UPDATE!!!

This story below, based on contemporaneous news reports, turns out to be incorrect. I’m indebted to JB for sending me the Irish History statement of an IRA member of the time describing how the tracks were manually removed causing the train to derail and crash. So the story below doesn’t stand up. But I’ll leave it here because its interesting on a number of levels:

a. how the press reports will vary from the truth quite dramatically.

b. The geography of the area that I assessed as being useful for a command-wire attack, also enable this manual sabotage operation.

Here’s what I wrote originally:

During the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s South Armagh in Northern Ireland was a tricky place for IEDs. Only the best and most experienced EOD teams were deployed there. And one particular part of South Armagh posed more problems than most and that was the railway line that snaked sinuously through the countryside. As the line gets towards the border, it can be viewed as if in a large amphitheatre, and can be observed for miles, and with the border close by providing escape routes, things were pretty challenging. At the time no-one told us this place had history. But exactly 100 years ago there was a very significant attack on the British Army here, blowing a train of the track and killing soldiers and horses. Here’s a brief outline.

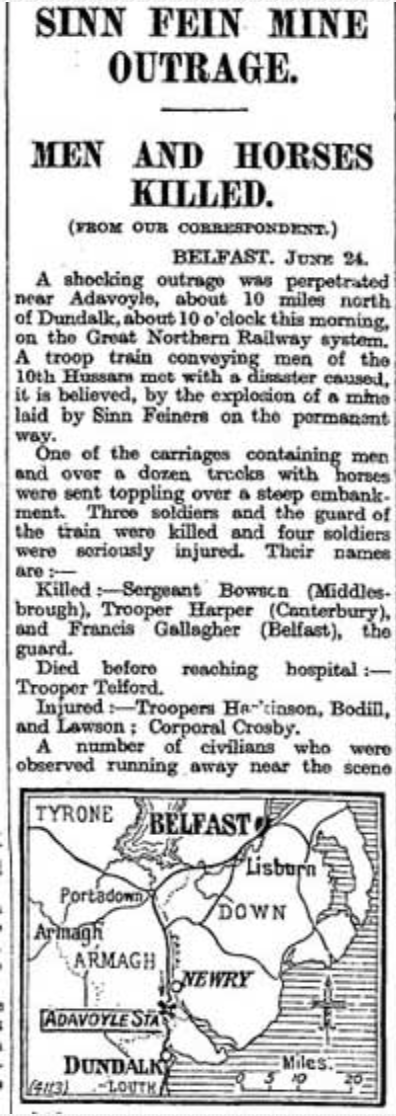

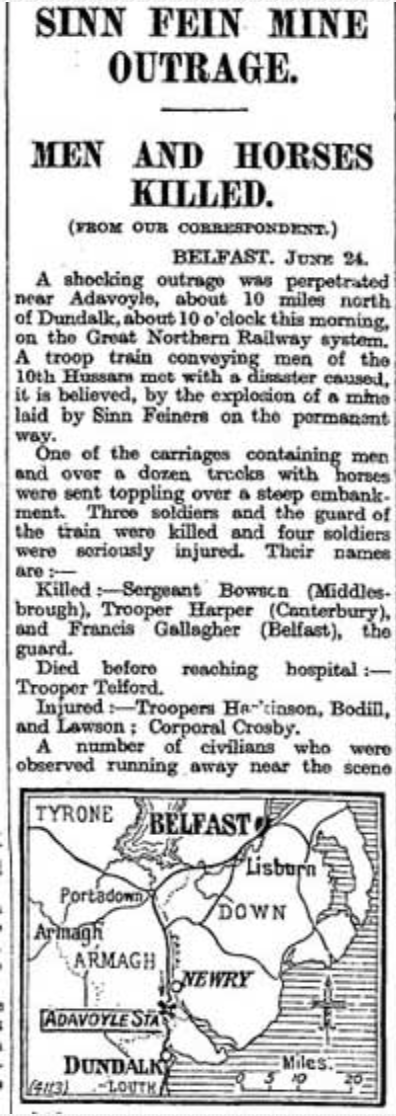

The new government in Belfast had just been formed. A British Army Cavalry unit, the 10th Hussars, normally based in Dublin, had travelled North by rail , in three separate trains with their horses, for the parades and pageantry associated with the opening of the new Ulster parliament by the king. On 24 June 1921, the unit were travelling back to Dublin again by three trains. It was the third and last train that was attacked. The front carriages contained the soldiers and the rear carriages the horses. A few mile beyond Newry the line runs through open countryside with Slieve Gullion on the right and the Ravensdale hills on the left. In the 80s and 90’s I knew this place as the “Drumintee Bowl” and in those days it was under a lot of observation from the British Army. In 1921 though it was just pretty rolling wild countryside. Both then, and in the 70’s,80’s and 90’s the place provides an “arena” for the IED – long views, little high hedged lanes, and a border to escape across. Tricky place for an EOD team, who can feel very exposed there. A lot of detailed procedural techniques were honed and carefully applied during EOD operations in the Drumintee bowl and on the railway line in particular.

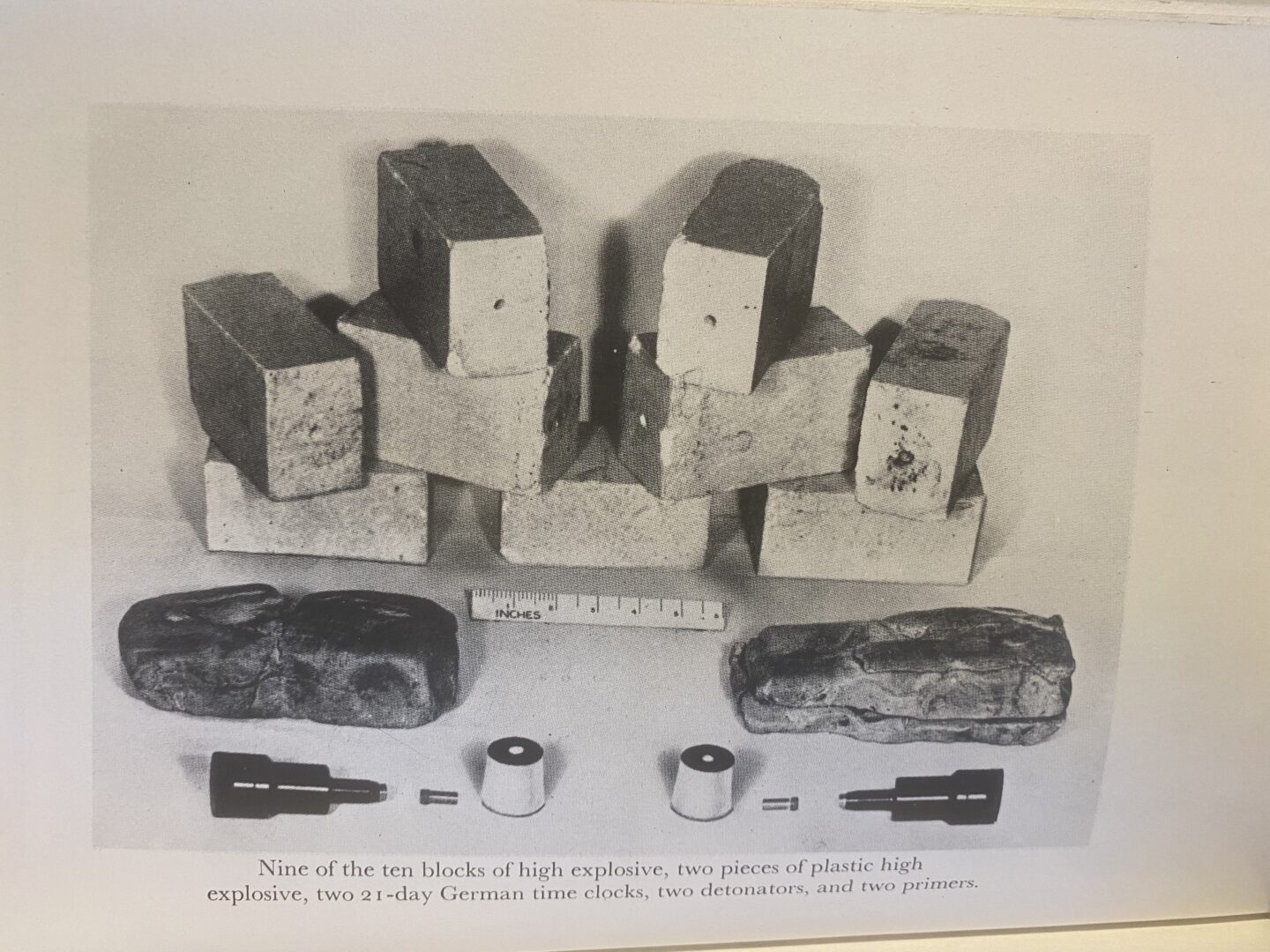

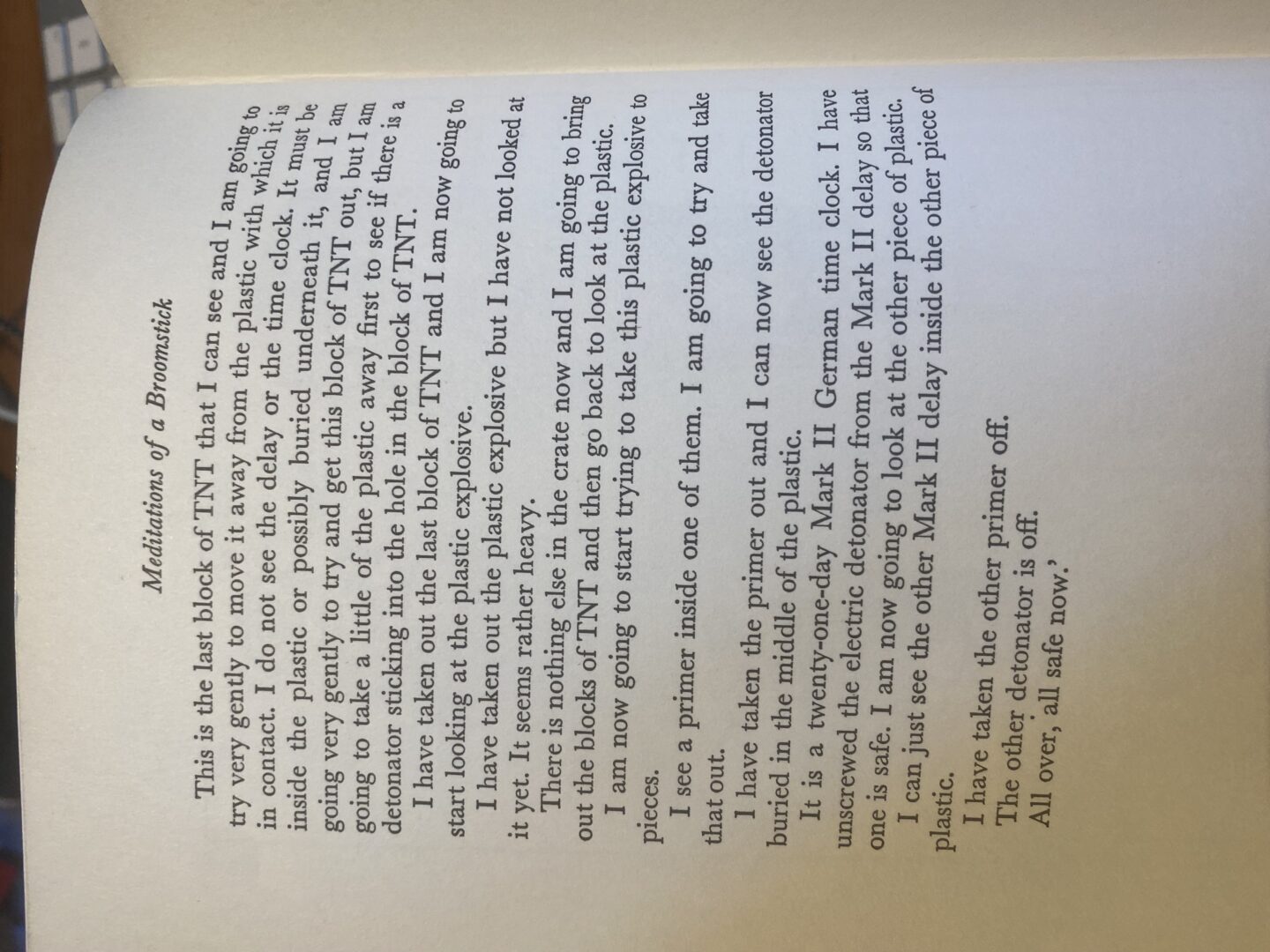

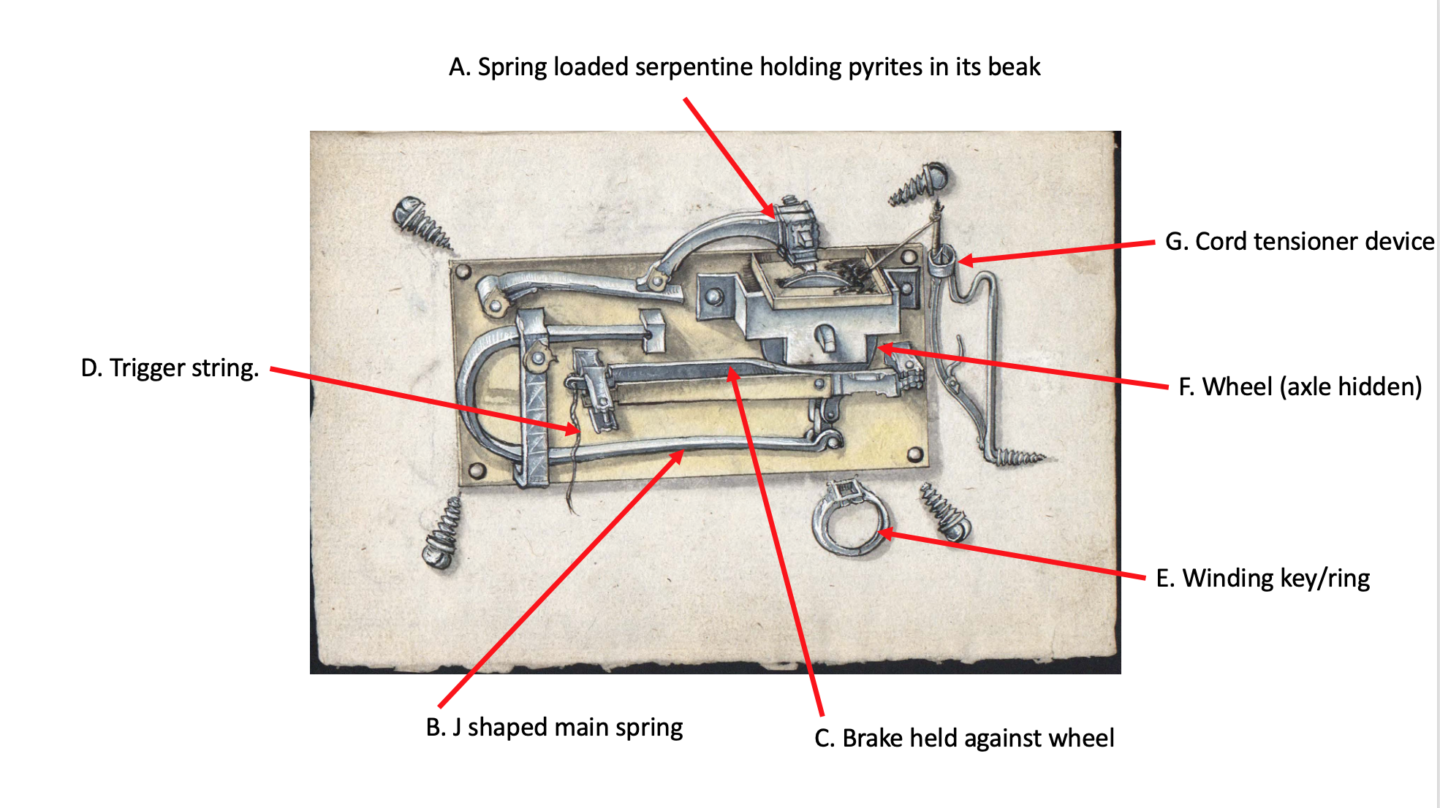

The railway line, which still runs today on the same route runs along an embankment, sitting about 7 -10m high, in full view. The IRA of the time, knowing the trains were to return to Dublin and knowing , presumably when the trains were loaded and boarded at Belfast, had planted two explosive charges under the rails. The press of the time suggested the device had a time fuse, but I think this is unlikely. Much more likely would have been a command wire, run to an observation point a couple of hundred yards away. Local IRA men had been trained in the use of electrical command -wire IEDs from the previous year and were equipped with the components including coil exploders.

As the train passed the point of explosion, the circuit was made and the device exploded under about a midpoint on the train. One carriage containing a few soldiers took the brunt of the explosion and three of the soldiers were killed. The carriages behind containing the horses then tumbled off the embankment and about 50 horses were killed (all but one). Here’s a Pathe news reel of the time at this link.

Of course it’s no surprise that the characteristics that made this place attractive to the bombers of 1921 were the same 60 years later. The IRA probably knew fully well about the 1921 attack – I can tell you that the EOD teams operating in South Armagh 60 years later were , to their chagrin, less aware of history than they should have been. Other attacks planned by the IRA in the 1920/21 era in South Armagh included pumping oil and paraffin in a mix into a police Baracks in Camlough as a pumped “flame thrower” incendiary. This technique was returned to by the Provisional IRA to attack the RUC station in Crossmaglen in 1993. (Guess what, the British Army had forgotten the earlier attack) , and using a large explosive device paced at the entrances to police barracks – another techniques which came around again in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s in that same place.

The soldiers who died that day in 1921 were Private Carl Horace Harper, Private William Henry Telford and Sgt Charles Dowson.

The attack was carried out by a IRA unit led by Frank Aiken, a notorious man who commanded the IRA volunteers of South Armagh and Newry at the time. In the weeks that followed their were tit for tat reprisals including the shooting of four IRA men by the B Specials, and so on. South Armagh always was a hard place.