Modern terrorism today, where it occurs in the West, frequently revolves around terrorists obtaining innocuous materials from which they make explosives and IEDs. Over recent years Police in the UK and elsewhere have engaged with pharmacies, chemist shops, fertiliser suppliers and others seeking support from the proprietors to report suspicious acquisition of explosives or other items for IED components. On occasion in the last few years legislation has been discussed which might limit the availability of such things as acetone, peroxide and sulphuric acid. These modern concerns are sensible and a useful “flag” set to trigger – on occasions, in the last few years, successful police operations have interdicted terrorist attacks by being alerted when a terrorist attempted to buy components or precursors for an IED.

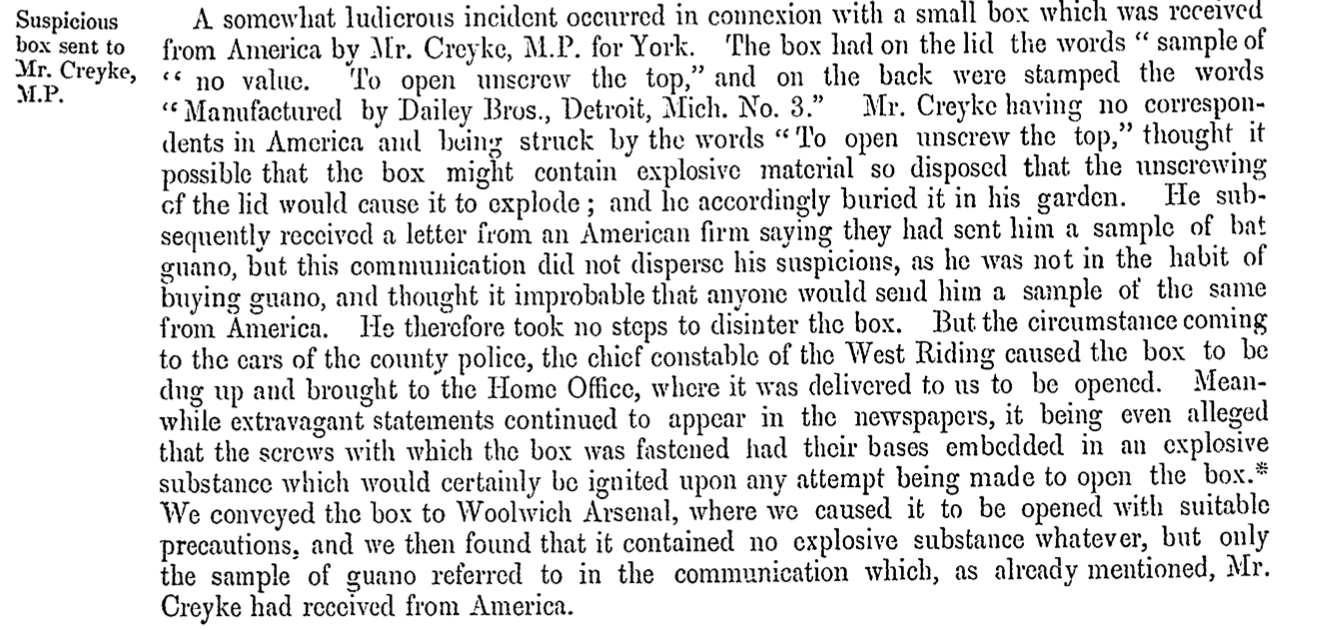

Readers of this blog will know that I have a theme of seeking older patterns for what we regard as modern characteristics of terrorist use of IEDs, and there are useful antecedents here. I have being studying the court transcripts of historical trials and there is a nice example here:

In the 1880s and 1890s, terrorist IEDs were quite common in major European cities like London and Paris. This meant that the public were aware of the threat, suspicious of certain activity, and police operations were significant, as was their engagement with suppliers of material that might be of use to those with evil intent.

In 1894, two Italian anarchists, Guiseppe Farnara and Francis Polti were prosecuted for possession of explosives with intent to endanger life and property. The two had been attempting to make IEDs with pipe work purchased from engineering companies , to be filled with explosives manufactured from supplies purchased from chemists. The two Italians had tried to purchase iron piping from an engineering firm run by a Mr Cohen at 240 Blackfriars Road in London. One of the managers who worked for Mr Cohen, Thomas Smith, was suspicious of the Italians and the purpose for which they were acquiring the pipe. He persuaded the Italians to return to the shop at a future date when he would have the piping and end caps ready for them. Mr Smith then reported his suspicions to the local police station, and a team of police officers subsequently “staked out” the premises waiting for the Italians to return. Smith was also able to elicit that the suspects were having other pipework supplied by another company, Millers, of 44 Lancaster Street Borough Road. The police were able to follow that line of investigation too. So, Cohen’s establishment was staked out and Smith was given clear instructions on how to engage in a dialogue with the terrorists. The terrorists were put under a major surveillance operation , involving quite a number of police and followed around London. I’m intrigued as to what we would regard as a highly proficient surveillance operation, comparable to today’s surveillance operations – for example, a police sergeant described how a terrorist, carrying the IED components from Cohen’s, was followed on to an omnibus. a total of four police officers, part of the surveillance team, operating undercover, were also aboard that same bus. One sat in the seat immediately behind the suspect. After leaving the bus, the suspect apparently carried out anti-surveillance drills, looking for tails. At this point he was arrested. Subsequent investigation of the suspect’s living accommodation found explosive recipes and IED manufacturing instructions along with other chemicals including a bottle of Sulphuric Acid. The instructions were disguised as a recipe for “polenta”, and appear to be a chlorate explosive of some kind which would be initiated by the addition of acid.

The terrorists had approached Taylor’s drug company of 66 High Holborn and bought two pounds of Sulphuric Acid in a bottle.

In the trial the government explosive chemist, Dr DuPre gave expert evidence to the manufacture of the explosives. Col Majendie, the Chief Inspector of Explosives and the nearest equivalent to the head of the bomb squad also gave evidence. Interestingly the court transcript is deliberately vague, I think, when describing the initiation system, and the “polenta” explosive.

My view is that the device would have been designed to be thrown, and initiated when the device hits a target, so in effect was a very large impact grenade, such as the device used to assassinate the Tsar a few years earlier. But something more sophisticated is possible. Readers might wish to refer to some early blog posts about similar devices.

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2011/11/7/the-tsar-and-the-suicide-bomber.html

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2013/12/5/the-ied-technology-of-propaganda-of-the-deed-1884.html

http://www.standingwellback.com/home/2012/10/5/the-curious-death-of-louis-lingg.html

I’m also intrigued by the use of the word “polenta” to describe a yellow chlorate based mix or compound, which seems to have similarities to these Irish chlorate based explosives that were encountered in the 1920s.

From this one case we can see that a population who were aware of IED threats in 1894 were able to report suspicious acquisition of components and that the police were able to act on those tips and plan subsequent detailed surveillance operations.