The image above shows a small artillery piece. The artillery piece is actually improvised and how it got put together, how the ammunition was provided for it and how it was used is a story worth telling.

In 1899 the Boxer Rebellion erupted in China. This was a violent anti-foreign, nationalist uprising. In June 1900 large numbers of Boxer fighters converged in Peking. Many foreigners sought refuge in an area known as the Legation quarter, where a number of foreign legations had their headquarters and residences. The Chinese government response was at best ineffectual and at worst complicit, eventually declaring war on the foreign powers. The Legation quarter, remarkably was then under siege for 55 days, occupied by the foreign legations working together in defence and by a number of Christian Chinese. There were about 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers from eight countries, ( Japan, Germany, Russia, Great Britain, France, Italy, USA and Austria-Hungary) and about 3,000 Chinese Christians present in the blockaded area. The foreign powers, represented by an Eight nation alliance shared responsibility for the defence of a makeshift perimeter and waited for relief columns.

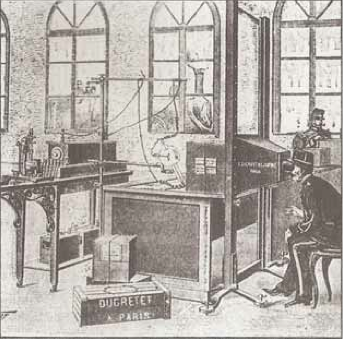

From a “Standingwellback” perspective the siege had some interesting aspects – electrically initiated (improvised?) mines were placed in the major navigable river to prevent European ships from accessing Peking by a water network. I’m hunting out details of these. The Boxers also tunnelled extensively under the legations and a number of extremely large IEDs were initiated, killing hundreds.

For the defence of the legation area, the defending legations had a number of small arms and a very small number of heavier weapons. These heavier weapons included the following:

- The U.S. Marines brought an 1895 model Colt machine gun. Its firing system used a lever action device not unlike that of the Winchester and similar rifles but mechanized to fire 450 rounds per minute. The Marines’ Colt machine gun was mounted on wheels as if it was a miniature cannon. If these guns were not raised or mounted in some way, their gas-powered firing mechanisms gouged holes in the ground, spraying the gunners with dirt. This trait gave the gun its nickname of the Potato Digger.

- Another machine gun, a Maxim, came with the Austrian troops.

- The British legation had a Nordenfelt four-barreled, rapid-firing, 1-pounder gun. The Swedish-designed piece was originally made for naval use and was capable of piercing the boilers of attacking torpedo boats. The Nordenfelt was prone to jam after every four shots,

- The Italians brought another 1-pounder gun.

- The Russian contingent had a large quantity of 9 pounder shells, but had omitted to bring a 9 pounder gun.

Considerable ingenuity was required to maximise the defensive firepower. When the Italian one-pounder piece ran low on shells, Gunner’s Mate Joseph Mitchell of the USS Newark manufactured new ammunition. Pails full of spent enemy bullets were gathered up and handed to Mitchell. Using discarded shell casings and improvised propellant, he melted the bullets to make new projectiles.

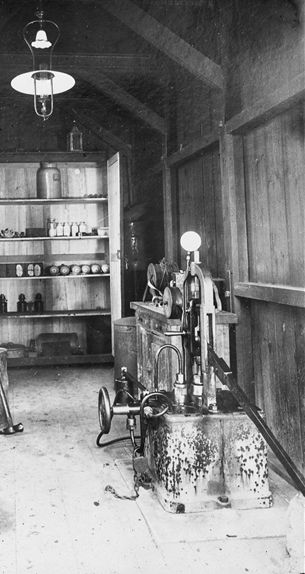

At one point an ancient muzzle-loading bronze cannon barrel was recovered (some reports say it was dug up, others that it was found in a junk shop). Now, Gunners can be an inventive bunch, (some of my best friends, etc) and Mitchell, the US gunner, worked out that they could fire improvised grapeshot from this old bronze cannon. Things were that desperate. Then someone realised that the bore was the same diameter as the “useless” Russian 9-pounder ammunition. The barrel was roped to a stout roof-beam and wheels from an Italian gun carriage. The 9 pounder rounds were taken apart, the propellant stuffed down the muzzle with the projectile rammed on top, it became a remarkable effective weapon and perhaps crucial the defence.

Loading the International Gun

Chinese solders and Boxer forces built barricades and advanced them foot by foot, encircling the legations ever tighter. Weapons fire from the Chinese was often constant – artillery, small arms, firecrackers and bricks lobbed over walls. The defenders returned fire with what they could. So here we had a barrel found by the British, on an Italian carriage, fired by American gunners, with Russian shells. So while some called the improvised artillery “Old Betsy “ or “the Dowager Empress” it became best known as the International Gun. It played a crucial role in maintaining the defences. It remains today in the US Marine Corps Museum, I believe. I’ll have to zip down to Quantico on my next US trip to see it.

Roger Davies

Roger Davies