expected.

The next on the scene were the British. Colonel Pasley of the Royal Engineers was inspired by a newspaper report of the accident in Russia and working with the electrical scientist Wheatstone developed insulated cables and platinum filament exploding detonators around 1839.

Also in the 1830s, American scientist Robert Hare developed “galvanic techniques” for quarry blasting.

Enough for now – some time in the future I’ll return to Colt’s submarine battery, but will state here that as a 15 year old boy in 1829 it appears he had his first success in initiating an explosive charge under water.