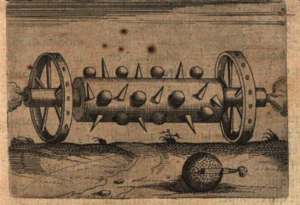

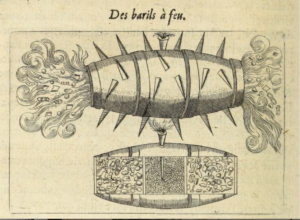

At the moment I’m working on some early seventeenth century pyrotechnic and military manuals again, to re-visit the development of military rockets. (Not everything you have heard about Congreve as an inventor is true!). But in doing so I came across some interesting early IED designs that I had in my archive but deserve a post in their own right. Here’s an interesting IED. Key here is the use of improvised shrapnel and the “spikes” which both add to shrapnel and make the device tricky to move.

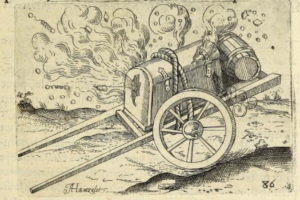

and this – an explosive charge on a cart, so an early VBIED or vehicle bomb. As I have done frequently before, this further discredits the idea that the Wall St Bomb of 1920 was the game changer in terms of the concept of a vehicle bomb use. These images are from a book published in 1630, 290 years earlier. I have listed several other early vehicle bombs here and here . There were also ships (vehicles) and trains pre-dating 1920.