A shorter gap between blog posts than usual, as I am prompted by responses to the last one about a railway IED in 1880. This one is about a series of three IEDs all targeting the same train, all carrying Tsar Nicholas II on a journey from the Crimea to St Petersburg in November 1879. The attack also allows me to explore once again the concepts of tactical or operational design, which describes how, why, what and when an IED plot is developed and instigated and the factors which constrain or provide opportunity to the development of a terrorist plan.. It also allows me to dissect in more detail why railway IED attacks have seemed attractive over the years.

The group concerned was the revolutionary group Narodnaya Volya. Read upon them if you have time, elsewhere. The sub groups concerned with this “triple” plot are in interesting mix of revolutionaries, peasants and engineer/scientists. In 1879 Narodnya Volya “passed a death sentence” on the Tsar in August 1879 for all the reasons you can read about elsewhere. It then came to their attention that the Tsar, who used the railways extensively to travel throughout Russia, would be travelling from the Crimea where he had a “summer residence” at Livadia, all the way North to St Petersburg. They therefore could predict, somewhat, his route. Here we come to the issue about railways, that when you look at it, is obvious but needs pointing out. Railways are attractive to terrorists because:

- The railway provides a location, somewhere on its length, where a target will present itself. The terrorist knows that the target will be at any specific point along its length at some point, between point A and B, at some perhaps unknown time. So it’s a location where the target “will” present itself with a degree of certainty, and the manner of that presentation (in a railway carriage) is also known. This is a factor a terrorist can exploit.

- In many circumstances, trains are scheduled by a time table. so again the terrorist has a factor he can exploit to a greater or lesser extent. This may give him options for detonating the device, either by timer, or by a victim-operated (train operated booby trap) switch, or by command, allowing the terrorist to only be present at a firing point for a limited period of time, enhancing his security.

- The lengths of railways lines (in this case hundreds of miles) ensures that the terrorist has freedom to lay a device, when no-one else is around, perhaps at night or at distance from people. Security measures cannot cover hundreds of miles of railway. so there is a freedom of action for the terrorist to exploit. In essence every dark night and in every remote location the authorities are forced to relinquish control of the railway.

- The nature of railway lines provides additional factors that the terrorist can exploit. Firstly it is easy bury and hide a device under a rail. secondly the fact that a train is travelling at speed adds to the effect of an explosion which might, perhaps simply rupture the lines – a train will then be derailed, and thus the explosive effects can be added too if needed, so as well as explosive damage there is the kinetic energy release of a train crash. Trains have a large mass, and a high speed, potentially, and these are again factors for the terrorist to exploit in terms of energy utilisation, especially on a bridge or embankment.

- Some other factors, which might appear trivial but which can be important. The railway line can usually be found easily by the terrorist -“Go to station A and walk up the line a particular distance.” The rail system itself is a mode of transport for the terrorist and the IED. Railways are large constructions and a train can usually be seen approaching from a considerable distance, allowing the terrorist some freedoms, and some warnings which can again alert him and allow him to be in a dangerous firing point for a limited period of time. The noise of a train at night also provides this “signal” to a terrorist, which can help them.

In this case, the Narodnaya Volya, as was sometimes their wont, decided on three separate IED attacks on the train as it carried the Tsar from the Crimea, northwards to Moscow and on to St Petersburg at different points in its journey, providing a degree of built-in redundancy in their plot. Interestingly it was known that there had been a plot ten years earlier in 1869 to attack the Tsar’s train in Elizavetgrad with explosives. so the “concept” of such an attack was known to the revolutionaries. In effect they had a template half formed in their mind already.

The group had a “man on the inside’, employed as a railway-guard near Odessa who was able to provide a degree of information. This probably included the fact that actually the Tsar’s train traveled in convoy with at least one other train, one carrying his entourage, with the Tsar in the second train (according to some sources there were three trains and he traveled in the third). This ruled out the sort of attack described in my earlier blog post about the attack in UK, which was designed to be initiated by a train, because that would simply hit the first train. Thus the attacks on the Tsar in the second or third train had to be by command initiation. Three subgroups were formed, one for each attack. They were supplied with over 200 pounds of dynamite made by their technical expert Nikolai Kibalchich in his apartment on Nevsky Prospekt in St Petersburg. Kibalchich carefully tested the explosives and the other components, using as a power source a Ruhmkorff induction coil – which produces high voltage pulses from a low voltage battery (plenty of good you-tubes on such things)

- At a point on the railway near Odessa, Kilbalchich and four others developed the tunnel or trench to run the wires to an explosive charge under the railway taking two weeks to get it into position. Kibalchich brought the explosives he had made himself in a suitcase. Then, days before the expected attack they got news from the insider that the Tsar wouldn’t be travelling on the stretch of track they had expected. So they packed up, recovered the explosives and abandoned this aspect of the plot.

- At a village called Aleksandrovsk, a village between the Crimea and Kharkhov a second group of five rented a house close to the railway line. With difficulty they dug a shallow trench all the way to the railway embankment, laying an electrical cable. It seems the circuit was faulty and when the circuit was closed nothing happened, and the Tsar’s train passed over unharmed.

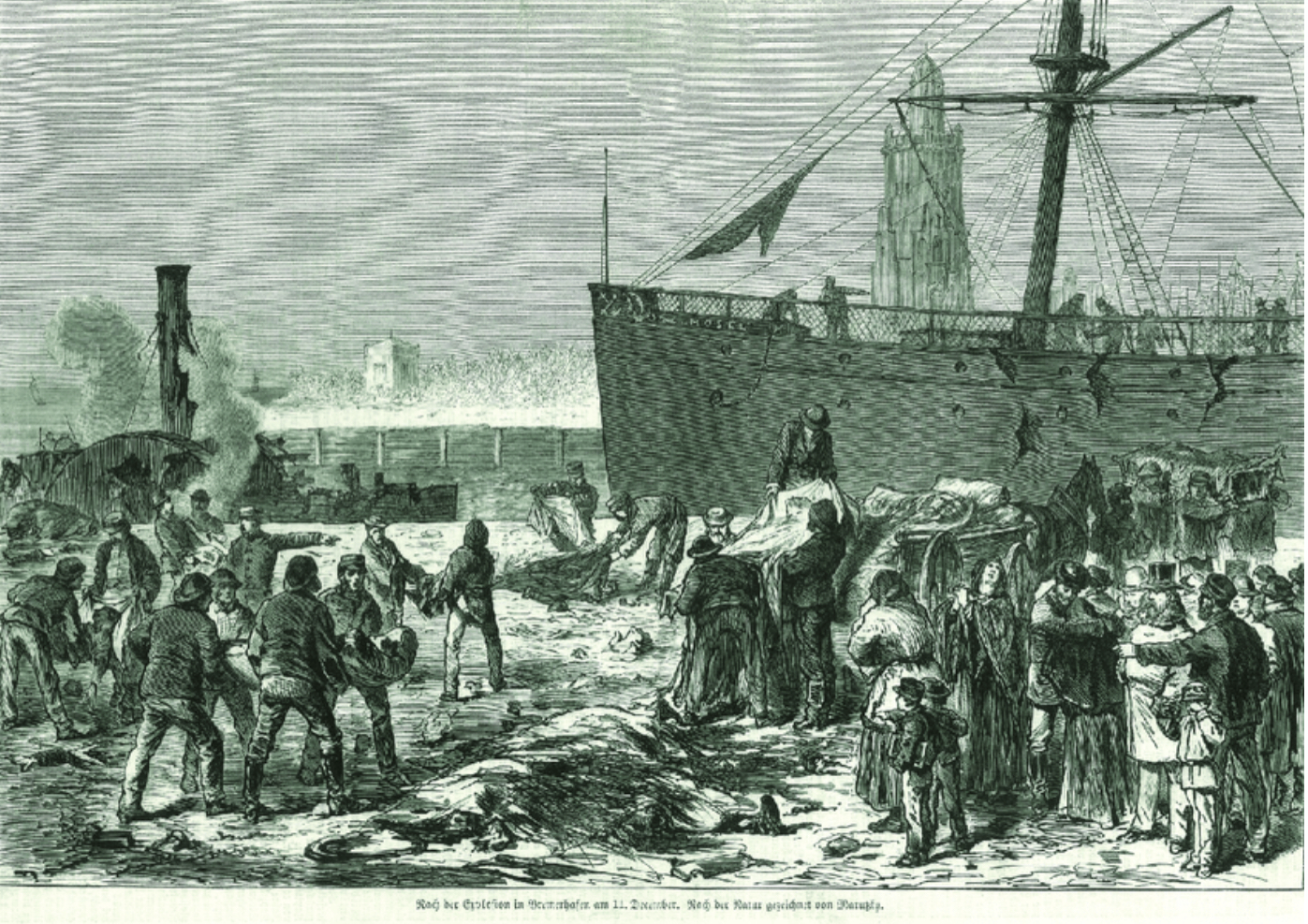

- At the third point, on the approaches to Moscow, the terrorists successfully detonated the device, electrically, under the second train, not knowing that for unknown reasons the order had changed and the Tsar was in the first train which was allowed to pass safely. In this case the device exploded under the baggage train. Interestingly in the “follow up” the police raided the house where the device had been initiated from and remarked how well everything had been “properly camouflaged” to ensure a casual visitor wouldn’t deduce what was going on. More evidence of very careful planning.

So the attacks all failed in their stated intent. But nonetheless Narodnaya Volya claimed a degree of success in terms of derailing the Tsar’s baggage train, and notably announced their pride in planning such a complex operation with care and great diligence. The group saw the attack as a “modern” attack better than confronting the target with a revolver and little chance of escape. Interestingly not long after in 1881 they succeeded in assassinating the Tsar, in St Petersburg, but not by “sophisticated” command devices, allowing their escape but with a bomb simply thrown at the feet of the Tsar, in effect a suicide bomb.

There has been some discussion about how the Narodnaya Volya attacks may have been a preliminary inspiration for other railway attacks that occurred in subsequent decades. But while it may have been something of an inspiration I think that the experience of the US Civil war, where there were a number of IED attacks on railways, and indeed the IED incident I reported on previously in 1870 as art of the Franco-Prussion war, showed the world the potential vulnerabilities of railways to IEDs, well before the Russian events detailed here.

To return to the tactical and operational design concept. I think it’s useful to look in detail at this triple plot, (which failed) compared to the assassination of of the Tsar two years later, which succeeded. An understanding of the design of these plots, and indeed any plot is best elicited (I propose) by asking the following questions of each incident:

- Why did the attack occur here, at this point? The answer is rarely simple, and indeed some of the factors may not even be recognised by the terrorist perpetrator themselves. A few years ago doing a study of roadside bombs in Iraq, an activity I was associated with established 27 different factors which affected the choice of firing point , route of command wire and initiation point.

- Why did the attack occur at this time? Again think beyond just time of day.

- Why was this target attacked?

- Why was this particular device used? Not just the actual device but why this means of initiation, this size, in this container , etc. sometimes an IED is presented to a perpetrator and they have to use it somehow, at other times the device is designed or at least adapted for a particular mission. Understanding which of these options occurred is a useful insight. Sometimes it is driven by some of the other factors.

Answering as many of those questions as you can will give insights into the expertise, resources and skills of the perpetrator, and also provide other valuable information or suggest other leads for the investigator. for the historian too these leads may become fruitful as a result. Comparing the answers regarding these attacks in 1879 and the subsequent successful assassination two years later in intriguing – very different operations, yet counter-intuitively the mission with less detailed planning succeeded. How Narodnaya Volya got from planning meticulously three electrically initiated command devices, over the length of the country (all of which failed in one sense) to a much more ad hoc but successful suicide bombing gives insights that are valuable today, I submit.