When I started my research into historical IEDs a few years ago, I came across references to “gun locks” used as initiation mechanisms. The “gun locks” are from firearms such as wheel-locks or flintlocks re-purposed to initiate a larger explosive charge.

However I have continued to encounter these mechanisms at every turn of my research. The deeper I dive into historical documents the more I think they were much more common than I had realised. In fact I think they were a usual way of initiating IEDs for about 250 and even for as long as 330 years. I think that’s surprising and worthy of explanation The wheel-lock and its successors, the snap lock, the snap-haunce and the flintlock are essentially spring loaded levers operating around an axis which contrives to place a spark ignition system in direct proximity to gunpowder. In a firearm the “trigger” is pulled by the person aiming the firearm – the pull of the trigger releases the spring-loaded mechanism. In general terms in an IED the trigger is pulled or released by another mechanism such as a lever or a cord. But it is the same mechanism.

The developments of gun locks for firearms were paralleled and linked inextricably with the development of household locks for doors and chests, and the same people made both. There is also a distinct parallel in technological development terms with clock making which saw some significant developments in about 1580 with the development of spring driven rather than pendulum driven mechanisms, and one sees this being a mechanism that enables mechanical timing mechanisms in IEDs for the first time at around this date. But the clock is only a component to release a spring loaded lever, allowing the flint, for example, to strike and cause sparks. One can still see the influence of clock making in fairly modern fuzes, and I think that’s an area for future research, to explore the early parallels of lock mechanics with fuze mechanics. Indeed the language of clocks and explosive fuzes is very similar in describing components – ”fuzes” and “trains”.

I’ve discussed before some of this , in relation to the invention of detonating systems, but here I want to concentrate on the locks and the derived implications to IED design.

Here’s an outline of the technology:

Prior to 1500 firearms were fired with “match locks”. Pulling a trigger caused a slow burning cord, (a “match”) held on an “s” shaped lever to be pushed into contact with the gunpowder charge. In about 1500 the wheel lock was developed as a sophisticated mechanism to initiate a firearm without a pre-lit match. The wheel lock is a spring loaded steel wheel which acts with friction against a piece fo pyrite to produce sparks, pushed against it by a spring loaded lever or “dog”. The resultant sparks land upon the beginning of the gunpowder train. (think of a Bic cigarette lighter, yet the thumb which turns the steel is replaced by a spring). A simple “detent” safety catch is easy to include which prevents the spring loaded mechanism being moved until the device is set up in place. Thus the wheel lock is:

- Safer than using a matchlock where a slow burning fuse (“match”) is introduced to the gunpowder train (not a good idea with a large charge of gunpowder immediately adjacent)

- Able to be left in place for as long as the gunpowder doesn’t deteriorate

- Able to facilitate its containment and concealment (partly due to its small size) within an enclosure, which again a matchlock is not suited to.

- Able to prevent the give-away smell of a burning match and the sight of a glow.

So in IED terms the wheel lock and its successors enable ease of use, concealment and safety, all key aspects for someone wanting to use an IED.

Pyrite is used in wheel-locks rather than flint because flint is too hard and the wheel would wear away rapidly. The wheel-lock is quite a complex piece of engineering and therefore expensive, which would have been a discouragement for the “one time use” within an explosive device.

The snap lock was introduced in the late 1540s. The key to its design is that it is simpler, with less moving parts – simply a spring loaded lever holding a flint that falls on a steel or “frizzen”. There is no wheel to wear out, and much less complexity, meaning that it is cheaper and therefore more likely to be “thrown away” in an IED.

The snaphaunce LINK developed in the 1550s and the flintlock LINK developed in 1620, were basically improvements on the snaplock design , allowing the pan to be covered for safety and to keep out the weather – the essential difference between these latter two is the mechanism by which the pan of gunpowder was uncovered.

So, between 1500 there is a period of 120 years of technological development to get from the original matchlock to the safe, flexible, cheap, easy to operate flintlock. Here’s a video showing in a bit more detail how a flintlock on a firearm works.

From about the 1540s it may have become an economic option to use a gun lock in a “one time use” IED – perhaps from a broken firearm.

The next issue to address is how the trigger is pulled or released to allow the gun lock to fire. There are essentially three principle modes of initiation for IEDs, all based around the fundamental idea that the perpetrator does not want to be near when the device explodes – and the firing lock can enable each one of these three:

- By command from a distance. Simply by tying a cord to the trigger of a gun lock a device can be initiated from a safe distance.

- By a victim’s action. By tying a cord to the trigger and attaching the end of the cord to an attractive object or some other thing likely to be moved, the perpetrator can cause the initiation by a victim.

- By timer. if the firing lock trigger is attached in some appropriate way to a clockwork mechanism, then after a set time, the trigger will be pulled.

The following examples detail use of these three technique from the period between 1585 to 1918 – a significant period of history

In the 1570s the somewhat exotic inventor Ralph Rabbards describes contrivances that require some sort of spring loaded mechanisms to initiate explosives, and at the same time Samuel Zimmerman of Augsberg described explosive devices set off with hidden springs and string. Zimmermann discusses “booby trapping” a chair that will initiate a device when sat on, and booby trapping a “purse of gold” left lying in the street. I’m pretty certain that these devices would have used a gun lock initiator – how else would they have been initiated? The technology was there and there are no other apparent mechanisms available to the bomb designer of the time.

In 1581, the Polish besiegers of the City of Pskov sent a jewelled casket to the occupants of the city of Pskov. The device exploded when it was opened by the Russian defenders. This booby trap mechanisms must have been initiated by a gun lock , adapted and contained in the casket.

This link here, tentatively dated to the 1580s shows 4 command initiated devices, initiated by operators pulling a cord from a distance. One has to assume that the cord was attached to the trigger of a firing lock buried in the barrels on the route of the target convoys. Not much changes does it?

In 1585, Giambelli’s clockwork Hellburner was triggered by a clock provided by Antwerp clock maker Jean Bovy. Now techncialy, that could have been a lever, activated by the clock, which moved a burning match. But I think a gun lock is more likely.

In 1628 Cornelius Drebbell (the inventor of an early submarine) developed floating devices used (unsuccessfully) by the English Navy against the French in La Rochelle. I have found this description of Drebbels explosive devices, written by Charles Bernard in 1628 in the Mercure Francois:

`During the night between Sunday (Oct. 1st.) and Monday, the English shot ten or twelve floating petards for the purpose of setting fire to the royal French fleet. The body of these petards is of white iron filled with gun-powder and floats on a piece willow wood, through which a spring is made, which when it encountered the bows of one of the royal ships, took effect, which consisted simply in this, that it threw water into the ship with much power; all the others were captured as they floated on the water and did no harm.’

So, my assessment is this – the iron cased charge is mounted on the floating wood platform, some form of spring powered lever acts on the device when it comes into contact with the enemy ships. I think the most likely technology of the time which could have utilised that spring action is to release the trigger of a gun lock. I’m happy to consider other solutions but to me I’m now fairly certain. One historian has suggested that Drebbell, who was known to have dabbled in alchemy, may have used the first ever high explosive, the primary explosive Gold Fulminate (discovered in 1602) – but I remain unconvinced. Occams Razor suggests to me a gun lock.

This diagram below from about 1630, shows a clear representation of a booby trap with a basket of attractive objects , within which is a firing lock tied to one of the top objects – lift the attractive object, pull the cord and the firing lock will cause the device to explode. Look carefully and you’ll see the lock at the bottom.

In 1645 we have this description of two IEDs, each clearly using a firearm lock attached to clocks.

In 1650 we have this device, using a pistol firearm lock, initiated by the pull of a string.

In 1764 we have a postal device that utilised a booby trap using a firearm lock.

In 1776 and 1777 The American revolutionaries used systems that instinct suggests to me were similar to Drebbel’s devices of 1628, but develped by David Bushnell. Buchnell also followed Drebbels lead in submarine vessel ideas.

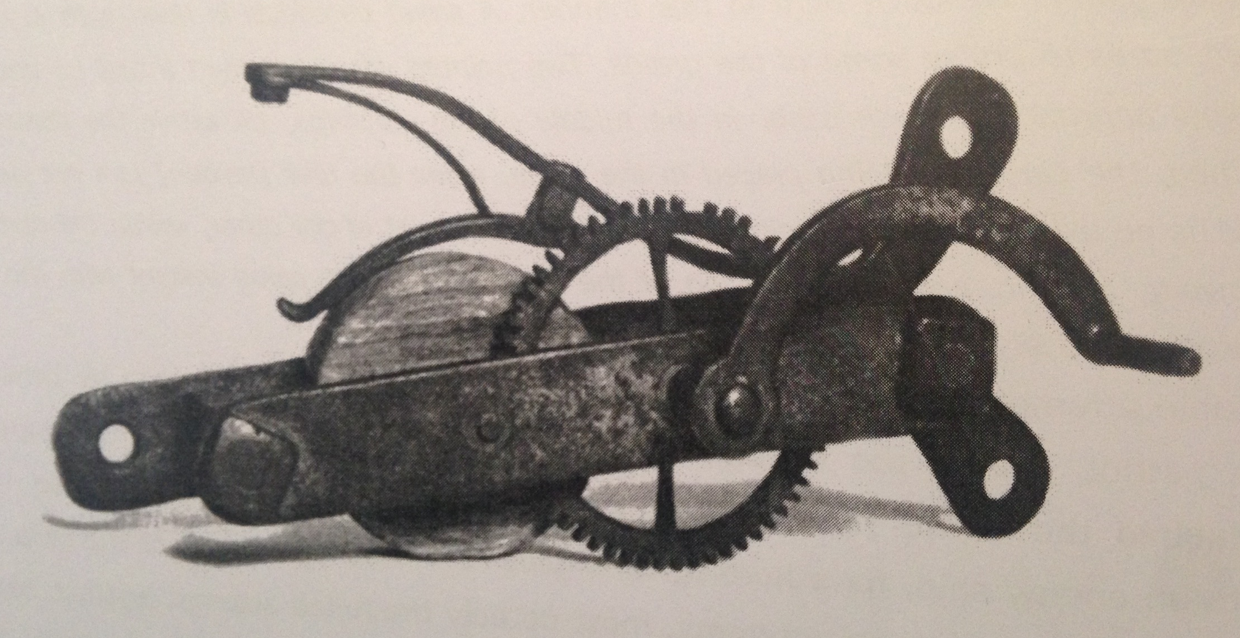

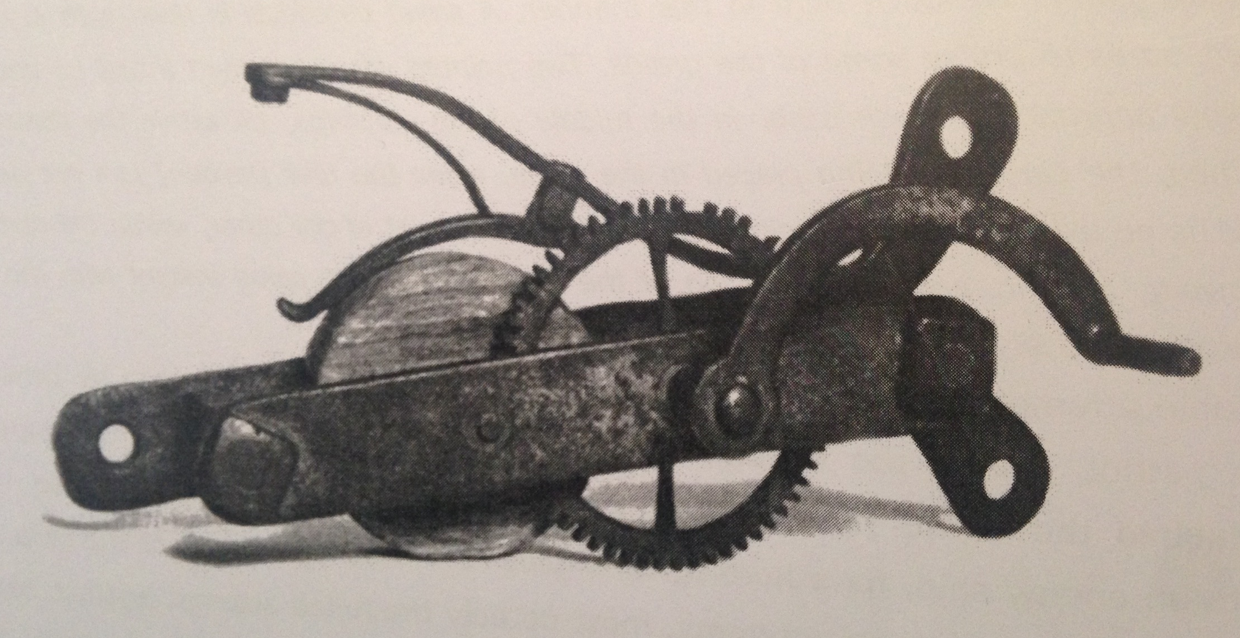

Here’s part of the timing mechanism that Bushnells famous “Turtle” submarine was meant to fasten to the bottom of HMS Eagle. The timing mechanism’s gears ultimately tripped a flintlock mechanism to fire a gunpowder charge. (Photo John Wideman)

Bushnell also used floating explosive charges with levers on the outside designed to be pulled when they came into contact with ships, very much like Drebbels devices of 1628.

This image is a replica of a Bushnell IED that was floated down a river towards the British ships. The lever on the outside causes a flintlock on the inside lid of the barrel to be activated when the external lever comes into contact with the side of a ship, or a cable is pulled in some manner.

This image below is of an original revolutionary IED, the inside of the lid of the barrel, showing the flint lock mechanism held in place, to be activated by the lever on the outside. The flintlock shown appears to be from a British made “Brown Bess”.

(My thanks to John Wideman for allowing me to reproduce these images from his book “Civil War Torpedoes” where these pictures provide context for his very detailed and excellent work of later devices.)

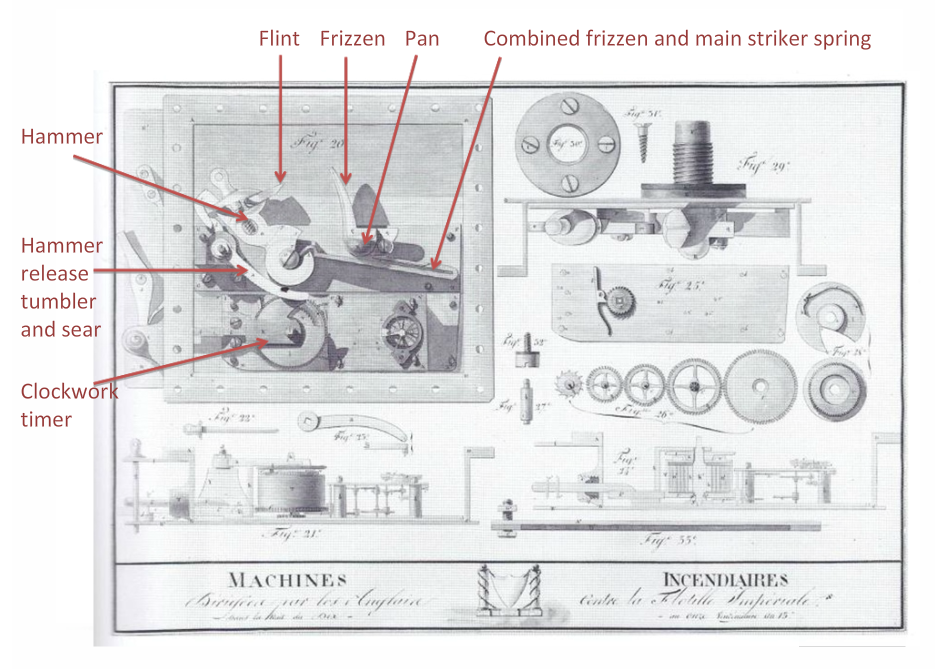

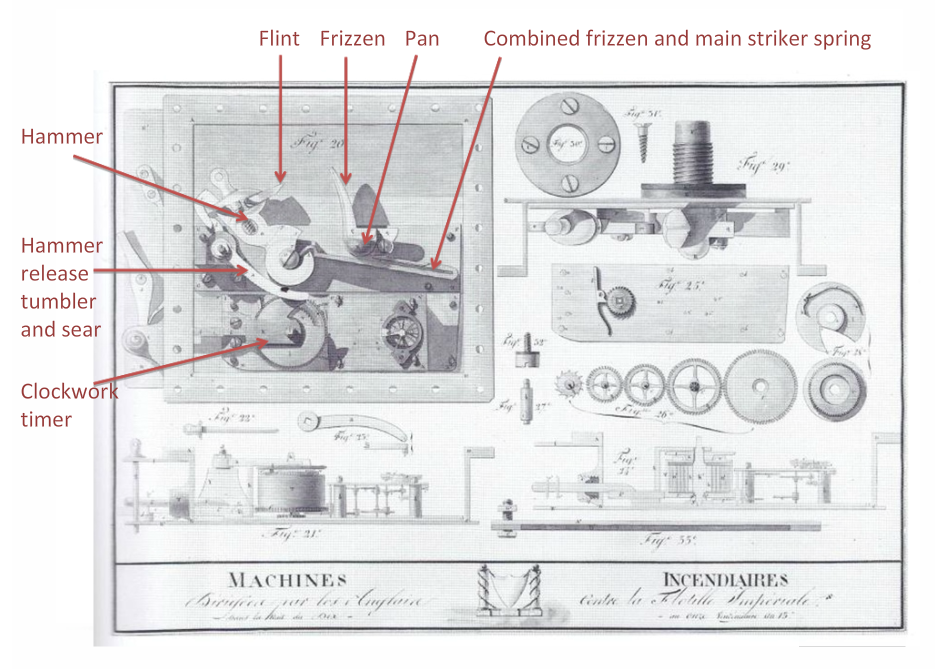

In 1805 Robert Fulton, an American working for the British Navy, (after being rejected by the French) designed a range of explosive devices using gun lock initiators. This diagram, produced by French technical investigators who captured and defused at least one of the devices following an attack on St Malo, shows clearly the firing lock mechanism adapted by Fulton as the explosive initiator. This diagram is one of my best finds. This is a very sophisticated device and a very sophisticated technical exploitation of the device by the French. The red annotations are mine, part of a lecture I give on historical technical exploitation.

In 1812, during the war with the British, Robert Fulton (who switched sides again, back to his mother country) used gun locks in a number of attacks using explosive devices on the British. This attack on HMS Ramillies which was blockading American ports, used a very simple device, and nbot one of Fulton’s designs, but nonetheless used firing lock. It is described by Benjamin Lossing (thanks again to John Wideman for finding this)

In the hold of the schooner Eagle, John Scudder, junior, the originator of the plot placed ten kegs of gunpowder , with a quantity of sulphur mixed with it, in a strong cask, and surrounded it with huge stones and other missiles, which in the event of an explosion might inflict great injury. At the head of the casks, on the inside, were fixed two gun locks with cords fastened to their triggers at one end and two barrels of flour at the other end, s that when the flour should be removed the locks would be sprung, the powder ignited and the terrible mine exploded. Thus prepared, with a cargo of flour and naval stores over the concealed mine, the Eagle sailed … . she was captured as expected and desired by armed men sent out on boats from the Ramillies. The crew of the Eagle escaped to the shore at Millstone Point, and anxiously awaited the result. The wind had fallen and for two hours unavailing efforts were made to get the Eagle alongside the Ramillies for the purposes of transferring the cargo to that vessel. Finally boats were sent out as lighters, the hatches of the Eagle were opened and when the first barrel of flour was removed the explosion took place. A column of fire shot up into the air a full nine hundred feet and a shower of pitch and tar fell upon the deck of the Ramillies . The schooner, and the first Lieutenant and ten men from the flag-ship on board of her , were blown into atoms and most of those in the boats outside were seriously and some fatally wounded.

Although not involving flintlocks I have details of Fenian IEDs using high explosive initiated by pistols connected to timers in the 1870s, and Lawrence of Arabia’s railway IEDs in WW1 were initiated by adapted martini rifles firing mechanisms – which themselves were an idea copied from the Boers in South Africa in the Boer war. However all these latter devices were in one sense different – they each actually fired a bullet into high explosive rather than igniting low explosive gunpowder.

I am by no means saying that every IED between 1540 and WW1 used gun locks – but gun locks enabled a simple and reliable way of initiating explosive charges and were used frequently and quite widely during the period. A gunlock could be used easily to initiate a device, by those three key ways – by command, by the victim or by timer. A gunlock enables concealment and surprise. I think these facts are crucial to an understanding of how IEDs were used in history.