In my recent posts about the Irish rebellion in 1803, I suggested that the crucial development seen at the end of the 1700s and early 1800s was the introduction of a metal rocket casing to increase the internal pressure and hence range of the rockets. This assessment is stated as a fact in a number of sources, discussing the development of Congreve’s rockets and their metal bodies. I also assumed that the reports suggesting that it was Emmet’s rockets that were a new development and inspired Congreve were right. There are many historical textbooks which suggest that the designs that emerged in the first few years of the 1800’s were significant developments from the Indian rockets of Tipu Sultan the Indian leader of the Mysore wars. Well, it seems the textbooks, and I were wrong, but in finding this out I encountered something remarkable. Bear with me as I tell the tale.

Firstly, read my last post about how Emmet in Dublin 1803 manufactured his newly invented rockets. Note that the rockets were described as being two and a half inches in diameter, how the maker, Johnstone “consulted a scientific work respecting the way such materials should be prepared” and that “An iron needle was placed in the centre of the tube around which the mortar was tempered, and when the needle was drawn out, the hole was filled with powder”. Also it describes Johnstone using the written instructions which gave the number of blows used to tap the rocket propellant into place with a mallet.

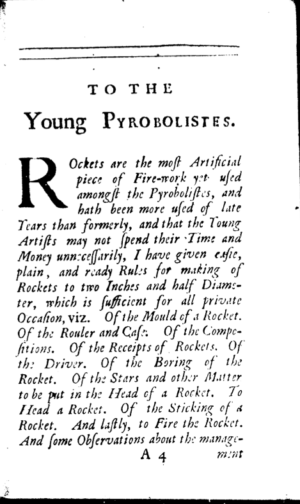

I then went searching for more historical documents relating to rocket development, and found a copy of this document, dated 1696, a hundred and seven years prior to the Dublin rebellion. This is a book written by Robert Anderson, a researcher in ordnance and artillery working for the Earl of Romney, then “Master General of his majesties Ordnance”. All of a sudden things got interesting very quickly.

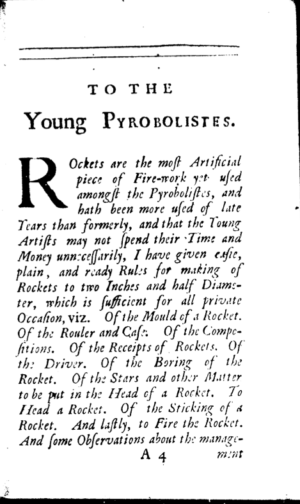

On page A4 of the document, here, it says halfway down, “I have given easie, plain and ready Rules for making of Rockets to two Inches and half diameter.”

I sat up. Two and a half inches? Could that be a coincidence? I dived deeper.

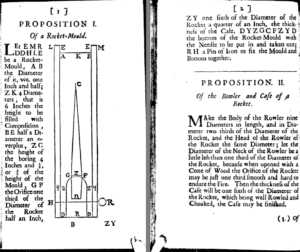

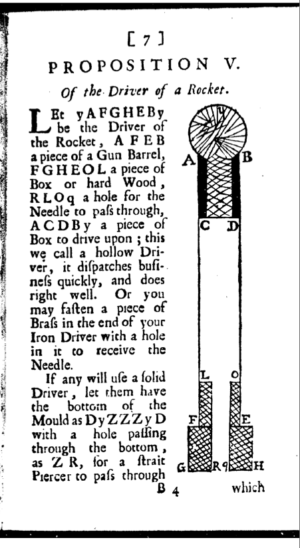

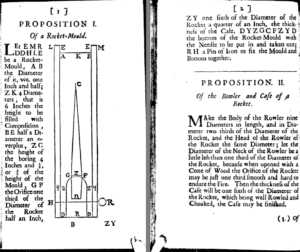

The book first describes how to make the rocket motor moulds. Then on page B2 it describes “the bottom of the Rocket-Mould with the Needle to be put in and taken out:”

Then on page B3 it describes filling the rocket composition with charges and tapping the charges into place “and to every Charge 10, 12 or 14 blows with a Mallet”

So, it is very clear to me that Emmet and his rebels were not making newly developed rockets, learned from the experience of the East India Company’s battles against Tipu Sultan – they were making rockets to the specific design of a two and a half inch rocket design of Englishman Robert Anderson, written over a hundred years earlier in 1696, and using the same document I have in front of me now. Remarkable. I’m not aware of anyone realising that link before now.

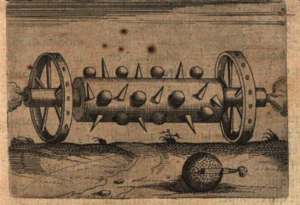

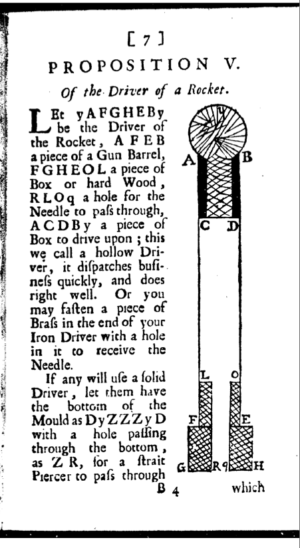

I then went a couple of pages further on and found this diagram. The adjoining text clearly states that the rocket body (AFEB) is made from a piece of gun barrel, and is metal, not pasteboard. Thus the English (and Anderson specifically) had already designed metal rocket bodies over a hundred years before Emmet and subsequently Congreve used the same concept. Many references (incluidng Encyclopaedia Britannica and Wikipaedia) have this wrong ascribing such development to Tipu Sultan a hundred years later.

So, I think this changes our view of history. Emmets’s rockets were not his own development – they were explicitly built from instructions from an English developer over a hundred years old by 1803. Also, Congreve’s rockets were not new in using metal bodies to increase the internal pressure of the rocket motor – that too was achieved by the same developer, Anderson in 1696.

I find it fascinating that rebels today are making their own versions of these munitions, in hidden rooms in Syria, 300 years since Anderson, and 200 years since Emmet copied his designs, constructed them in hidden rooms in Dublin and first used them in a rebellion. Of course today’s rockets have changes in design and in the rocket composition – but in effect, frankly, they are pretty darned similar.