Alchemy is the pursuit of chemical and occult methods to turn base metals into gold, and was an activity pursued with vigour in the 1500s and beyond, into the 1800s even. As proto-chemists evolved so the boundary between “occult magic” and “chemistry” started to emerge. At this time the first ever “high explosive” and indeed the first primary explosive was developed, what we call today fulminating gold or gold fulminate. The German alchemist Sebald Schwaertzer first mentions fulminating gold in literature in his “Chrysopoeia Schwaertzeriana” in 1585. Other texts add more detail in the early 1600s.

For those readers not familiar with explosives, gunpowder is a low explosive, where the explosion propagates through the explosive material, in effect, by heat and flame. In high explosive the chemical reaction occurring is propagated by a shock wave, and fulminate of gold was the first chemical compound isolated which exploded in this manner. Fulminate of gold is also the first inherent explosive compound (gunpowder being a mixture of fuel and oxidizer). As it is ‘sensitive” it is also the first primary explosive.

Gold is one of the most stable elements – it doesn’t react with very much and by implication a compound of gold is easy to turn back into elemental gold, meaning the compounds are unstable.

For obvious reasons alchemists experimented with gold compounds. They mixed gold with other materials and sometimes accidentally produced compounds that surprised them. It’s tricky to make sense of the archaic descriptions, and the peculiar mixture of occult spells (barking mad) and real chemistry.

Fulminate of gold is created by dissolving gold in “aqua regia”, a three to one mix of hydrochloric acid and nitric acid. This creates gold hydroxide. When this is mixed with ammonia, gold fulminate is precipitated. But there are other recipes, which as someone who has a slightly limited expertise in chemistry I simply don’t follow. Real chemists feel free to correct me! This sensitive explosive is then dried, and can be exploded by heating, crushing or scratching. This must have been a remarkable thing when first experienced by alchemists who expected the weird and the wonderful. The chemistry is quite complex and there are a number of related compounds, including (ClAuNH2)2NH and (OHAuNH2)2NH. Essentially though, fulminate of gold is a mixture of various compounds of ammonia and gold, each of them technically a high explosive.

Fuliminate as a term simply means “exploding” . So gold fulminate can be a mix of a number of complex gold compounds including gold hydrazide.

A number of alchemists and later chemists were injured as a result of experiments with fulminate of gold. Even in recent years, the research into exotic gold based catalysts has occasionally caused accidents in modern laboratories where gold fulminate was created.

Here’s the diarist Samuel Pepys describing a conversation on the subject in 1663:

Up and to my office all the morning, and at noon to the Coffee- house, where with Dr. Allen some good discourse about physique and chymistry. And among other things, I telling him what Dribble the German Doctor do offer of an instrument to sink ships; he tells me that which is more strange, that something made of gold, which they call in chymistry Aurum fulminans, a grain, I think he said, of it put into a silver spoon and fired, will give a blow like a musquett, and strike a hole through the spoon downward, without the least force upward; and this he can make a cheaper experiment of, he says, with iron prepared.

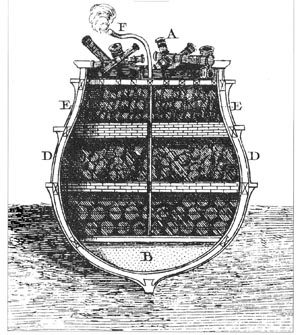

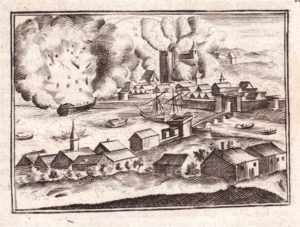

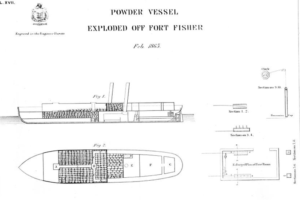

Note that “Dribble” is the inventor Cornelius Drebble, who invented the submarine and coincidentally mercury fulminate. Drebbel had died about 30 years prior to this Pepys reference. Some sources suggest that Drebble was using fulminate of gold as a detonator in IEDs (“petards”) he made for the British at the siege of La Rochelle in 1628. Drebbel was thus perhaps the first man to use high explosives in munitions. Drebble’s father-in-law was an alchemist who lost the sight in one eye from an alchemical explosion. (Pepys had other discussions with Drebbel’s son in law, Johannes Kuffler who was trying to sell an explosive device to sink ships – more on that in a future post.)

The gas produced when fulminate of gold explodes is largely nitrogen. Accompanying the gas is a characteristic violet/purple plume of gold aerosols.