A few days of enforced idleness has given me a little space to think. Inspired by my (off topic) recent post, a book review on the evolution of piston engines in the Second World War I’ve been thinking again about key technological developments in history with regard to explosives and related issues.

To put this blog into context, let me try to make things really simple. An explosion, (whether that be of high explosives or gunpowder) is a chemical reaction, typically a change from a solid to a lot of gas. For about 500 years from about 1000 AD to 1500AD, there was only gunpowder, a low explosive, and this mix of chemical solids could be brought to change to gaseous products with the application of a naked flame which starts essentially a combustion process. So by introducing a naked flame, or equivalent amount of heat, it starts the reaction, and causes the explosion of hot gases. Until about 1500 the only way of igniting gunpowder was by heat or flame. You can see my earlier post about other related technologies here.

But having to have an already burning flame or equivalent is tricky. You can’t disguise it easily. If your “match” is unlit you have too start a fire somehow and that takes time, even more so before the age of boxes of matches and cigarette lighters. All this led to practical challenges in the use of firearms and explosives. The most efficient method until 1500 (and indeed for many years later) was to have ready a slow match burning well in advance,

The time was ripe then in 1500 for a more flexible way of initiating gunpowder, either in a firearm or for an explosive device or indeed nay kind of munition that used gunpowder. There then appears to have been a key turning point enabled by a number of disparate technologies. These include:

- Engineering skill in terms of precision craftsmanship from clock makers. This included the development of skill which creation of relatively fine metal components that could be shaped into a fair amount of detail.

- Advances in metallurgy and associated engineering that led to effective steel springs. The springs become a “store” of energy which can be released to cause sparks with a little ingenuity. To be effective, springs needs to be relatively high in carbon so they don’t lose their “springiness”. In the century running up to 1500, the manufacture of springs became optimised.

- To me (as an amateur blacksmith) there appears to be some clear links and cross over between “door lock” mechanisms that use springs to release levers, and these gun lock systems. As I understand it these engineering developments were also occurring at about this time in history. And of course the word “lock” crosses the gap – in German where these may have been invented the word used for both firearm locks and gun locks is “Schloss”.

Around 1500 the wheel lock was developed, perhaps in Germany or perhaps by Leonardo Da Vinci. The mechanism of the wheel lock is that potential energy is stored in a spring. When the spring (carbon steel enabled by metallurgy) is released, this spring (a coil) typically causes a steel wheel to turn around a spindle as in clock technology. The wheel , with a jagged edge turns against a quantity of pyrites, causing sparks to occur. The sparks drop into a container of ignitable material, typically gunpowder in our case. In preparation to ignition a key is used to tension the spring, which is held on a latch. That spring can be held indefinitely, with only the release of a latch needed to initiate the mechanism and whatever combustible is placed next to it. When the latch is released by a trigger, the wheel spins and another spring loaded lever pushes the pyrites into contact with it. Interestingly the “wheel” also needs to ideally be carbon steel to get the best sparks, so the development of these two key components were driven by clock makers developing springs for their mechanisms using carbon steel, and understanding how energy could be released from a spring and applied usefully. After all, engineering is often about how energy is turned from one form to another.

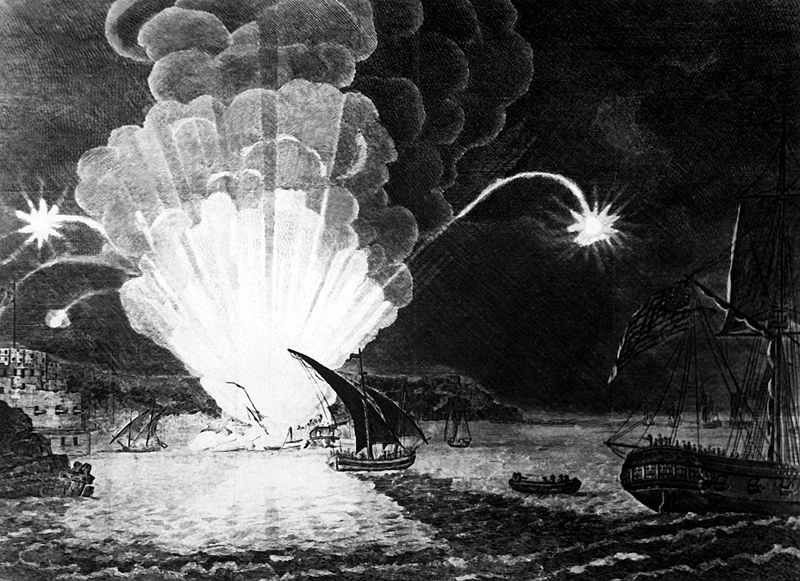

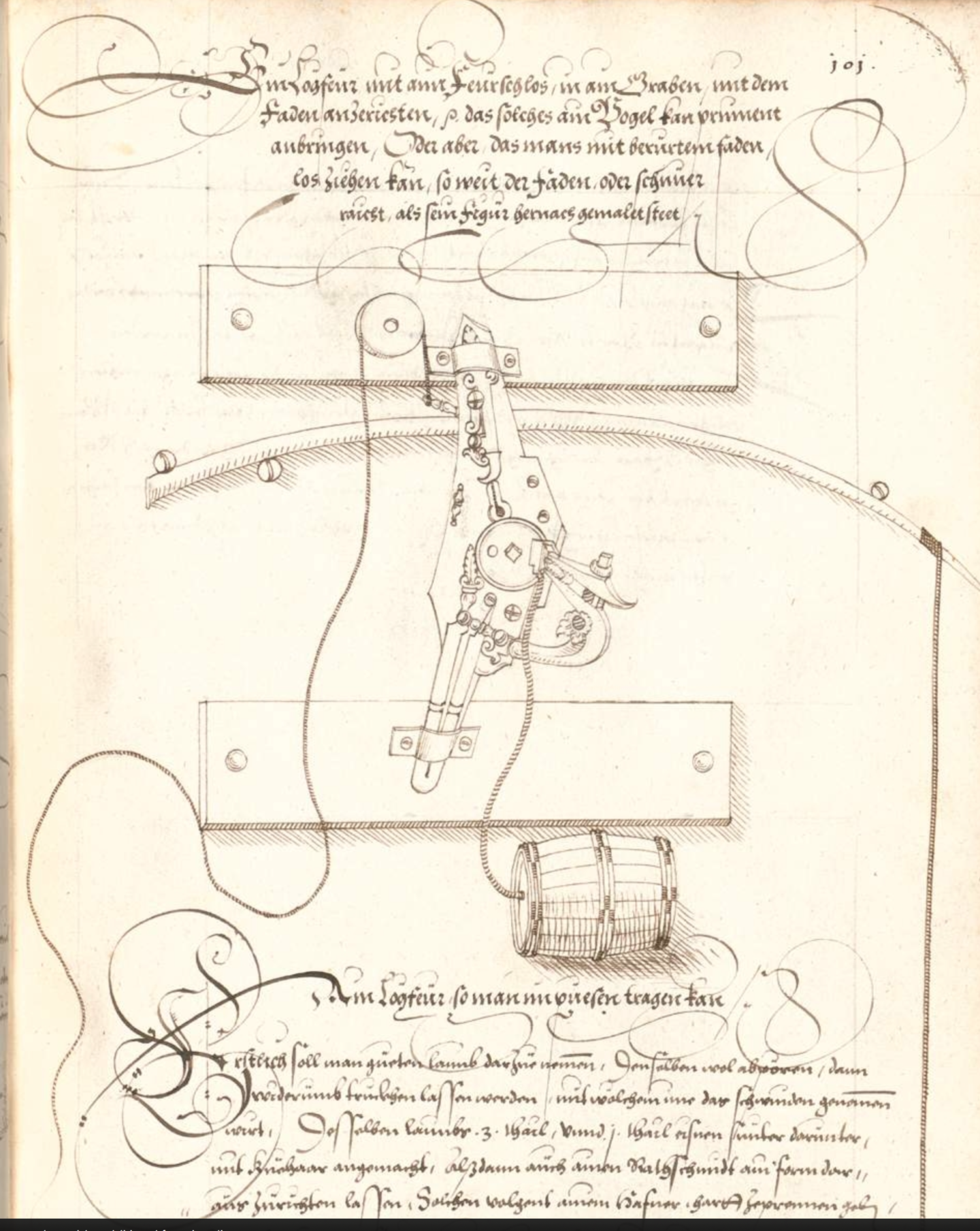

I’ve written before about a lovely diagram from the 1580s of an IED initiated by a wheel lock , with a fantastic picture I found in a book in the British Library. That post is here, but I’ll repeat this diagram below for convenience – it’s one of my favourite historical IEDs. One doesn’t need to understand the writing to work out what’s going on – note the string attached to the trigger, the wheelock mechanism and the fuze leading to a barrel of gunpowder.

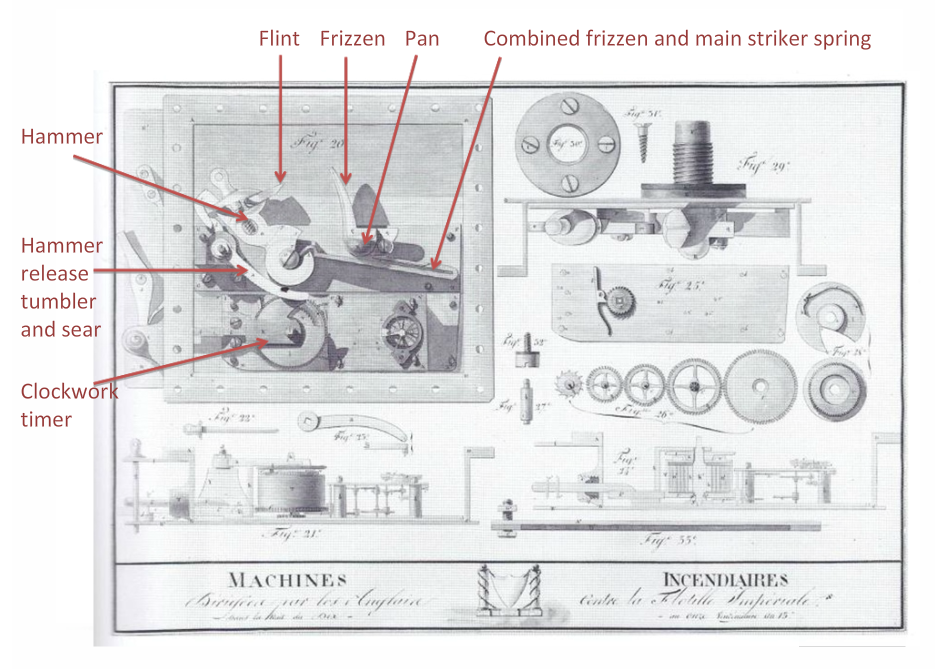

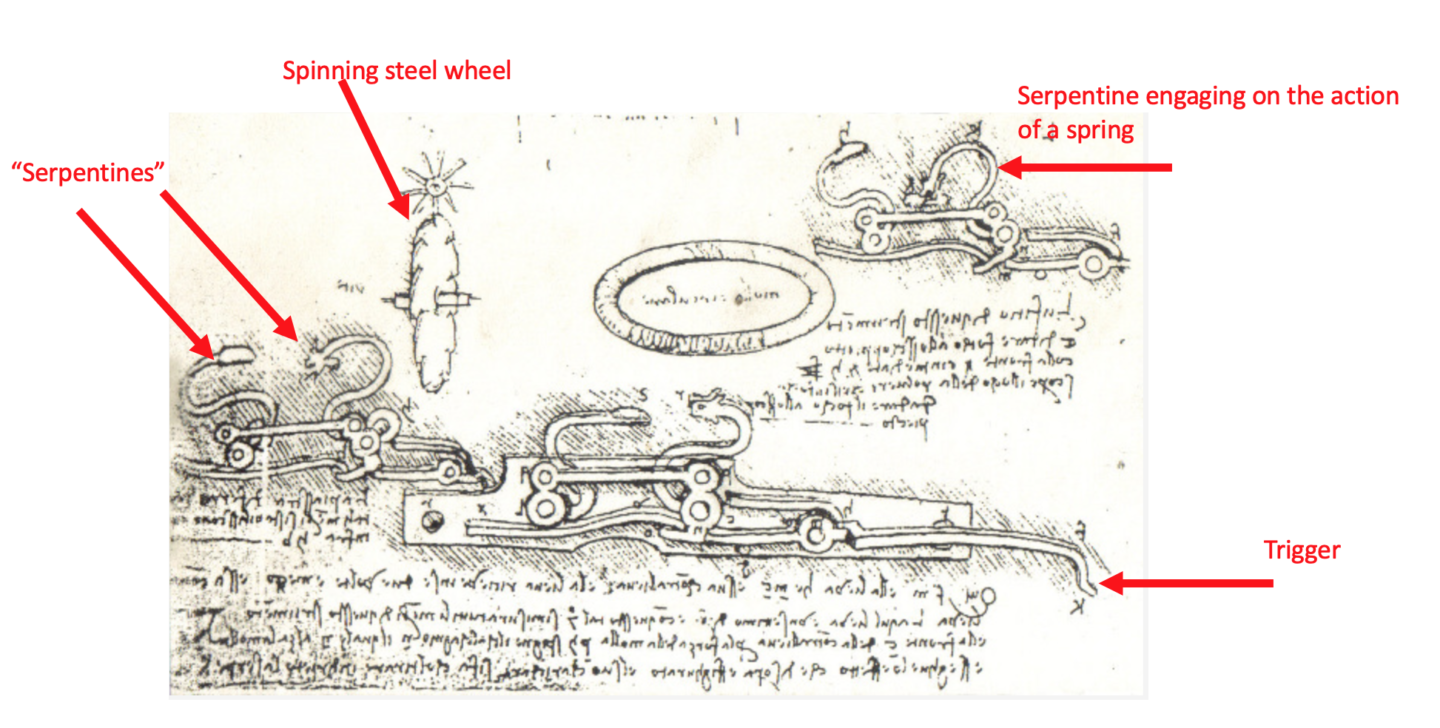

So this image was a wheel lock initiated IED from 1582, and I wanted to find an earlier example. Some sources suggest that Leonardo Da Vinci was the “inventor”, so I’ve been hunting for Da Vinci diagrams. Here, below, is one from the “Madrid Codex” . Whether Da Vinci actually designed this or was simply copying a design made by a German inventor is an issue for the academics. If I’m honest I can’t quite understand the diagram (and also the accompanying text!) but I have picked out some key points. Let me at least point these out to you:

- The Trigger, is at the lower right hand side. Compare this with the trigger above at the top, tied to a piece of string which runs round a pulley.

- There are two Serpentines in the diagram below. A serpentine is best thought of as a lever which acts under the effect of a spring. If I’m honest I’m not certain of the purpose of the left hand one – it could be as a release-latch on the spring loaded steel spinning wheel. The right hand serpentine I think holds the pyrites, and a spring action pushes that down when triggered. “Serpentines” were of course used before wheel locks to hold the burning fuze of a match lock, then press it into the gunpowder when a trigger was pulled releasing it. the second serpentine could though, be a failsafe, duplicate to the first.

- The spinning wheel is shown vertical and isolated but I suspect it was horizontal, but it’s not clear to me how this was held. I’m also not sure what the circular object in the middle is.

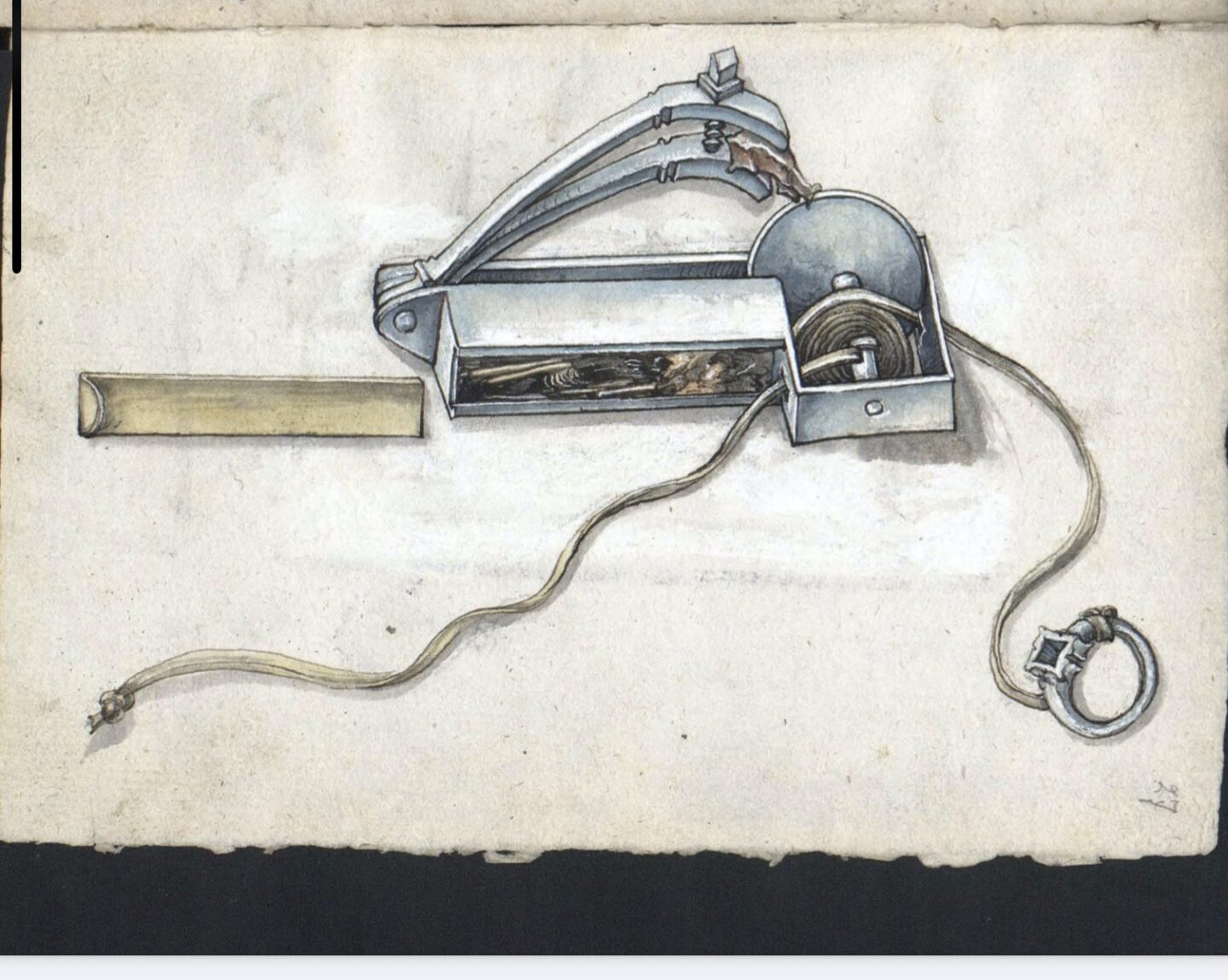

In doing some more digging I found a couple more interesting diagrams that are worth showing in the context that I think they may not be to ignite explosives, but rather to light tinder, which in effect meets the same requirement. Perhaps these “mechanical tinder igniters” were precursors to the wheel lock. They date from the first decade of the 1500s, right in the early days of match locks and I have lifted them from the “Loffelholz Kodex”. Here’s the first:

This is really a beautiful diagram, from 1505, and I think shows a pocket-sized igniter. A portable “everyday carry” from 500 years ago. The box container contains tinder” or , if you like, gunpowder. The brass slide holds the tinder in a box. A cord is fitted to a spindle, and wound round and round. Also attached to the spindle is a steel wheel, and the serpentine holds the pyrites. The user, with a ring on his finger to which is tied the cord, pulls, the wheel spins, the pyrites is engaged , sparks fly and light the tinder. Replace the tinder with gunpowder, and run the cord as a trip wire and you have a booby trap IED. You can see that with the addition of a clock spring , a release catch to allow the spring to act on the wheel and another spring to engage the pyrites, it is the same idea.

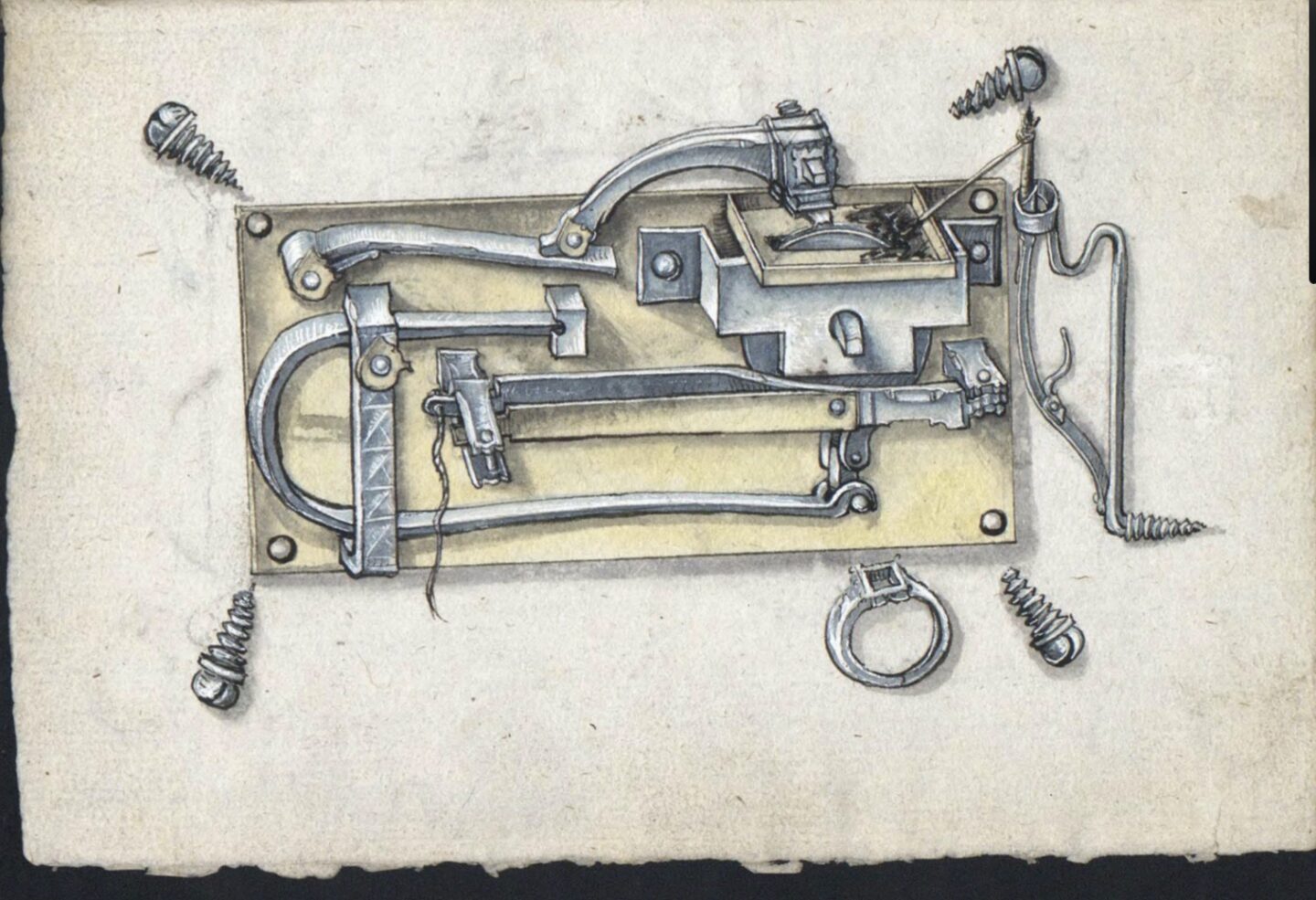

The second diagram is more complicated, and I confess I can’t quite work it out. But it is clearly a wheel lock device for some purpose or other. If you can interpret the action here, please let me know your thoughts. I can see the “wheel”, the tinder box, the serpentine holding the pyrites and one , if not two triggers, but I can’t quite work out the springs. Clearly this is meant to be screwed onto the side of something.

What these inventions do, that previously wasn’t very easy to achieve, are:

- Reliable ignition of gunpowder without the need for a pre-lit burning fuze, allowing concealment in advance. This is a key IED capability. Previously any emplaced device would have been spotted by the smoke emitting from a match, and could not have been left for any length of time.

- Booby trap initiation – using the “string” to release a spring, or pull a spindle, both causing sparks and thence initiation of a charge.

- Command initiation from a distance, again using the string.

- Timed initiation – because a clock could be used to to cause the trigger to be pulled – and it was clock engineers who were developing the mechanisms anyway.

So these are startling new offensive capabilities for explosive devices. As such, the development of the wheel lock had perhaps more of an impact on explosive device design than on firearms. where , in battle at least, the need to conceal a burning match was not an issue. Perhaps there was an impact though on the use of firearms in ambushes and for highway robbers, when firearms could be concealed under a cloak. Such mechanisms in firearms were quickly banned in some countries – again showing the potential for the illicit use of a mechanism such as this for nefarious effect.

As such I think that historically speaking the development of the wheel lock is one of the most significant engineering developments in the history of explosives as it provided several distance new IED capabilities. Wheel locks were expensive to produce so the use of match locks continued for some time – flintlocks which came some time later were simpler and therefore cheaper to produce, eventually phasing out the wheel lock. That development is in itself interesting because it was a “simpler” technology replacing a complex engineered device.

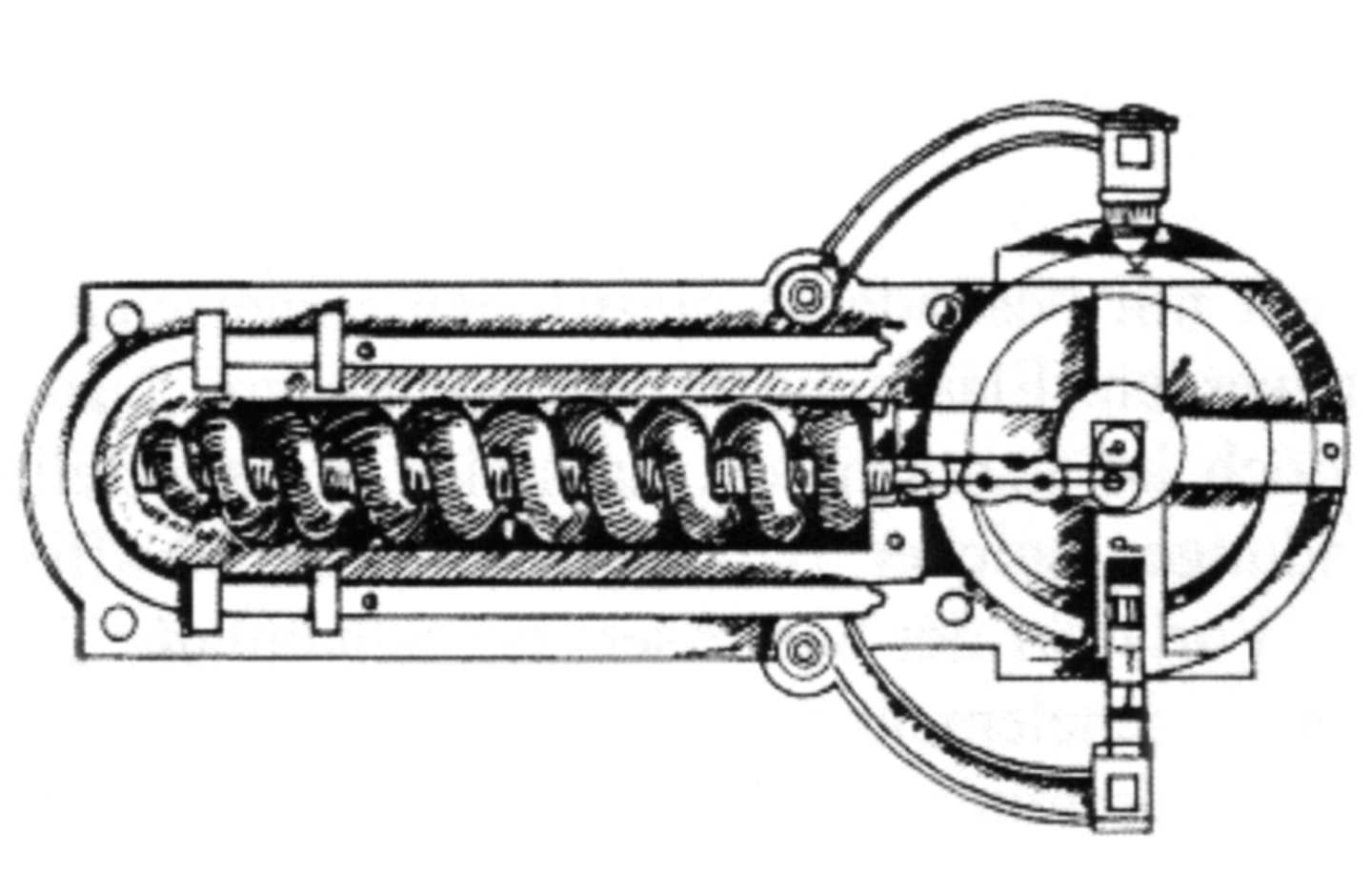

Before I finish, there’s two interesting aside. Most wheel locks used a concentric spiral spring to turn a spindle that ran through its middle. But there’s two other initiating systems , one a variant of the spring construction. This is it below, another Da Vinci Drawng, this from the Codex Alantic and you can see that the spring is a longitudinal coil rather than a spiral, but it still acts on a “wheel” that is perpendicular to the length of the spring.

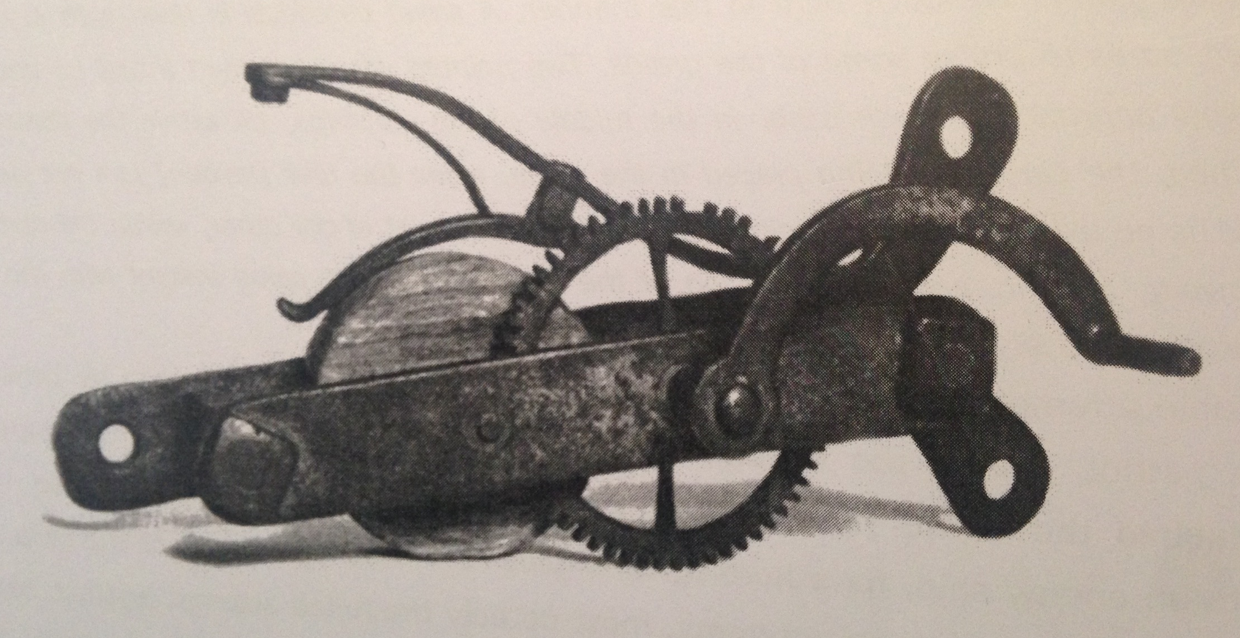

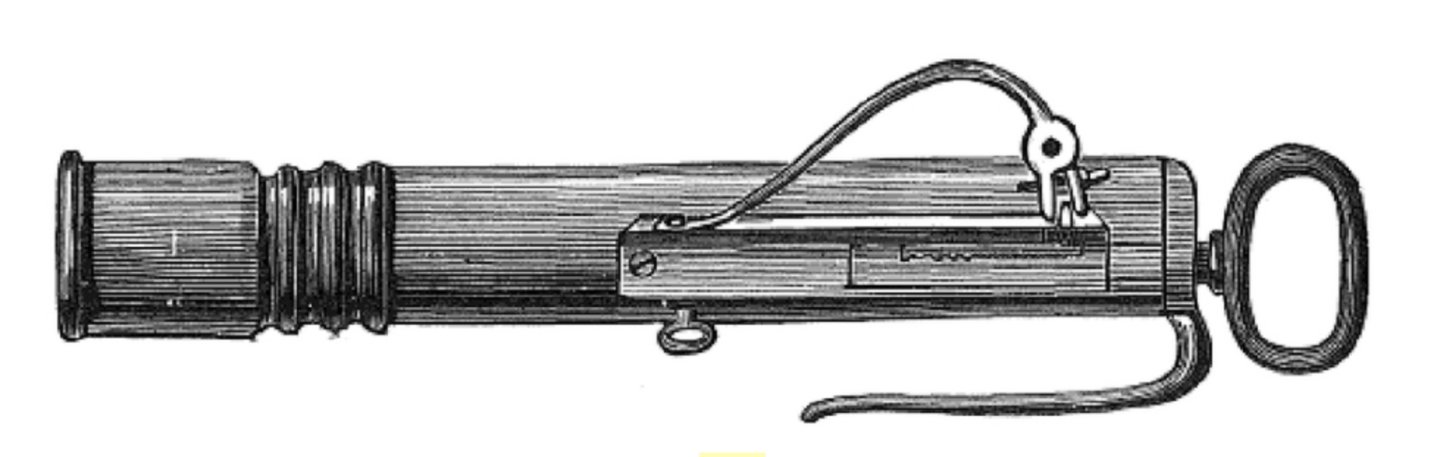

Finally another approach to the same problems this not using a wheel at all but a longitudinal bar of steel pulled so that it scrapes along the pyrites. This is the Monk’s Gun, held in the Dresden Armoury. This dates from somewhere between 1480 and 1550.

Although it has no “wheel” it has the advantage (?) of being somewhat simpler. You can see the “serpentine” holing the pyrites, and the ring on the bottom is pulled to the right, causing the teeth on a steel slide to act on the pyrites producing a spark – hidden behind would have been a touch hole leading to the chamber of this simple gun.